Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

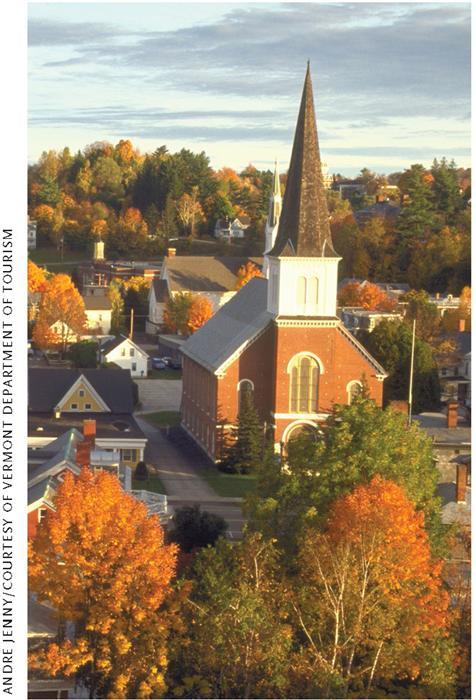

Vermont is known for brilliant fall foliage, snow-covered slopes and cow-dotted pastures, but there’s more to the Green Mountain State than bucolic beauty. Genealogy resources, for example, areas thick as its pine forests. But if you’re hoping to find your family here, you’ll need a healthy respect for the role of geography and climate in state history. Harsh winters and high elevations discouraged people from moving in. Even today, traversing the second-least-populous state from its Canadian border to the southern foothills involves dodging mountains. Of course, you’ll want to see the Green Mountain State’s loveliness in person-but with our research tips, you won’t have to scale mountains to climb your Vermont family tree.

Old as the hills

As the first state to grant voting rights to all men regardless of race and to abolish land-ownership requirements, the Green Mountain State is known for its political independence. During the 17th century, the established colonies of New York and New Hampshire both awarded land grants in wide-open Vermont. New York, meanwhile, ignored the state boundary at the Connecticut River. Continuing land disputes led Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys to try to drive out New Yorkers and, in 1777, declare Vermont an independent republic. It became the 14th state in 1791, with Montpelier as its capital.

To avoid the mountains, many migrants seeking agricultural opportunities traveled up the Connecticut River from that waterway’s namesake state. But Vermont’s brutal winters and a depressed economy sent them to kinder environments: During the 1820s, approximately half the state’s population left many for New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin, as well as Lower Canada (the British colony that covered what’s now southern Quebec and the Labrador region). Out-migration was such a problem that a few towns even changed their names to sound warmer: Bromley, for example, became Peru.

During the late 19th century, the Yankees who left Vermont were replaced as newcomers from Quebec and Scotland arrived to farm and work stone from the state’s plentiful quarries. Irish immigrants built canals, including the 1823 Champlain Canal.

French Canadians came, too, to work in mills and operate abandoned farms. Today, their descendants makeup more than 20 percent of Vermont’s population. Track their immigration routes in the St. Albans lists of border crossings from 1895 to 1954. They’re available on microfilm at National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> facilities and the Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org>, as well as through Ancestry.com’s <Ancestry.com > US Records collection ($155.40 per year). Learn more about researching French Canadian ancestors in the June 2006 Family Tree Magazine.

Mountains of resources

The following records will figure prominently into your Vermont research:

• Vital: Your ancestor’s town name is important because the majority of Vermont records are kept at the town level. Although most town clerks ignored a 1779 vital records law, some records prior to 1820 list births (with birth place) and deaths of whole families. Statewide civil registration officially began in 1857, when the state required town clerks to forward birth, marriage and death information.

In 1919, legislation gave the state power to get copies of vital records from towns and churches. Communities with incomplete pre-1870 death records had to compile the data from gravestone inscriptions. The information is recorded on index cards, which you can access on microfilm at the Vital Public Records Division of the General Services Administration in Middlesex, Vt., and at the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) <www.newenglandancestors.org> in Boston. Some transcriptions of early vital records are available online to NEHGS members.

