Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

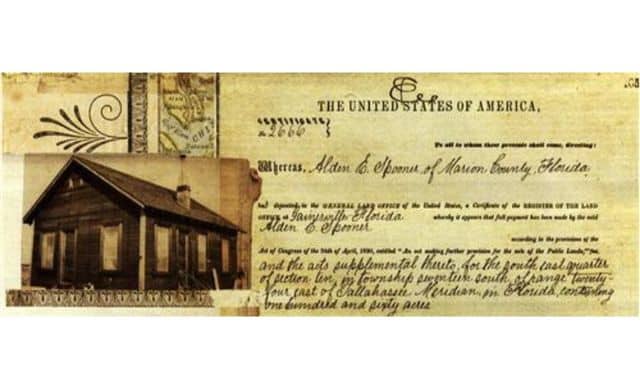

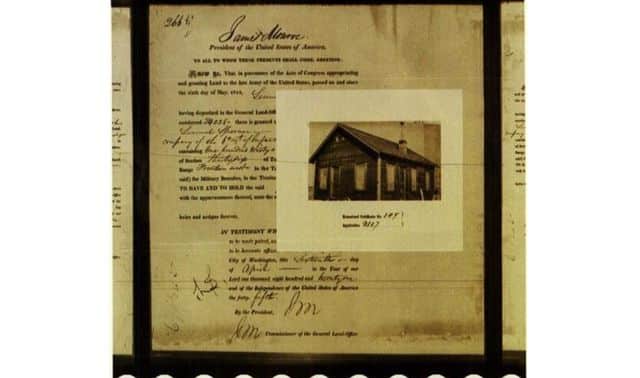

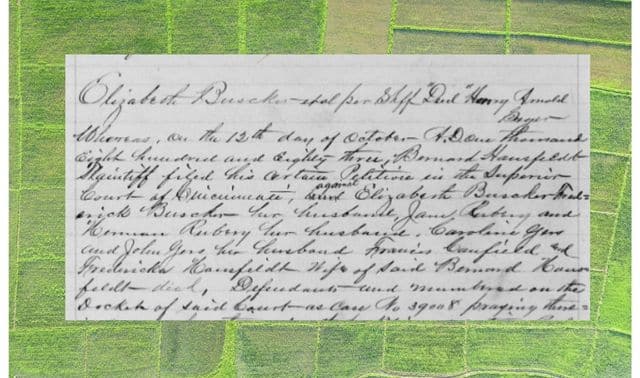

Land records often contain the solutions to our genealogical problems — identifying spouses, parents, children and earlier places of residence. But what if your ancestors bought and sold land — creating those possibly crucial family history clues — far from where you live now? How can you research deeds from a distance?

You may not have to leave your hometown to research your ancestors’ land records. Start your at-home research by clearly identifying your goal. Focus on a single problem, and identify the family, location and time period for which you want to find deeds.

Researching the Region Thoroughly

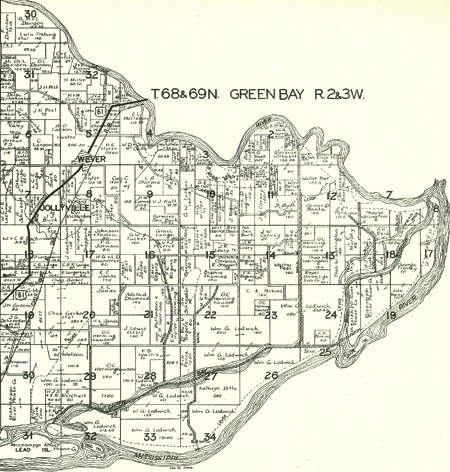

We’ll begin with something fairly basic — make sure that you’re looking in the right place. The family farm may be in Washington County, but land that is now in Washington County may have been in Jefferson County at the time your family purchased the land. It’s wise to investigate the place and time before proceeding with your research because you can save hours of misdirected effort and weeks of waiting for a reply from the wrong county courthouse.

How do you learn about county formations? (I will use county generically, but in some areas, deeds are found at the town level.) Some popular printed sources are The Handy Book for Genealogists, Ancestry’s Red Book, the Genealogist’s Handbook for New England Research and the Map Guide to the US Federal Censuses, 1790-1920.

A typical entry in the Handy Book or the Red Book would tell you (among other information) the year Washington County was formed, the county — or counties — from which it was formed, the county seat, the ZIP code of the county courthouse, and the first year for which the county has land records. They also have maps showing present-day county boundaries. For New England states, consult the Genealogist’s Handbook for New England Research to understand the peculiarities of land jurisdictions there.

