Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Whether you’re upgrading an old computer or buying a new one, you need to make a few decisions — and your needs as a family history researcher may be different from those of the ordinary customer at your computer superstore. Here are a few key questions and some advice to help you answer them from the genealogist’s perspective:

Windows or Macintosh?

A computer’s operating system (OS) is the software that controls all the other programs on your computer and how they interact with your printer, scanner, CD-ROM drive and other devices. Virtually all personal computers use one of two operating systems, either Macintosh OS or some version of Windows. Some software companies create both Windows and Mac versions of their programs, but most programs run under only one operating system or the other.

In almost every area, you’ll find far more software available for Windows computers than Macs — and genealogy software is no exception. You can choose between at least nine full-featured genealogy programs for Windows, but only a couple for the Mac. (See the Family Tree Yearbook 2002 for a quick guide to these choices.) Also, you’ll find a lot of Windows CD-ROMs with census records, pedigrees and other databases, but only a few genealogy CDs that will run on a Mac.

Expect to pay more for a Mac than for a Windows computer with comparable hardware. Macs are more stylish and generally easier to set up and run, but usually less customizable and expandable than Windows computers. Both can connect you to the Net.

If genealogy is your primary reason for getting a computer, you’re probably better off buying a Windows machine. But if you already have a Mac or will use the computer for professional graphics work or other functions where the Mac excels, rest assured that you can make good use of the Mac for genealogy, too.

Buying new: Most Windows computers for personal use come with the new Windows XP.

Upgrading: Almost all Windows programs require Windows 95 or higher, so you should upgrade (or get a whole new computer) if you have an older version. If you have Windows 95, 98 or ME, consider upgrading to Windows XP, which features better backup, lets users talk directly to each other via their PCs and crashes less often than older versions. Windows XP requires at least a 300MHz processor, 128MB or more RAM, 1.5GB of free hard disk space and a CD-ROM or DVD-ROM drive.

Desktop or laptop?

If you do most of your genealogy work from home, a desktop computer may suit your needs just fine. But if you spend much time researching in libraries and archives, a notebook computer (or “laptop”) makes a nice replacement for a bulky three-ring binder filled with charts and blank paper. You’ll be able to quickly access information on any individual in your genealogy files and type notes much faster than you could write them down with a pen and paper. And you can easily share the notes you’ve written on your computer with your e-mail correspondents.

Many laptop computers will run off a battery for two hours or more, although most libraries provide electrical outlets to plug in your notebook. Call ahead to check on the library’s policies and take along a lock so you can secure the laptop to a desk or table while you retrieve books. A laptop also makes it easy to access the Internet and send and receive e-mail while you travel — provided you have access to a phone jack and your Internet access provider has a local phone number for your location or a toll-free access number.

While laptop computers are convenient for the researcher on the road, they do have a few tradeoffs. First, a laptop will cost about twice as much as a desktop computer with the same features. Second, a laptop’s keyboard is smaller and harder to type on. Finally, while desktop computers usually have lots of room inside the case for adding new components, laptops can’t readily be opened up and have limited upgrade potential. So you’ll probably get fewer years of productive use out of a laptop before you’ll want to buy a new computer.

Laptop computers range from ultra-lightweight models weighing only 2 pounds to desktop replacements tipping the scales at 7 pounds or more. The smallest models will easily fit in your briefcase and have a longer battery life, but they have smaller screens and may lack an internal CD-ROM drive. Larger notebooks are less convenient if you travel a lot, but bigger screens, keyboards and hard drives make them more suitable substitutes for your desktop.

A handheld computer (also called a personal digital assistant or PDA) is another option for the traveler, but you’ll still want either a desktop or notebook computer. Then you can use genealogy software on your main computer to enter your data and copy it to the handheld computer for reference on the road. buying new: Get a desktop computer if you won’t be doing much research away from home. Go for a larger laptop with a big screen if you want one computer that will work well both at home and on the road.

Upgrading: If you already have a desktop computer, you might consider getting an inexpensive, lightweight laptop for research trips and family reunions.

A 15-, 17- or 19-inch monitor?

Desktop computers typically come with a 17-inch monitor; laptop displays range from 12 to 15.7 inches. Laptop displays fill the full screen, so a 15-inch laptop screen shows roughly as much as a 17-inch desktop monitor.