The FHL has microfilmed indexes to vital records from the Colonial era through 1954-rent them through an FHL branch Family History Center, which you can find using Family Search. Records older than five years are available from the Vermont Public Records Division (see resources). Look for vital records at the town level, too, in case your ancestor’s information wasn’t sent to the state.

• Church: Use membership lists, baptisms, marriages, deaths and removals (lists of parishioners who transferred to other churches) to trace Vermont families before civil registration. Start with the Vermont Historical Society’s (VHS) <vermonthistory.org> Vermont Historical Records Survey collection of town and church record inventories. Click the Manuscripts link on the left side of the Web site and search on the collection name to access its finding aid.

You can find cemeteries using the maps in Burial Grounds in Vermont, 4th edition, edited by Arthur L. and Frances P. Hyde (Vermont Old Cemetery Association). Look for published indexes in the bibliography Known Cemetery Known Cemetery Listings in Vermont, 4th edition, by Joann H. Nichols, Patricia L. Haslam and Robert M. Murphy (VHS).

• Land: Those Colonial disputes mean early land transactions may be recorded in New York, New Hampshire or Vermont. Run a vermont place search of the FHL’s online catalog and look for a land records heading to find microfilmed land claims from these states. Land records after Vermont became a republic are in town clerks’ offices; most are on microfilm at state repositories such as VHS (there’s no statewide index). Look for names of individuals issued land grants from 1763 to 1803 in Jay Mack Holbrook’s microfiche Vermont’s First Settlers (Holbrook Research Institute).

• Court: To find probate documents, you’ll need the name of the probate district, not the county. Use a reference such as Red Book, 3rd edition, by Alice Eichholz (Ancestry) to find it. Records up to 1850 (and a few to 1900) are on microfilm and indexed at the Vermont Public Records Division and the NEHGS library. The indexes also are available at the FHL. Since the microfilms don’t include all the papers in a probate file, you’ll want to track down the originals. There was no effort to microfilm post-1850 court records, so seek originals at the court’s district office. District courts often have card indexes focusing on estates and guardianships, too.

• Census: Jay Mack Holbrook compiled an early enumeration of sorts from land grants and other sources in 1771 Census (Holbrook Research). Use his citations to find the original sources and verify whether your ancestor actually lived in Vermont or was just awarded land there.

Vermont just missed the first federal census in 1790, but the government counted residents when they ratified the US constitution in 1791. That head count is part of the 1790 federal census records, which you can access in Ancestry.com databases, through libraries that subscribe to HeritageQuest Online, and on microfilm at NARA. You also can see that 1791 census data in the two-volume Vermont Families in 1791 edited by Scott A. Bartley (Genealogical Society of Vermont).

• Military: Unfortunately, a fire destroyed most of Vermont’s original military service records predating 1920; the state public records office has the remnants. Miscellaneous records are in town clerks’ offices and at the state archives. For example, you’ll find the Adjutant General’s Office lists of people who served in the Revolution through Desert Storm at the archives, VHS and other major libraries (contact VHS staff to request a lookup). VHS also keeps an index to graves of veterans from the Civil War through World War II.

• Newspapers: These are especially useful for ancestors who predate statehood-era records. The Vermont Department of Libraries <dol.state.vt.us> catalogs an extensive collection of papers dating back to 1781. View microfilmed papers there, or search the catalog and note names of repositories holding papers of interest. You’ll find library contact information on the site.

Easy climb

Identity family documents in the VHS library in Barre and other repositories using ArcCat <arccat.uvm.edu>, an online cataloe of manuscrint collections in several libraries. You can search on a keyword (such as your family name), author or title.

Thankfully, VHS, which has Vermont’s largest genealogy library, mostly eliminates the need to travel the state’s rough terrain in search of records, family history books, manuscripts and photographs. The library’s helpful staff chases a way Vermont’s winter chills, and you’ll find similar charm in the small towns tucked into Vermont’s hills and valleys. The creased landscape nurtured your ancestors, a rugged people used to the adversity of long winters and hard-to-till soil. What’s a little genealogical toil compared to that?

ADVERTISEMENT