Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

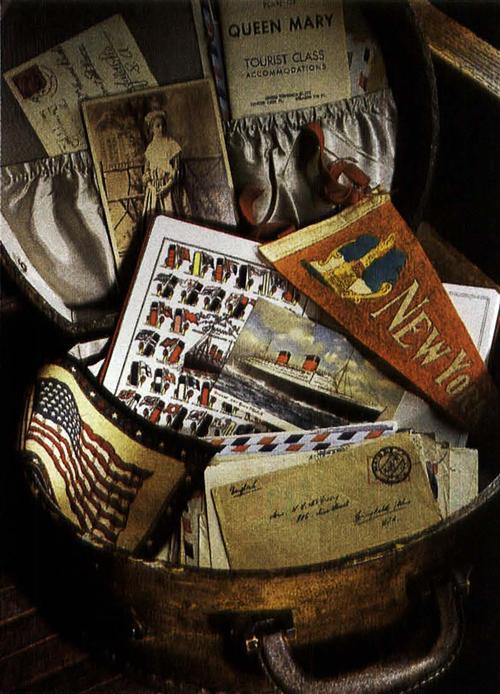

I’m out of luck, but you may have family history treasures right under your roof. Sometimes, it’s the clues in an old, tucked-away letter, an inscription on a pewter plate or a date on a certificate of citizenship that will be the key to opening the genealogical gates. Even if, like me, you discover that your genealogical treasure chest doesn’t contain family jewels, there’s still hope of recovering some of the lost gems.

You’ve probably read the advice dozens of times, including in the pages of this very magazine: Start with “home sources.” But what does that really mean? It’s simple: After writing down what you know about your family history from your own personal knowledge, the next step is to look for things around your home that may fill in some blanks on your charts. Remember: the rule of genealogical research is to start with yourself (the known) and work backward in time to your parents, grandparents and so on (the unknown). If you haven’t done so, use charts and forms like those you can download free at <www.familytreemagazine.com/freeforms> and begin filling in the data you know.

The scavenger hunt begins

Think of looking for home sources as a genealogical scavenger hunt. All these family history items give information about you, your children, your parents or other relatives — how many can you find?

- birth certificates and baby books

- baptism and confirmation certificates

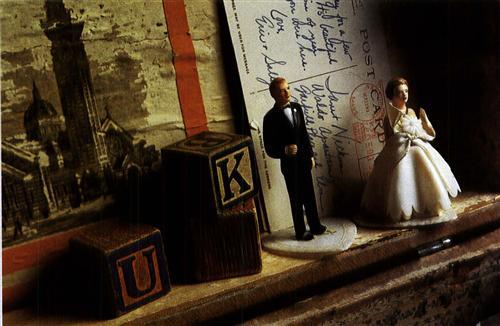

- marriage certificates and wedding albums

- death records, prayer or funeral cards

- school report cards and yearbooks

- scrapbooks

- house deeds and photographs

- checkbooks and bank statements

- citizenship papers and passports

- military discharge documents and medals of honor

- family Bible

- letters, postcards and telegrams

- diaries and journals

- wills and estate papers

- medical records

- newspaper clippings

- recipe books

- photographs

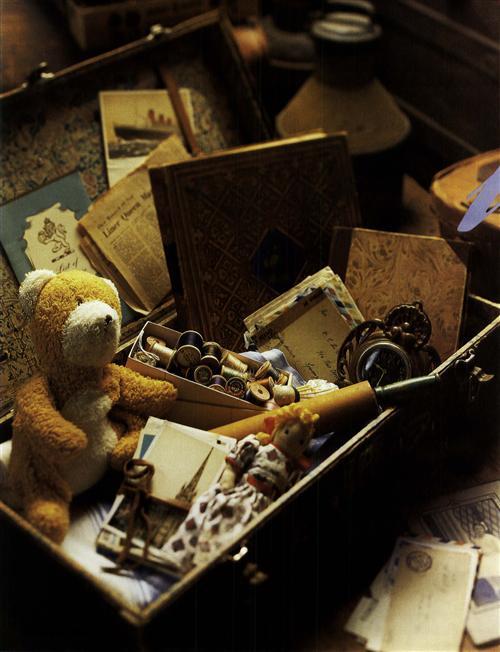

Hunt for artifacts and heirlooms that may give you genealogical clues or tell you about a person’s life. For a guide to identifying and interpreting family treasures from the PBS hit series “Antiques Roadshow,” check out Antiques Roadshow Primer by Carol Prisant (Workman Publishing). But first, you have to find those valuable heirlooms. Here are some items to look for:

- needlework, quilts: Did the artisan stitch initials, a date or the name of a location on the object?

- dishes, china, silverware, pewter items: Do the pieces have any markings that reveal the maker or date?

- weapons, such as knives, guns, swords: Can you date these items by matching them to antique catalogs or online sources? Do they have any engravings on them?

- clothing, shoes, hats: Look for reproductions of or historical catalogs on antique clothing to date these items.

- jewelry: Has it been inscribed with initials and dates? Can you date the piece from books, online sites or antique jewelry catalogs?

- books, magazines: These reveal your relatives’ and ancestors’ personalities.

- knickknacks, souvenirs: Where did they come from? Can you determine their age and identity?

- toys, games: Research books and catalogs about antique toys and games.

- furniture: Did the maker carve initials on a piece of furniture?

- collectibles, such as coins, stamps, bottle tops, baseball cards, political buttons: These items can reveal much about an ancestor’s personality and possibly divulge political views.

- musical instruments: Can you determine when the instrument was made? Who in your family owned and played it?

- tools, kitchen items, household devices and farming equipment: Can you identify tools and devices through reference books or catalogs?

Thoroughly examine everything you find for genealogical information or clues. Let’s look at a few examples.

It’s a girl! Or is it?

Although you know your own birth date, can you prove it? Sure, you were there, but you have to depend on others for the details. Look for your own birth certificate, then study it. Many people have been surprised to find that they were recorded with no name other than “baby” or accidentally listed as the wrong gender. Do the date and place match what you’ve recorded on your charts? Does the certificate give your mother’s maiden name or your father’s occupation?

In your genealogy charts or software, cite your birth record as your source of information for your birth date and place, and the names of your parents. If you find discrepancies, note this on your charts — just because it’s an official document doesn’t mean it’s 100 percent accurate. Your birth certificate connects one generation to the next; it connects you to your parents.

Say cheese!

Many articles in past issues of Family Tree Magazine have covered family photographs, with advice from Maureen A. Taylor, author of two guidebooks on the topic: Preserving Your Family Photographs and Uncovering Your Ancestry through Family Photographs (Betterway Books). But let’s review a few basics since family photos are among the most common genealogy finds in your household search.

In a perfect world, all photographs would list on the back the full names of all the people in the picture, the place where the picture was taken and the date it was taken. Alas, most of our ancestral photo finds are all too imperfect. If you have old family photographs, do your best to identify them and preserve them properly for future genealogists, using the guidelines in Taylor’s books.

Sometimes, you can identify cousin Mary in a photo from looking at other photos that you know are of cousin Mary. Sometimes, you can pinpoint the time period when a photo was taken by the clothing the people were wearing. If the photo was taken outside, you can guess an approximate time of year based on the seasonal appearance of the trees and shrubs. You might even be able to date the photograph just by identifying what type of image it is, such as a daguerreotype, tintype, ambrotype, carte de visite, cabinet card, glass-plate negative or cyanotype. Daguerreotypes, for example, were popular from 1839 to 1857, tintypes from 1856 to 1938. Again, Taylor’s books will help you analyze and identify the type of photograph you have.

Bring pictures with you when you visit relatives to conduct oral history interviews, and ask relatives to show you their photo collections. Perhaps they’ll be able to help you identify people, and maybe they’ll even loan you their pictures so you can have copies made.

Scrapbook secrets

Just as scrapbooking is a popular pastime now, it was also a favorite hobby for many of our grandmothers and great-grandmothers — and even some of our grandfathers. Your home search may turn up a scrapbook containing fashions clipped from magazines, newspaper clippings, locks of hair, invitations to parties and other items the scrapbooker held dear.

Along with possibly giving you genealogical clues, scrapbooks offer a glimpse of the owner’s personality. One of the most interesting scrapbooks I’ve come across was one a man kept of his college years at Princeton. In it, he kept programs from school plays, political buttons, score-cards from football and baseball games, his dance cards, programs from school events and even a signed pledge with his friends that they would quit smoking. Think of scrapbooks as visual diaries of a person’s life or a time period in a person’s life.

Dear Uncle Knickknack

Among the real treasures you may uncover in your hunt are old letters, which can be rich in family history information as well as gossip. Letter writers often tell what’s happening at home and discuss people the recipient knows. Before telephones, this was the main means of communication among family members. You may even find that one of your ancestors was a genealogist and got the search started for you:

Feb. 5, 1901

Dear Papa,

I received your letter yesterday and was disappointed, but not surprised to find that you had taken no steps to procure the desired information that lies within your grasp. All of the old FitzHughs lived, and most of them died, in Stafford and Westmoreland counties, where their wills, their deed[s], and their marriage licenses must be on record in the clerk’s offices of those counties, or in that of King George Co. which was formerly a part of those counties. A little exertion on your part in this matter would be rewarded by a world of information and enable us to process, once and for all, a correct record of our family.

Your loving son,

Horace A. FitzHugh

You may hit a gold mine if you uncover both the sender’s and the receiver’s letters. I worked on a project where a couple had saved the letters they’d written each other while they were separated during World War I. Putting their letters together gave me the whole picture of the man’s war experiences and what his fiancee was doing at home while he was in France.

