Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

While doing genealogical research on my family in the 1990s, I learned that my grandmother, Emily (Reese) Kidder, was an “orphan train” rider. During her lifetime, she would often speak of being an orphan in a Brooklyn, NY, orphanage, and how she was brought west on a train by a Seventh-Day Baptist minister named H.D. Clarke. It wasn’t until much later, when I received a flyer from the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America that I began to piece the puzzle together. Unfortunately, my grandmother died in 1986, prior to my realization that she was a part of something so big.

Are you one of the estimated 2 million individuals who descend from what are now referred to as orphan train riders? Between 1854 and 1929, some 150,000 youngsters, from babies to age 14, and even a few adults, were part of a program known as “placing out.” These children were sent away from the cities and into the country to be placed in foster homes. Once referred to as “baby trains” and “mercy trains,” this system is now known as the “orphan trains.”

I’ve since learned that my grandmother was not an orphan at all, but was simply abandoned by her parents, who had recently separated. She and her older brother Richard came into the care of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in 1900. They were soon transferred to an orphanage called the Home for Destitute Children in Brooklyn, where Richard was quickly adopted. Emily was to spend six long years of her life at the orphanage. In 1906, Emily was transferred to the Elizabeth Home for Girls, which was a reform school for so-called “incorrigible girls.” She was briefly placed with a woman “for training,” and then came into the custody of the Children’s Aid Society. On March 13, 1906, she was loaded on an orphan train bound for Hopkinton, Iowa. The Rev. H.D. Clarke was acting as the placing agent.

Entering the System

The program known as “placing out” began with the Children’s Aid Society of New York City, founded by Charles Loring Brace. In the latter part of the 19th century, many organizations followed the society’s lead and ran their own orphan placement programs. Each agency adopted its own policies, but in all cases, trains were used to transport the children to their new foster homes. Nearly every state received these children, with the emphasis on states in the Midwest. Typically, groups of six to more than 100 were rounded up from the streets and orphanages of the big cities and bathed, fitted with a new pair of clothes, perhaps given a Bible, and then sent on the trains to be placed with families.

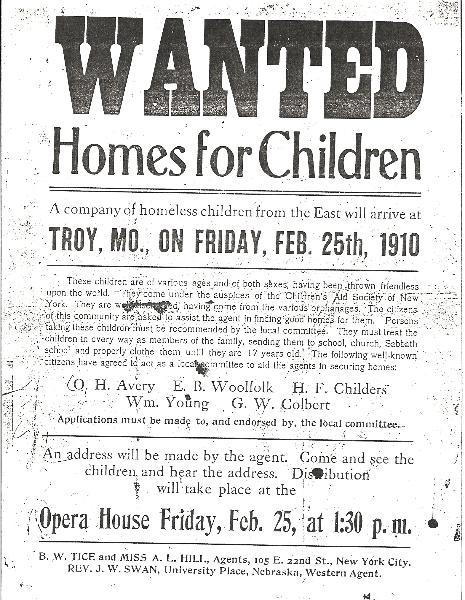

In the case of the Children’s Aid Society, advertisements were placed in local newspapers at the destinations (see example above), and a local committee was established approximately two weeks prior to the arrival of the train. Prospective foster parents would come from as far as 30 miles away to take their pick of a new son or daughter. The society discouraged the placements of siblings in the same household, as they feared their feuding would just give foster parents another excuse to have them removed. The children would be lined up on the steps of the courthouse or the stage of an opera house. Often, the children would sing or dance, or otherwise perform for the audience. At the end of a speech by the placing agent, the children would be inspected (not unlike cattle) by the prospective foster parents. The placing agent would then inspect the homes of the foster parents within a few days after the placement, and follow up with yearly visits, or more often if conditions called for it.

If lucky, the new foster children would find good homes, but quite often they were simply used as maids and farmhands, and would need to be placed in numerous homes until a suitable one could be found. If the agent didn’t arrive in a timely manner to remove a child, the child might run away to escape abuse. As Clarke once said, “An orphan’s faults are magnified above others.” He recorded one case where a child was cast away from his foster home for dipping his finger in the peanut butter jar. Another child was sent away for “swatting too many flies,” and therefore displaying too much aggression.

Often, bizarre requests were made when applying for children. Clarke recalled one such request: “Mr. Clarke, I want a little girl with curly black hair and black eyes, pleasant features, good form, a good singer and a good memory, so as to take part in Sunday school concerts, and a complexion that will not tan or freckle in the sun.”

In the case of the New York Foundling Hospital, foster parents would be identified prior to sending the children on the train. Each child was assigned a number, and the name of the new foster parents would be sewn into his or her collar. Generally, the Children’s Ad Society placed Protestant children in Protestant homes, and the Foundling Hospital placed Catholic children in Catholic homes, though there were many exceptions.

Finding Permanent Records

The term “orphan train” is a bit misleading, as the greater percentage of the children sent on the orphan trains were not true orphans. In many cases, one or both parents were still alive but unable to care for their children for reasons such as spousal desertion, poverty, destitution and neglect. Many of the children were considered juvenile delinquents, but in those days, a child could be considered a delinquent for smoking a cigarette, being homeless or simply keeping bad company. One of the great tragedies of the orphan trains is that, at least in the case of the Children’s Aid Society, the children were not allowed to have any further contact with family or friends they had left behind.