Buying new: A new computer system with a 17-inch monitor costs only a little more than one with a 15-inch monitor, and the larger monitor will be a lot easier on your eyes. Keep in mind, though, that a high-quality 17-inch monitor may be better than a lower-quality 19-inch one. For a sharp display, select a monitor with a dot pitch of .28mm or less. Flat-panel monitors reflect less glare than curved tube monitors and, like laptops, use more of the available screen space. If you get a chance, compare monitors side by side in a store.

Most laptops have either an SVGA display (800×600 pixels) or a sharper XGA display (1024×768 pixels). If you buy a laptop, spring for an active-matrix or TFT screen, since it provides a bright display readable under a variety of lighting conditions.

Upgrading: If you have a 15-inch monitor or your old monitor has grown dim, consider a 17-inch replacement for $200 or less or a 19-inch one for $300 or less. Flat LCD(liquid crystal display) monitors are just a few inches thick, take up a lot less desk space than tube monitors and deliver crisper images. Prices on LCD monitors are plummeting — you can get a 15-inch model (equivalent in viewing area to a 17-inch tube) for less than $300.

800MHz or 2GHz?

The CPU or microprocessor is your computer’s brain and generally determines how fast your programs will run. A Pentium processor running at 100MHz (megahertz) is the minimum you need to run most genealogy software, but at least 166MHz is recommended.

Buying new: New computers now have CPUs with various flavors of Celeron, Pentium and Athlon processors ranging from 800MHz to 2GHz (2 gigahertz equals 2,000MHz). An 800MHz CPU is more than sufficient for most programs such as genealogy software, e-mail and word processing. Consider a faster machine if you will be editing home videos or playing 3-D games.

Upgrading: It’s possible to replace your computer’s CPU with a faster one, but not really economical now that whole computer systems are so inexpensive. If your computer has a 100MHz or slower processor, seriously consider getting a new computer.

128MB or 256MB of memory?

While running, computer programs need space in memory (RAM, short for Random Access Memory). If your computer has sufficient memory, you can easily run several programs — genealogy software, a word processor, an e-mail program — all at the same time. Most genealogy software for Windows requires at least 16MB (megabytes) of memory, but 32MB or more is recommended.

Buying new: New computers generally have 128MB or 256MB of memory. Memory is cheap; don’t settle for less than 128MB. Go for 256MB if you’ll be doing much work with digital photographs or video editing.

Upgrading: If your computer has less than 32MB of memory, consider adding more to improve performance. Make sure the speed and type of memory you add is compatible with what’s already installed.

10CB or 80GB of hard disk space?

Every program you install on your computer takes up space on your hard disk drive. Data files, such as word processing documents, e-mail messages, scanned photographs and data you’ve entered in your genealogy software, also take up space. Most genealogy programs need between 20 and 50MB of hard disk space and you’ll probably want at least another 50MB free to hold your family information, not to mention more space for other program and data files. These days, hard drives are measured by the gigabyte (GB, or “gig” for short), which equals 1,000MB.

Buying new: Hard drives in new desktop computers usually range in size from 20GB to 80GB and those in laptops from 10GB to 32GB. It will take most users a very long time to fill up even 10GB of space, but get at least a 30GB hard drive if you plan to store a lot of photographs and videos.

Upgrading: If your hard disk is almost full, you might copy some scanned pictures and old word processing documents to a CD-R disk (see page 26) to free up space. Otherwise, consider replacing your hard drive with a larger one or, if your computer has room, adding a second hard drive.

Sample systems

Here’s a sample of complete computer systems, each including a printer and scanner. Particular brands and retailers are mentioned only as examples. Use these three sample systems as starting points to help you choose options that fit your needs and budget:

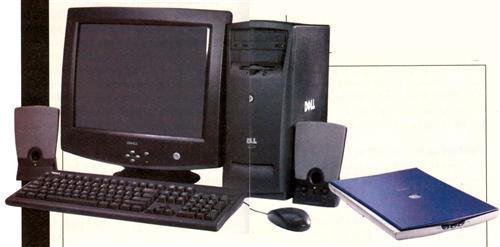

The budget family historian

Dell Dimension 2100, 900MHz Celeron, 128MB RAM, 20GB hard drive, CD-ROM, 56Kbps modem, 15-inch monitor, six months of AOL dial-up Internet access; priced starting at $649.