If you have a whole cache of letters, besides preserving the originals, you may want to photocopy them to share with relatives or publish them. I published the collection of letters. With some additional research and material, they made a nice biography of the couple, which I titled A Sense of Duty: The Life and Times of Jay Roscoe Rhoads and His Wife, Mary Grace Rudolph (Newbury Street Press). You can do the same. Katherine Scott Sturdevant’s Organizing and Preserving Your Heirloom Documents (Betterway Books) is a guide to preparing and annotating family letters for publication. Publishing your ancestors’ letters, diaries and daybooks is not only an excellent way of preserving them, but also a lasting legacy and tribute.

Tales of treasure

While some home sources, such as birth certificates and other official documents, may be self-explanatory, others might not be so obvious in their meaning. My most treasured family heirlooms are dishes — not even a complete set — that I inherited from my grandmother. But after my demise, will my family know the importance of this odd assortment of china? Or will they sell my precious family treasures at a garage sale?

To ensure such items are kept in the family, it may not be enough — or even feasible if you have many items — to mention them in your will. Instead, attach a note to each family heirloom, giving its history and noting whom you want to receive it after you’re gone. Consider making an inventory of your home sources, complete with a history of each item: how it came into your possession, who owned it originally, the date of the item and any family stories associated with the heirloom.

Coming up empty

Don’t worry if your scavenger hunt isn’t as fruitful as you’d hoped. I was in the same boat. My family kept little, so I had to hunt and gather elsewhere — my relatives’ homes. Of course, it’s always much nicer if you ask your relatives’ permission before you start rummaging through their closets, attics, trunks and drawers!

Anytime I visited relatives, I asked if they had any family history treasures. You might even bring along the list in this article to help jog relatives’ memories. Although you may try your hardest to convince them that you really should be the keeper of that great Civil War sword or those World War I letters, family members may be reluctant to turn over these treasures to you. Instead, start an inventory of where family artifacts and heirlooms are, listing the relative’s name, contact information, description of the item and the item’s history — who owned it originally, how it passed down in the family, how the original owner got it and so on. Also, take a photograph of the treasure from different angles and include this with your inventory. Here’s an example from a project I worked on for a family:

Dark blue Stafforshire tea and coffee set, ca. 1840. Set consists of a coffee pot, tea pot, creamer, sugar bowl and four cups and saucers. All but the sugar bowl and creamer, purchased at a later date, belonged to the family of Emma (Ludwig) Rhoads and were used at their farm at Yellow House, Pennsylvania.

I also recorded the name and address of the present owner. Take note of heirlooms that may have been in the family but are no longer in the family’s possession. Try to get a complete description:

Unfinished and unsigned sampler, probably stitched by Ellen M. Lorah, daughter of Mary (Rhoads) Lorah, Broomfieldville, Berks Co., Pennsylvania, who attended the Linden Hall School for Girls in Lititz, Pennsylvania, in 1866, when she was 16. Floral decorated, about 6″× l8″. Current owner: unknown.

Keep your family history inventory and photographs of items in your genealogical files. Store important papers in a safety-deposit box to ensure heirlooms stay in the family. You might also post the inventory on your family history Web site (see page 54), especially if you have many unidentified items or you don’t know the whereabouts of some lost items.

Looking through the haystack

Maybe your home sources didn’t end up in a relative’s home. Maybe throughout the years your family photographs, documents and artifacts — if they survived — somehow made their way into a repository, museum, antiques store or private hands. How on earth will you ever find them? While it might seem as though you’re looking for a needle in a haystack, some places and sources are easy to check.

• For loose papers, documents, diaries, letters and the like, check the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections (NUCMC), published annually since 1959 by the Library of Congress. Repositories all over the country report their manuscript holdings to the Library of Congress. You’ll find NUCMC in reference sections of academic libraries and in large public libraries; some years are online at <www.loc.gov/coll/nucmc/nucmc.html>. A two-volume set called Index to Personal Names in the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections 1959-1984 is especially helpful.

• Check genealogical and historical societies in the places where your ancestors lived and died.

• For artifacts, check with the museums and antiques stores in the areas where your ancestors lived and died. Ask if they received any donations of your family’s treasures, or if they bought any at auction. Give the names, birth and death dates, and time period when your ancestor lived there.

• Place queries in local genealogical publications and online in hopes of contacting distant cousins who may have inherited family items.

• Check eBay <www.ebay.com>. If a family item that has monetary value has fallen out of family hands, the owner may auction it online. Even heirlooms that don’t fetch a lot of money — think family Bibles — are offered for sale on the Internet.

It saddens me to say that I don’t have that Hershey-candy-bar love note my father wrote or cousin Henry’s diary or Grandmother’s Singer sewing machine. I’ve managed to recover some genealogical treasures, however. Throughout the years, I’ve been able to photograph — and sometimes even inherit — other precious items that were hidden away in relatives’ homes.

ADVERTISEMENT