The Map Guide to the US Federal Censuses, 1790-1920 shows the county-formation process visually in 10-year snapshots. Personally, I find it the most informative place to start, since I can quickly get a mental image of the process of county formations (many states had finalized their county structures by 1860, for example). Then, I check the other sources as needed. Some counties were created from two or more other counties. If you know where the family land is, you may be able to locate it on a modern map and then determine which county it came from. If you don’t know if your ancestor had land, you’ll want to check all parent counties.

If you prefer to keep your research digital, you can search the FamilySearch Online Catalog. Search for your county by place and read through the topics to find out when the county was formed and to learn the names of any parent counties. You’ll also find information on subjects such as record losses.

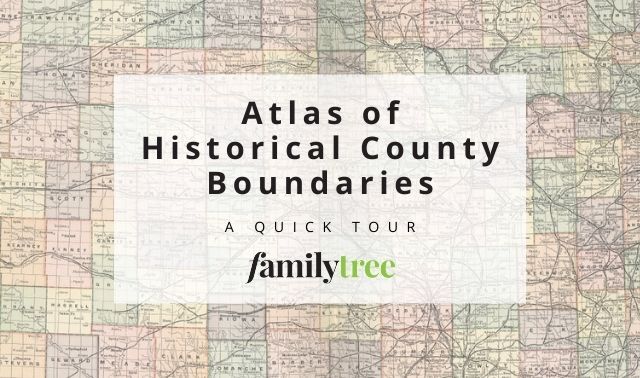

You can also search the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. This resource is helpful because it takes into account that county boundaries have been historical fluid for many centuries. Simply select the state that you would like to explore and then the interactive map. Then you can zero in on specific dates using the date selector on the left. Selecting a date will yield a map that shows the state’s county boundaries at that time. Due to even small boundary changes, you may learn that your ancestors purchased land in one county but actually lived long-term in a neighboring one despite having never left. Uncovering these subtle changes can help you determine where to turn for records.

Tracking Down Deed Books

Our instinct is to reply to the question “Where are the deed books?” by saying “At the county courthouse, of course.” That answer may be incorrect — or it may not be the only correct answer. Let’s look at the possibilities:

Original record books: Deed books originally belonged to the jurisdiction that created them, most commonly the county. But as counties became more mature and more populous, the number of record books grew. Fortunately, land records (at least, deeds) were rarely discarded. Land ownership is an important asset and one on which many facets of county business are based, from tax collection to the location of roads and easements.

To deal with the ever-growing volume of records, some counties built bigger courthouses. Some counties consigned older records to the basement or attic. Some counties began storing them off site (sometimes with ready access, sometimes not). And some counties, in effect, moved the records “up” a jurisdiction. A few states (Illinois being a prime example) established regional archives where counties could send old records for safekeeping. A number of states established programs to send older records to their state archives. This is generally an ongoing process. Not all counties have transferred records, and not all records have been transferred. Some counties are working on it; others intend to keep their records. In other words, you need to be open to a wide range of possibilities as you seek your ancestors’ land records.

This transfer process may be influenced by whether or not the originals have been recorded on microfilm, microfiche or other storage media. If a county knows it can still refer to its records quickly and easily, it may be more likely to transfer the originals to another location, either off-site storage or a regional or state archive. Some counties that still possess their original record books won’t let you look at them — you’ll have to look at the microform version.

Microform: Commercial vendors of microform systems have long seen the problem of record storage and retention for county offices as a business opportunity. Many counties purchased some kind of microform system in which the vendor made copies and provided equipment to access the copies. To say that there is a wide variety of systems would be an understatement. Many of them are heavily proprietary — meaning the vendor’s equipment is required to read the records. A number of state archives also undertook microfilming programs for the records in their possession.

Microfilm: For the United States, land records are an important — and voluminous — portion of the collection. In general, the original 13 colonies and the first tier of trans-Appalachian states have been microfilmed, but much smaller portions of the counties in the Midwest and West are covered. While FamilySearch discontinued its microfilm circulation service in 2017, you can still search for and access over 2.4 million rolls of microfilm using the FamilySearch Catalog online. The best part is that you don’t even have to travel to Utah!

Published abstracts: You may be lucky. A dedicated genealogist or society volunteer may have abstracted the indexes or the deed books you need and published them in books or in a genealogical society’s periodical. Published abstracts are valuable for several reasons. It’s easier and faster to check the index of a book than to crank microfilm or drag heavy volumes from courthouse shelves. Plus, information about your ancestor may be buried in a deed in which neither the seller nor the purchaser is a familiar name to you. The every-name index in a book of abstracts may lead you to a deed you would have otherwise overlooked. Southerners often must rely on land records to learn anything about their ancestors, and so they have been especially proactive in publishing abstracts.

Online land records: It can be difficult to find county-level land records online, mainly because of the sheer volume of records. In a few cases, volunteers may have abstracted deed indexes to be placed on websites or county offices or state archives may have placed their indexes online.

Finding and Studying Published Records

So how do you start accessing your ancestors’ land records? Begin by determining if there are published abstracts for your area of interest. Second, look for microfilm. Third, see what’s online. Fourth, do it the old-fashioned way — write a letter.

I like to start my searches with the FamilySearch Catalog because it lists more books of deed abstracts than does any other single source. It can be used to track down deed books and indexes of over 1,500 counties and towns. For your county of interest, look at the topics for Land and Property and for Land and Property — Indexes. If the categories aren’t there, the library has no land-record holdings for that county.

Published books will have entries such as “Washington County Deed Books A and B, 1788-1797. Abstractor Abbie.” Once you find an item in the online catalog that seems a likely fit, click on the title. The screen that appears contains a detailed catalog entry. Write down the title, author and all publication information (it’s at the bottom of the screen, so you may need to scroll down to get it all).

Of course, your options aren’t limited to the FamilySearch Catalog. Check the online catalogs of the nearest library with a genealogical collection, libraries with good genealogical collections around the country, the state library for your area of interest, and smaller libraries in your area of interest (remember to search for historical and genealogical society libraries). And don’t forget the Library of Congress online catalog.

Abstracts also may appear in periodicals. And with the electronic version of the Periodical Source Index (PERSI), finding them is easy. PERSI was developed by the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, Ind., and originally published in book form with annual updates. In 1999, the library worked with Ancestry.com to produce an electronic version of the constantly growing database. Many libraries have a subscription to Ancestry.com that you can use to search periodicals.

PERSI has three major sections: surname, locality and general subjects. Finding land records is easy. Search the US Locality Section for the record type land, and enter the name of the state and county. There are about 20,000 such entries in PERSI. When you find an article that looks interesting, you can click on the periodical name to display a list of major libraries that hold the periodical.

Once you’ve found a printed book or periodical that has land-record abstracts of interest, you’ll need to access the actual publication. Here are some steps to take to get it:

- Begin by checking to see if the genealogical collection nearest you has a copy.

- Consult with your local librarian about interlibrary loan. Although most genealogical collections do not circulate their books, a few do. Supply accurate information about the author, title and publisher.

- If you found the item in the FHL catalog, look to see if it is on microfilm. If so, you can borrow the microfilm at your local Family History Center.

- If the book is still in print, consider purchasing a copy. After you have completed your research for that locality, you can donate it to the genealogy collection nearest you.

- Consider hiring a researcher to check the book for you (see next page).

- Contact the library and genealogical society in your area of interest to ask if they will check the index for you. Inquire about fees and copies. You may want to join the society, especially if you will have much research to do there — sometimes research services are available to members, but not nonmembers. If the library and genealogical society are helpful, consider making donations.

Reading Microfilm

While FamilySearch no longer maintains a microfilm loan program, you can access millions of digitized microfilms using the online catalog. The FamilySearch Catalog can be used to track down deed books and indexes microfilm numbers of over 1,500 counties and towns. To search, select Place, type in your county and state (formatted County, State) and then look for records labeled “Land and Property.”

The Film Notes page lists the roll numbers of corresponding microfilmed grantor and grantee indexes to deeds. These often cover more than a century. Read the index rolls to identify all the deeds of your ancestral family. Write down every entry — in full — for every family member.

Here are some tips for success with microfilm:

- Search both grantor and grantee indexes.

- Do not focus on only your ancestor.

- Remember that your ancestor’s siblings had the same parents as your ancestor. Consult your family group sheets for the names of extended family.

- Make a list of the names of brothers-in-law and sons-in-law. It’s easy to forget them in a surname-focused search.

- Copy all index entries for a surname. This will save you a step if you later discover the names in the index are relatives.

Searching for Land Records Online

As mentioned earlier, there aren’t many online indexes to land records. But you should always check. Look for indexes done by volunteers — and for indexes done by the county. The three major sites to check:

If none of these provides a link to the government website for the county you’re researching, you should also do a general Web search for it.

Obtaining Land Records Through County Court Houses

We used to find deeds for our ancestors by writing the courthouse. Of course, that option is still available to you

When you write a courthouse, remember that answering mail from out-of-state family researchers is not the staff’s primary job. Its primary job is to serve the citizens and taxpayers of the county and to perform needed county tasks. Keep this in mind and be patient and polite when contacting a courthouse. Be both concise and complete in your request. Don’t impart extraneous information — and make sure you’ve provided all the needed information.

There are a number of ways to find contact information for local courthouses, as well as for libraries and genealogical societies you may also want to write. Several printed sources, such as County Courthouse Book and The Ancestry Family Historian’s Address Book (see opposite page), are often used to obtain phone numbers and mailing, e-mail and Web addresses. Many genealogical collections have these books.

Many researchers rely on Cyndi’s List to get current information. Look under Libraries, Archives & Museums; Societies & Groups; or the United States Index for the locality you’re researching.

Hiring a Professional Researcher

You may find that the best (or only) option available to you is to hire someone to examine books and records or to obtain copies. If the records or books are available with FamilySearch, you could choose to hire a researcher either in Salt Lake City or in the county or state where the land records are archived.

There are three organizations of professional researchers that you should check. The members of all three organizations have signed codes of ethics. Two of the three have testing procedures. Each has a Web site that explains the organization and lists its researchers:

- Board for Certification of Genealogists

- International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists

- Association of Professional Genealogists

When you forward information to a professional researcher, follow these guidelines:

- Provide concise, accurate and complete information about your ancestors. This means no rambling letters, phone calls or e-mails about your family history and its interesting legends.

- List exactly what you’ve already found.

- Specify what you want done.

However you remotely research land records, you’ll find these documents filled with clues that your ancestors had no idea they were leaving behind. Your ancestors thought they were merely buying home sites, acquiring farmland or selling plots of land; little did they suspect that they were also leaving a genealogical legacy for you to find.

Summarizing My Genealogy jaunts

Some of us like to spend our vacation time looking for deeds, but we’re not fond of driving from courthouse to courthouse. We take our vacations in Utah instead!

Early in my genealogical research, I began adding several days onto ski trips in order to remain in Salt Lake City and peer into a microfilm reader at the Family History Library. During the summer, families can visit national parks and hike in the mountains. The researcher in the family can stay on for a few extra days to search for ancestors. Your Guide to the Family History Library (see page 52) offers extensive, helpful advice on planning a trip, including information on hotels, restaurants and activities for the non-genealogist.

Land records have always been a focus of my research at the Family History Library because of the large number of rolls of microfilm I need to check. It’s not exactly instant gratification, but it’s much more efficient to read an index and walk 40 steps to retrieve the film for the deed book than it is to wait several weeks for each roll of microfilm. I justify it to myself financially by thinking of how many film-rental fees I’m saving!

Toolkit

Books*

The Ancestry Family Historian’s Address Book by Juliana Szucs Smith (Ancestry)

Ancestry’s Red Book: American State, County and Town Sources, revised edition, edited by Alice Eichholz (Ancestry)

County Courthouse Book, 2nd edition, by Elizabeth Petty Bentley (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

Genealogist’s Handbook for New England Research, 4th edition, by Marcia D. Melnyk (New England Historic Genealogical Society)

The Handy Book for Genealogists, 10th edition (Everton Publishers)

Map Guide to the US Federal Censuses, 1790-1920 by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

“Printed Land Records” by Wendy B. Elliott and Karen Clifford, in Printed Sources: A Guide to Published Genealogical Records edited by Kory L. Meyerink (Ancestry)

Your Guide to the Family History Library by Paula Stuart Warren and James W. Warren (Betterway Books)

Web sites

Cyndi’s List: This directory of genealogy Web sites contains more than 175,000 links.

FamilySearch Catalog: A fast and easy-to-use CD-ROM version also is available for purchase on the site for $5.

Periodical Source Index (PERSI): An invaluable resource, PERSI is housed at the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center and can give you access to countless periodicals, newsletters, journals and more to guide your genealogical research.

RootsWeb: This organized, linked system of volunteer-created Web sites includes information on land-related topics and research in specific locations.

USGenWeb: Organized by volunteers, the USGenWeb Project aims to provide genealogy researchers with resource-packed Web sites for every US state and county.

From the April 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Updated in August 2022.

*FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.

Related Read

ADVERTISEMENT