Researching an orphan train rider can pose special problems, but you can reap many rewards as well. Nearly all of the orphanages that existed in those days are now gone. However, the Children’s Aid Society and the New York Foundling Hospital, among a few others, still operate. These two organizations have offices of closed records with staff members who will search for information about your family member. Be patient when making your request, as these places are overwhelmed with work and are often staffed with volunteers.

The Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, part of the National Orphan Train Complex, is a central repository for information on all known orphan train riders. Provide as much information as you possibly can when writing to these places. The Children’s Aid Society and the New York Foundling Hospital are quite protective of their records, and you must generally prove to them that you’re related to the person you’re researching. Even then, in most cases you will get a condensed version of what’s found in their files. Part of this is simply due to time restrictions. Visit in person if you can, for better results and more complete information.

The children generally retained their original birth names, but often the foster parents would simply “assign” a new first and last name. In the rare cases of actual adoption, the last name would certainly have been changed to that of the foster family’s. Such was the case with my grandmother’s brother, Richard: He was allowed to keep his first name, but took his adoptive parents’ last name.

The amount of information about these children you’ll find in institutional records varies widely. I made an exhaustive search for any existing records of the Home for Destitute Children, which housed my grandmother. I finally located them at Forestdale Inc. in New York, the contemporary version of the home. The Children’s Aid Society has some of the best records available, on the other hand. In 1999, I flew to New York and visited the society in person. To my amazement, they still had a plump file on my grandmother Emily, even including a letter she wrote to the society on Dec. 26,1906. (The society encouraged the children to write at least twice a year to report on their well-being and plans for the future.) The rest of my grandmother’s file consisted of various reports that the Rev. Clarke had sent regarding the foster homes that my grandmother was placed in.

The contents of this file were fascinating, yet painful to read. I learned that my grandmother was placed in no less than seven homes in seven years, in four states. Reasons for replacement included “not clothed properly,” “not sent to school for a year” and “deserted at a religious camp meeting in the woods of eastern Iowa.” One item in the file was a letter from a cousin searching for records on Emily. My newfound cousin filled in a lot of blanks on the family tree.

Adding Luck to Hard Work

I had the unique experience of discovering a new source of orphan train records in 1997. One of my aunt’s friends told her that she had some interesting records on my grandmother. My aunt quickly passed on the information to me, as she knew I was working on the family tree. To my amazement, the lady who held the records was none other than the widow of the Rev. H.D. Clarke’s grandson! Clarke had kept extensive records on many of the nearly 1,300 children he placed. He created seven hand-typed leather-bound volumes to present to each of his grandchildren, and to an adopted daughter. The grandson’s widow was in possession of only three. I quickly went on a hunt to find the remaining volumes, now scattered across the country in the homes of other descendants of the Rev. Clarke. I located all but one.

The journals and scrapbooks were filled with vivid descriptions of the children, as well as photos of many of them and transcripts of their letters. In addition, birth, marriage and death dates were included for a good number, as well as information on who took the children and how they made out in life. I knew the records and photographs needed to be preserved for posterity, so I gathered all the information together in a single book, Orphan Trains and Their Precious Cargo: The Life’s Work of Rev. H.D. Clarke (Heritage Books).

Combing Available Resources

When searching for records on an orphan train rider, you should always start with interviewing relatives first, and then move on to local, state and national record sources, in that order. Don’t overlook sources such as local genealogical societies, obituaries, and birth, marriage and death certificates when searching for clues.

Often, the local newspaper would write up a big story about the coming of the train and the placement of the children. The names and ages of the children, as well as the foster parents’ names, are sometimes listed, too. Newspapers are available on microfilm through interlibrary loan. Start with your local library, and it will in turn consult larger libraries or state historical societies for this microfilm. Or visit your state historical society in person. Call ahead to confirm that it has newspapers covering the time period and city in question. The state historical society of Wisconsin has one of the largest newspaper collections in the United States.

Other records of interest are indenture, adoption and baptism records. The New York Foundling Hospital had children baptized before sending them on the trains. The New York Juvenile Asylum (now called Children’s Village) demanded indenture. The New England Home for Little Wanderers strongly recommended legal adoption. Though it may be difficult in some states to access indenture and adoption records, don’t let this stop you from trying. The state of New York is particularly frustrating about opening adoption files, except under the most extreme circumstances. Indenture records were typically filed at the county courthouse, but over the years, they’ve found their way to local historical societies and college libraries, among other places.

Census records can be invaluable to the orphan train researcher. Both state and federal census records should be consulted. If you know the approximate area that your ancestor lived in, or if you happen to know the specific name of the orphanage that housed your ancestor, consulting the census records can yield results. You’ll generally find a complete listing of the children, along with month, year, county and state of birth. If foreign-born, the country of birth will be listed, as well as the state or country of birth for the parents of the children. Prior to the 1900 census, you’ll find all of the prior information, minus the month and year of birth. As with newspapers, microfilmed census records can also be ordered through interlibrary loan.

I now have a greater appreciation than ever before for my little grandmother, Emily, who was like a second mother to me while I was growing up. If she hadn’t boarded that orphan train in New York in 1906, where would she have ended up? I hope that you, too, will be able to “connect” one of your family members to the orphan trains and find your place in this chapter of America’s history.

From the June 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT