Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Just about everyone has a relative who answered Uncle Sam’s call to arms, and the resulting records rank right up there as one of the best genealogical sources you can get: Military service papers and pension applications tell you details about a soldier’s life, his family members, and the time and places he served. Those who didn’t join up still might appear in draft registration records or a relative’s pension application.

But some of these records haven’t been easy to get — requiring renting (and then waiting for) microfilm from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) or the Family History Library. Entire collections, such as Civil War pensions, aren’t yet microfilmed, and you have to visit NARA in Washington, DC, or pay (through the nose, some might say) to order paper copies by mail. To rectify the situation on a tight budget, NARA has turned to partnerships with other organizations — notably Ancestry.com, Footnote and FamilySearch — which have digitized, indexed and posted thousand of records. And these and other sites, such as HeritageQuest Online, already had images of military records from NARA microfilm and books of muster rolls.

With this confusing array of online options, how do you know whether you still have to order records by mail or if they’re on the Web? And what site should you start with? Our maneuvers will help you navigate to genealogical records from the Revolutionary War through the Vietnam War.

Revolutionary War

There’s a good chance your Colonial-era male ancestor of age fought in the Revolutionary War — and not necessarily for those seeking independence. Follow our formula to find his records online.

Muster rolls in family and local histories can help you determine if your ancestor fought in the Revolutionary War. For instance, a history of Haverhill, Mass., says my ancestor James Snow, a member of Capt. James Sawyer’s company, trained as a minuteman in spring 1775. This and other histories are part of HeritageQuest Online, searchable free through subscribing libraries (contact your library to ask about the service and whether you can log on from home via the library’s Web site). Footnote ($79.95 a year) also has digitized muster rolls.

Records of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) may reveal a Patriot in your tree. Start searching with Ancestry.com’s ($155.40 per year) DAR Lineage Books database of 2.4million names from DAR membership applications. (If you’re not an Ancestry.com subscriber, see if your library offers Ancestry Library Edition.) Search by the applicant (in the given name and surname boxes) or the patriot ancestor (using the keyword box). You can order a copy of the membership application for $10 following the online instructions. The lineage books may contain errors — documentation requirements weren’t always as stringent as they are now. Fortunately, more-recent members have updated much data. You also might find your ancestor in the DAR Patriot Index, a three-volume set with facts on 100,000-plus people. Request a free lookup online.

Revolutionary War pension files may reveal a birthplace, description of service, postwar residence and pension amount. They’re digitized on HeritageQuest: Click Search Revolutionary War, then enter some combination of given name, surname, state and unit of service. Select a last name in the matches to see the pension application; use the right arrow on the Image button to view other pages in the file. Click Download to save the file to your computer. These records are from NARA microfilm M805, which includes up to 10 pages from each soldier’s file, but has only significant genealogical documents from larger files.

Footnote, though, offers NARA microfilm M804, which includes the entire pension files. Click Browse and select Revolution: 1775-1815 as the category, and Revolutionary War Pensions as the title. Optionally, select a state and scroll down to enter a name in the search box.

If your Revolutionary-era relative sided with the British Crown, try the free Loyalist records in the On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies. In addition to a muster roll index, you’ll find regimental documents, land petitions and postwar settlement papers. Be sure to look for variant spellings: I couldn’t find my ancestor James Pennington, a soldier in the Queen’s American Rangers, until I tried entering Penington — a muster roll showed he was taken prisoner July 20, 1779.

Land-rich and cash-poor, Uncle Sam issued bounty-land grants to eligible veterans of the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, part of Ancestry.com’s US War Bounty Land Warrants, 1789-1858. Typical information includes the veteran’s rank and regiment, and the date the warrant was issued. HeritageQuest’s Revolutionary War database includes bounty-land warrant application files.

War of 1812

Despite its name, the War of 1812 with Great Britain lasted until 1815. The conflict involved about 60,000 US Army forces and 470,000 militia and volunteer troops, but only about 2,000 of them were killed. War Hawks came mostly from the Western and Southern states, while New Englanders generally opposed going to war.

Start your search with the War of 1812 Service Records Index on Ancestry.com , which lists almost 580,000 soldiers mustered into the armed forces between 1812 and 1815 (some soldiers are listed more than once). If you’re dealing with a common name, enter the soldier’s state in the Keywords box. Each record includes the name, company, and rank at induction and discharge. Use the microfilm roll information to order records from NARA.

The government originally awarded pensions only for service-related deaths and disabilities, but 1870s laws granted pensions based on service alone. Most War of 1812 veterans had died by then, but their survivors might have filed for pensions. Browse for your ancestors in Ancestry.com’s War of 1812 pension application index, by choosing from a list of alphabetical ranges, then guessing at image numbers — the going is slow unless you have a fast Internet connection. Looking for James Hall, I finally found several in the H-Hame range on images 463 to 479; for most, the index card gives a state of residence, service information and widow’s name. Use the information on the card to request a copy of the pension application from NARA.

• Bounty-land warrants for these veterans are with Revolutionary War soldiers’ on Ancestry.com.

Civil War

The military service of the 3.5 million Civil War soldiers generated mountains of records, and their popularity has made them a digitization priority. Only a fraction of records are online as yet, but indexes are plentiful. Knowing your ancestor’s state and unit number will help ensure you get the right files from NARA, especially if your soldier had a common name.

The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS) has service information on 6.3 million names of Civil War soldiers (those who served in different units are listed more than once) taken from NARA’s General Index Cards to Union and Confederate soldiers. You’ll also find regimental histories, battle descriptions and prisoner records. Ancestry.com has a similar soldier index.

Service records may give the soldier’s place of birth and dates of enlistment and discharge, and describe battle wounds, illnesses and medical treatment. Footnote is digitizing and posting Confederate service records for subscriber access. Click the down arrow by Browse and select Civil War, then Confederate Soldier Service Records. Optionally, choose a state and unit. Scroll down, enter a name in the search box and hit Go. (NARA has microfilmed Confederate service records; rent the film from the Family History Library by visiting a Family History Center near you.)

Part of the special 1890 census of Union veterans and widows survived the fire that ruined the rest of that year’s enumeration. If your veteran ancestor lived in Washington, DC, or one of the states alphabetically from Kentucky to Wyoming, you’re in luck. Look for his name in Ancestry.com’s 1890 Veterans Schedules database. Just remember that the information, recorded 25 years after the fact, might have errors caused by foggy memories — two of my 1890 relatives named the wrong unit.

The American Civil War Research Database ($25 per year, or $10 a week for just service information) summarizes a variety of resources, including state rosters, pension indexes, regimental histories and Rolls of Honor. Use it to identify a soldier’s service dates and unit, as well as the unit’s casualty statistics. Ancestry.com has a version of this database, but it’s not updated often.

A Civil War veteran, his spouse or other family members could file for a pension. Eventually, due to a partnership, you’ll be able to view images of Union pension records at Footnote with a subscription, or at Family History Centers for free. For now, look for an online pension application index. The free FamilySearch Record Search pilot site has added a database of Union pension index cards (it also includes some veterans of the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection and World War I). Click Record Search and select the database in the Military section. Enter the soldier’s name and, optionally, narrow your search by typing his state of enlistment in the Place field.

You can search transcriptions of the same Civil War Union pension index cards for free on Footnote. Click on the arrow beside Browse by Historical Era and select Civil War. Under Title, click Civil War Pensions Index and then, optionally, choose a state and branch of service. Scroll down, enter a name in the Search box and hit Go. Ancestry. com also has a pension index, searchable by the state where the application was filed (not necessarily the state from which the soldier served).

The former Confederate states granted pensions for their veterans, so application records aren’t centralized. Look for online indexes at state archive Web sites; Florida and Georgia even have the actual records online. For more help, see NARA’s links.

Spanish-American War

Just 280,564 American sailors, marines and soldiers served in the Spanish-American War — far fewer than in the Civil War and the two World Wars. Engagements took place mostly in Cuba and the Philippines. Of those soldiers, 2,061 died from various causes. The Spanish-American War Centennial site has rosters and historical information. You’ll find a surname index to Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders on the free Access Genealogy site; that unit’s service records are online in NARA’s Archival Research Catalog. Order copies of other soldiers’ service records and pension files from NARA.

Philippine Insurrection

More than 125,000 American soldiers served in the Philippines; 4,000 of them died during the conflict. The 1900 US census covered military personnel stationed in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

In Ancestry.com’s 1900 census database, select Military and Naval Forces as the state of residence. In HeritageQuest Online, select Military and Naval as the state. My relative Charles A. Adsit of Cuba, NY, is listed as a 30-year-old musician stationed in the Philippines in the 13th infantry’s Company E. Ancestry. com’s military collection also has books with rosters from a handful of states. You can order service and pension records from NARA.

World War I

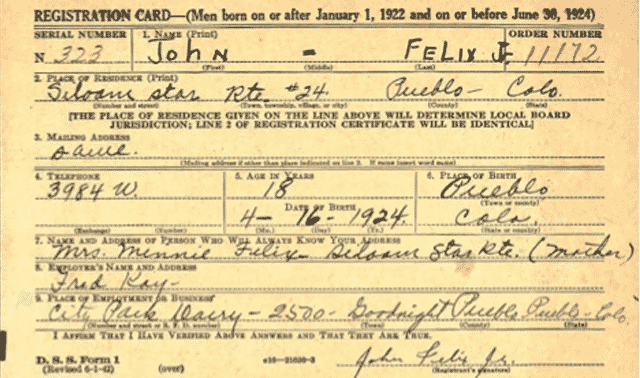

In 1917 and 1918, about 24 million male residents of the United States completed WWI draft registration cards. All men born between Sept. 11, 1872, and Sept. 12, 1900 — about a quarter of the US population — had to register. Those records are part of Ancestry.com’s military collection, with images showing full name, residence, date of birth, occupation, physical description and name of the nearest relative.

World War II

Most 20th-century military personnel records, including many files for the 16.5 million men and women in World War II, were lost in a 1973 fire — but you still can find WWII veterans in online records.

Seven WWII draft registrations occurred between 1940 and 1943, but due to privacy restrictions, only the fourth — the “old man’s registration” of those born between April 28, 1877, and Feb. 16, 1897 — is open to the public. (Those men weren’t liable for military service, so you’re unlikely to find service records for them.) Information on the registration cards includes place of residence, date and place of birth, employer and the nearest relative.

Ancestry.com’s WWII Draft Registration Cards, 1942, has draft cards from 17 states; more will be added as NARA microfilms them. The free FamilySearch Labs also is adding the card images to its Record Search. Fourth-registration draft cards for most Southern states were mistakenly destroyed without being microfilmed, so they’re lost for good.

Look for those who joined up in WWIIArmy Enlistment Records, 1938-1946, on NARA’s free Access to Archival Databases (AAD) site. The 8.3 million records cover most men and women who served in the Army during the war, and include residence, place of birth, and height and weight.

Korean War

Privacy concerns have kept most post WWII records offline. But AAD has four files of casualty lists — military personnel who were injured, died or taken prisoner.

Vietnam War

AAD has three Vietnam War casualty list files. You also can browse states’ lists. Footnote’s free Interactive Vietnam Veterans Memorial lets you search or browse for names of those killed in the war. Each records links to an image of the name on the Vietnam memorial wall in Washington, DC, and details about the soldier.

For additional help finding your family tree online, try Family Tree Magazine‘s Trace Your Roots Online CD, which offers sites, tips and tools for genealogy on the web. Available from Family Tree Shop.

ADVERTISEMENT