Add an Epson Stylus C60 InkJet printer for $99, a 10-foot parallel cable for $16, a Canon N670U flatbed scanner for $99 and an Ethernet network card for $20. Total system: $883.

An excellent value, this setup will fill the needs of most genealogists. Consider upgrading to a 1GHz Pentium III for $50 more and a 40CB hard drive for $50 more. Dell, <www.dell.com>, (800) 388-8542

The multimedia genealogist

Hewlett-Packard Pavilion 7950, 1.2GHz, 128MB RAM, 60CB hard drive, DVD, CD-RW, 56Kbps modem with integrated Ethernet network support, an HP MX90 19-inch monitor and premium Polk Audio speakers. Bundled software includes Microsoft Works, Encarta and Money, ArcSoft My Photo Center and Pinnacle Systems Studio for digital video editing; $1,548.

Add 128MB more RAM for about $50, a Pinnacle Systems Studio DC10Plus PCI video-capture board for $no, an HP Deskjet 940c printer for $150 and an HP Scanjet 5470c for $300. Total system: $2,158.

While it’s overkill for most users, a fast processor, lots of memory and hard drive space and a video-capture card make this system ideal for work with video. You’ll be able to transfer video from a camcorder or VCR to your hard drive, edit the video and create a multimedia family history. And this system features a 2,400 dpi scanner and near-photo-quality printer so you can scan slides and negatives and make good prints as large as 8×10 inches. PC Connection, <www.pcconnection.com>, (888) 213-0260.

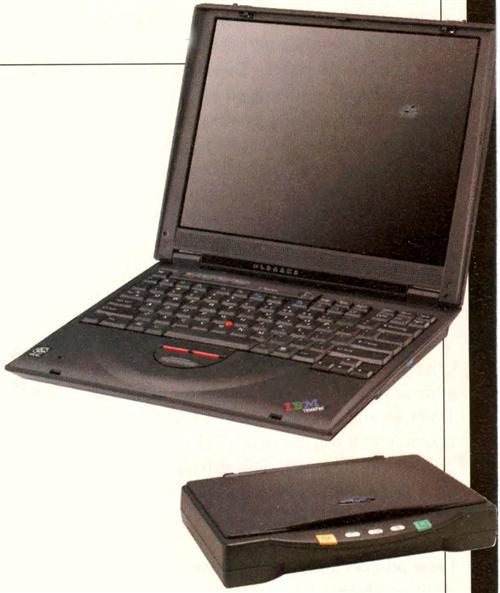

The mobile researcher

IBM ThinkPad i Series 1200, 700MHz Celeron, 64MB RAM, 10CB hard drive, CD-ROM, 56Kbps modem, 13.3-inch XGA TFT display, carrying case, Lotus SmartSuite and Quicken Basic software;$999.

Add an external CD-RW drive for $250, an Ethernet network card for $109, a mouse for $49, a Canon BJC-85 BubbleJet portable USB printer for $299, a printer cable for $6 and a Visioneer 8100 OneTouch Scanner for $100. For a scanner you can tote anywhere, add the Siemens Pocket Reader <www.pocketreader.com>, a $100 handheld model that scans one line of printed text at a time. (Or to scan handwriting and hard-to-read fonts, try the more powerful Wizcom QuickLink Pen <www.wizcomtech.com> for $179.) Total system: $1,912.

This 7-pound system packs a lot of power in a small package and should serve you well whether you’re researching from home or traveling to courthouses and libraries. IBM, <www.pc.ibm.com>, (888) 746-7426

CD-ROM, CD-RW or DVD-ROM?

In addition to a 3 ½-inch (1.44MB) floppy disk drive, almost all computers have at least one of these high-capacity removable-disk drives:

•CD-ROM — A CD-ROM (compact disc — read-only memory) holds up to 650MB of data. Before you can run a new program, you usually need to install it on your computer by copying files from a CD-ROM to your computer’s hard drive. A CD-ROM drive can also play music CDs.

•CD-RW — A CD-RW (compact disc — rewritable) drive lets you create your own CD by writing data to either a CD-RW disc or CD-R (compact disc — recordable) disc. You can copy files to a CD-RW, then erase them and record new data, so a CD-RW disc works like a large-capacity diskette. CD-RW discs can’t be read by most older CD-ROM drives, so they’re not good for sharing files with friends.

You can use CD-R discs only once. Since they can be read by most regular CD-ROM drives, however, they’re ideal for sharing files, like scanned pictures or a large genealogy database, with your correspondents. And they’re throwaway cheap.

Just in case disaster strikes, it’s a good idea to back up (create a copy of) the data files on your computer regularly. Diskettes work fine for backing up a few small files, but CD-R discs are perfect for larger-volume backups.

•DVD-ROM — A DVD (digital video disc or digital versatile disc) looks like a CD-ROM, but can store 4.7GB — more than seven times as much as a CD. Improved DVD-ROMs will soon have a capacity of 17GB.

Buying new: Since it can read regular CD-ROMs and create CDs, a CD-RW drive is a better choice than a CD-ROM drive for most users. With a 4X-speed CD-RW drive, you can record a CD in less than a half-hour. Few genealogy or other software titles come on DVD, so you can do without a DVD drive.

Upgrading: If you have just a CD-ROM drive, consider adding a CD-RW drive so you can back up large files and create your own CDs.

Laser or ink-jet printer?

Laser printers and ink-jet printers both offer distinct advantages. Consider these factors when choosing between them:

•Cost: Ink-jet printers are cheaper than laser printers, but ink-jet supplies are more expensive. Expect to pay between $50 and $200 for a personal ink-jet printer and between $150 and $300 for a personal laser printer. Personal laser printers don’t print in color, though. While some color laser printers have dropped below $1,000, they’re still too expensive for most home users.

A page printed in monochrome text costs between 2 and 3 cents per page with a laser printer and between 2 and 4 cents per page with an ink-jet printer. You can use plain printer paper that costs about a penny a page with either one. Or, for higher-quality color printing with an ink-jet, you might spend about 10 cents a page for coated paper or between 50 cents and $1 per page for glossy paper (see page 21).

•Output quality: If possible, compare printouts from different printers before you buy. A laser printer does a good job printing black-and-white photographs and prints sharper text than an ink-jet. Almost any ink-jet printer today produces near-photo-quality output, in black and white or color. A page printed with an ink-jet printer will smear if it becomes wet, but you can use a highlighter marker on a laser-printed page without any smearing.

•Speed: A laser printer is considerably faster than an ink-jet printer; print speed is especially important if you print a lot of pages. When selecting either an ink-jet or laser printer, get at least 600 dpi (dots per inch) to print good pictures. If you opt for an ink-jet printer, get one with black and three colors. Ink-jet printers are available in portable models that make an ideal companion for a laptop computer when you’re on the road.

Your choice of a laser or ink-jet printer will depend on how you expect to use it. If you’ll be printing mostly text and old black-and-white photos, you’ll appreciate the laser printer’s speed and lower cost per page. But if you want to print color pictures, too, an ink-jet printer is a better choice. To take advantage of the benefits of both you might consider hooking up both a laser printer and an ink-jet printer to your computer.

Upgrading: If you have a dot-matrix printer, a 300-dpi laser printer or an old ink-jet printer, consider getting a new printer.

Flatbed or film scanner?

You’ll need a scanner to get your photographs into your computer so you can e-mail them to friends, put them on a Web site or insert them in a wall chart or book.

A flatbed scanner looks much like a photocopier. Just insert a photo face-down under the cover and the scanner takes a picture of the image and saves it as a file on your computer. You can also scan typed or printed pages and use OCR (optical character recognition) software to convert the scanned material into text and avoid typing it in by hand.

Expect to pay between $60 and $200 for a flatbed scanner. Scanners usually come bundled with not only scanning software, but also basic photo-editing and OCR software. In addition to price and the software bundle, also consider the scanner’s resolution, speed and color accuracy. A scanner with a higher optical resolution — measured in dpi — will make a more detailed scan. A 600×1200 scanner resolves 600 dpi horizontally and 1,200 dpi vertically. The horizontal component is the important one, so this scanner would be called a 600-dpi model.

All good flatbed scanners have an optical resolution of at least 600 dpi. You need only 72 dpi for images that you’ll put on a Web site, but 300 dpi for graphic images you’ll print and at least 600 dpi to print high-quality photos. Some flatbed scanners come equipped with an adapter for slides and negatives. For the best high-resolution scans from slides and negatives, however, you really need a film scanner with at least 2,400 dpi.

Buying new: Get a flatbed scanner with a resolution of 600 dpi for general use. You’ll need 1,200 dpi and a transparency adapter if you’ll be scanning slides and negatives. A USB port transfers data much faster than a parallel port, so get a scanner with a USB connection if your computer supports it. Get a separate film scanner with at least 2,400 dpi if you’ll be scanning many slides or negatives. If your scanner doesn’t capture colors accurately or operates too slowly, consider getting a new one. Get a film scanner for the best scans from slides and negatives.

A sound card and video-capture card?

Most genealogy software now lets you edit photos, create a slide show or put together an interactive scrapbook with photos, sound and video. To take advantage of all these features, your computer needs a sound card and a video-capture board.

•Sound card: The sound card that comes standard with your computer will let you play music CDs and listen to audio associated with software, games and Web sites. Your genealogy software doesn’t need any additional hardware to create and play scrapbooks with sound.

You can even insert material from old audio tapes, such as interviews with relatives, in a scrapbook. First, you have to copy the audio tape to a hard disk. Just hook your tape recorder up to your computer with a stereo mini cable available at electronics stores. Record the sound from the tape to your hard drive using Windows Media Player or free software such as MusicMatch Jukebox <www.musicmatch.com> or Realjukebox <www.real.com/jukebox>. Then use your genealogy software to link the sound file to a person or family.

•Video-capture card: Before you can include a video in a scrapbook, you have to transfer the video clip from a camcorder or VCR to your computer’s hard disk. You’ll need an analog video-capture card to capture video from a traditional camcorder or a VCR.

buying new: A sound card adequate for most uses is a standard component of any computer system. For better-quality sound, buy good speakers and a subwoofer. Get an analog video-capture card if you want to use video from a nondigital camcorder or VCR on your computer.

Upgrading: Consider better speakers and a subwoofer for improved sound. If your computer has an open PCI slot, you can add a video-capture card for about $100.

For more multimedia tips, see the August 2001 Family Tree Magazine.

Dial-up or broadband Web access?

Since they’re mainly text with a few images, most genealogy Web pages display reasonably fast with a regular dial-up Internet connection. But with broadband (fast) Internet access, you can view even complex Web pages almost instantly, download software and GEDCOMs in seconds or minutes rather than hours and quickly exchange scanned photographs with friends or relatives. A broadband connection (DSL, cable or satellite) transforms the Internet from the “World Wide Wait” to a dynamic experience in which you can even view videos without waiting for them to download first.

DSL or cable provides Internet access from three to 50 times faster than dial-up access with a 56K modem. And a DSL or cable connection doesn’t tie up your phone line and is always on, so you don’t have to wait to connect.

Many areas still don’t have DSL or cable Internet service. Another option for high-speed Internet access, satellite, is available almost everywhere, but it’s more expensive.

•Dial-up: A 56Kbps(kilobits per second) V.90 modem is standard on new computers. Expect to pay about $20 or $22 a month for a dial-up account.

•DSL: Digital Subscriber Line service can be installed on your existing phone line. Check with your telephone company to see if it offers DSL in your area. Monthly fees range from $40 to $80. Installation varies — it’s typically $100 to $400, but some companies may offer it free or let you install it yourself.

•Cable: Your cable TV company will likely charge between $100 and $300 for installation and $40 to $50 a month for access.

•Satellite: Hughes Network Systems <www.direcpc.com> and StarBand <www.starband.com> provide satellite Internet access even if you live in the boondocks. Equipment and installation cost between $750 and $900 and the monthly fee is $49.99-$129.99. Check out Reviews.com for useful information and feedback.

Buying new: You should get an Ethernet network card in your computer so you’ll be ready for DSL or cable Internet access even if you don’t get it right away. A dial-up account is OK for moderate use, but consider DSL or cable if you plan to use the Internet very much. If you can’t get DSL or cable in your area, consider satellite service.

Sometimes new computers include a year of free dial-up Internet access. That’s a good deal, at least if you don’t have to change your e-mail address. But you might want to think twice about a rebate offer that commits you to several years of slow dial-up service.

Upgrading: For faster Internet access, switch from dial-up to broadband.

From the December 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT