Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

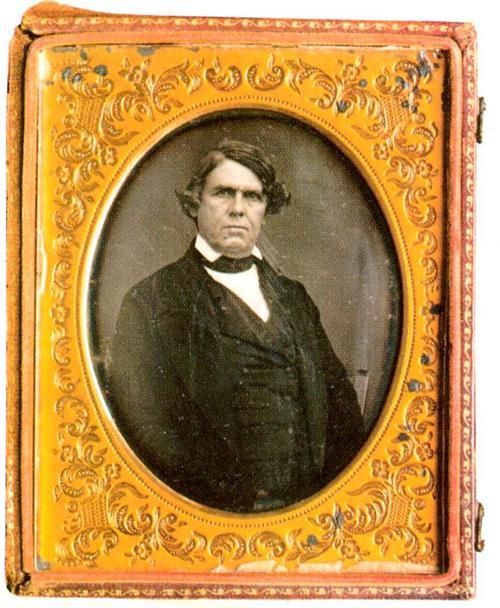

Cased images like the one shown on this page are among photography’s earliest — and, to many, most interesting — images. But to the family historian playing “photo detective” in search of clues about your past, these can be among the most puzzling images to try to make sense of. For one thing, their sheer age makes their mysteries more challenging to unravel. For another, they simply don’t look and feel like the snapshots that we’re used to. They’re not even on paper — they’re on metal or glass.

Ironically, though, paper of an entirely different sort can help you solve these old photo riddles: old newspapers. Let’s see how newspapers can be a source of clues, using the example pictured here.

What’s your type? ¦ Photographs in cases fall into one of three types, depending on their age and the technology used:

• Daguerreotypes, used from 1839 to about 1855, were a direct positive image on silver-plated copper.

• Ambrotypes, used from 1854 to about 1870, were imitation daguerreotypes on glass rather than metal. Actually a negative image, an ambrotype was made to look like a positive with a dark backing; shadows, being clear, let the dark backing show through. Other parts of the image look grayish-white.

• Tintypes, from 1854 to about 1900, were also called ferrotypes because of the thin, enameled black iron plates (not really tin) they were made on. Like an ambrotype, a tintype created a “positive” image by use of a dark background.

I easily identified this photo as a daguerreotype by the mirror reflection when I shift the image back and forth in my hand.

Steamboat’s a-comin’! ¦ The information accompanying this photo gave me a huge head start in learning the story behind this particular daguerrotype. The subject’s name is noted as “Philip Pennywit” and his occupation is listed as “steamboat captain.” But who was Philip Pennywit and where did he ply his trade?

For answers, I turned to old newspapers. As steamboats provided more goods at lower costs, early papers followed the arrivals and departures of the boats and their cargoes in great detail. Through the Arkansas Gazette, I discovered that in 1828-29 Pennywit’s steamboat Facility plied the river between New Orleans and Little Rock. On one trip he continued up the Arkansas to Cantonment Gibson, delivered emigrating Creek Indians, then picked up cotton, hides, furs and pecans for his return trip. After a successful time on the Arkansas, the Facility returned to the Mississippi. In December 1829, Pennywit captained the Waverly, later the first boat to travel the White River in January 1831.

The Arkansas Gazette on Dec. 1, 1829, commented not only on Pennywit’s vessel, “a fine staunch boat, with elegant accommodations for passengers,” but also on the man himself. According to the newspaper, Pennywit’s “gentlemanly deportment and obliging manners entitle him to a liberal patronage.” (If the good captain were your ancestor, wouldn’t this be a wonderful find?)

Pennywit’s 1868 obituary added that the captain’s steamboating career began at Cincinnati, where he reportedly built the city’s first steamboat — the Cincinnati — in 1818. And though Pennywit retired from the steamboating profession in 1847 to pursue various “mercantile and manufacturing businesses,” thanks to local newspapers of the era we know that “his name is inseparably interwoven with the history of navigation on the Ohio, Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers.”

Try matching your own cased images to newspaper archives. You may discover the stories behind these old faces on metal and glass.

From the June 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT