Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In My Wild Irish Rose, a family history narrative I published in 2001 about the lives of my grandmother and great-grandmother, I stated that Delia (Gordon) Norris’ Irish origins were unknown. That book had been out about six months when, with help from friends, I finally broke through the brick wall and identified her place of origin. Did I publish that book too soon? Shouldn’t I have done more research until I found the place in Ireland? No. I had been searching for years to find Delia’s Irish origins, and nothing on the horizon indicated that an answer could be found in the near future; otherwise, I’d have put off publishing until I found it. When the book went to press, I was certain I’d have to search for several more years — if not the rest of my life — to uncover her origins. Sure, I could have waited to publish, hoping I’d find another lead, make another breakthrough; but then the book might never have been published. In some respects, writing and publishing your family history is a way to guarantee that you’ll break through any brick walls you may have — for it’s a cruel, ironic, Murphy’s law of genealogy that as soon as you publish, new information becomes available to you. But it won’t reveal itself until you publish.

Most family historians agree that research is the fun part. For some, just entering data into a computer software program is a sufficient and effective way to leave their genealogy for their descendants. But to sit down and actually write a family history is — OK, I admit it — scary. Besides, you’re sure your family will be enthralled with all those names, dates and places you’ve gathered, right? Unfortunately, I doubt it. If you don’t believe me, show your charts to a nongenealogist. Then time how long it takes before she politely smiles and hands the charts back to you. Now put a narrative account of a family history in her hands, and I’m certain you’ll get a different reaction.

Thinking like a writer

For many genealogists, putting on the research brakes is the hardest part of writing a family history. How do you know when you’re ready to stop researching and begin writing? Frankly, there’s always going to be another record to check, and as you begin writing, that’s when you really see any holes in your research. In fact, you might consider the first draft of your narrative as a way to find out if you’re ready to publish.

Here are two gauges to determine if you’re ready to turn off the microfilm reader and begin writing:

1. Have you searched every possible record for the family, including records that individual family members may have generated? These are the typical, obvious sources:

• birth, marriage and death records

• cemetery and funeral-home records

• church records

• city directories

• family histories and genealogies (what’s already been written about the family)

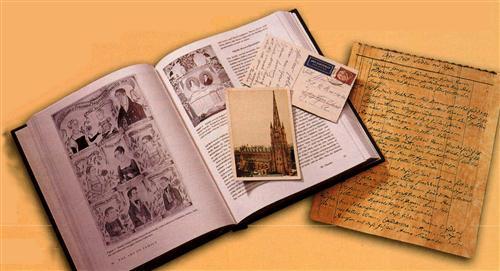

• family sources (such as Bibles, letters and diaries) and oral histories

• immigration records (naturalizations and passenger lists)

• land and tax records

• military service records, pensions and bounty-land warrants

• newspaper articles and obituaries

• nonpopulation censuses (agricultural, manufacturing and mortality)

• population censuses (federal, state, slave and Indian — for every census year that your family may have been recorded)

• probate and court records (wills, administrations and inventories)

If you haven’t searched for all of these records for each family or family member you want to write about, you’re not ready to write. That’s not to say that you have to find all of these records for each family member. If you’re dealing with a family that has been in America for generations, they might not have immigration records. If the family lived in a rural community, they may not be listed in a city directory. But certainly, you need to have checked for every possible record your family of interest might have generated.

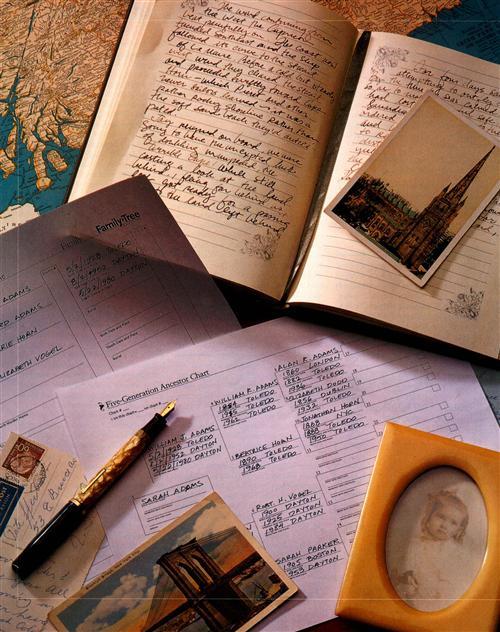

2. Have you turned your family group charts into “family summaries” to get the full picture? This is a crucial step toward pulling your data together into a family history narrative. So when you believe you’re ready to write, don’t bypass this step. A family summary should include:

• all genealogical facts you’ve gathered through your research (births, marriages and deaths, for example)

• your analysis of records and research, plus biographical data

• clearly identified speculations about why something happened, who someone’s parents were and so forth

As you write your family summary, go back through all the files and records you’ve gathered for the families you plan to write about and make sure you’ve included everything. It’s amazing how you’ll discover new things with a fresh pair of eyes. Once you’ve reviewed your files and compiled all of your research, analysis, and speculations for one family group into a family summary, review it for any additional genealogical research you still need to do.

Besides seeing holes in your research, you may find topics you want to explore in more detail as you transform sterile facts into narrative. Mark sections in the text for further study. For example, if you discover that one of your ancestors suffered from tuberculosis and you’d like to learn more about the disease, highlight tuberculosis as a reminder that you want to research that topic.

Before beginning your family history narrative, you need some direction. Where do you want the story to go, and what do you want to say? If you read a lot of fiction or watch a lot of movies, you’ve probably realized that there are only so many basic story plots. Ronald B. Tobias identifies 20 of them in his writing guidebook, 20 Master Plots (Writer’s Digest Books). Plot involves the reader in the game of “Why?” The plot reveals conflicts and resolutions for the characters. We keep reading because it’s clear a conflict exists, and we want to see how the plot unfolds and how the characters will resolve their problems. I’m sure you’ve heard the saying “The plot thickens.” It thickens as twists and turns are added to the story.

In your family history, your ancestors are the characters. What problems did your ancestors have to resolve? Who or what stood in the way of an ancestor’s success? Think about the four basic conflicts: man against man, man against nature, man against society and man against himself. Which of those four conflicts underlies the plot in your family history? Then, how will you reveal the plot to your reader? Consider these six common family history plots:

• Immigration: Most of us have immigration plots in our family histories. Indeed, many published genealogies begin with the immigrant ancestor. Instead of just recording the facts about an ancestor’s immigration to America, think about the obstacles or problems your ancestor had to resolve. I can guarantee your fourth great-grandfather from Ireland didn’t wake up one morning and say to his wife, “Bridget, pack your bags. We’re going to America this afternoon.” Deciding to leave their homeland and relatives may have been agonizing. If your own family lore doesn’t reveal the problems encountered or the solutions devised by your immigrant ancestors, consider the experiences of other immigrants who came from the same country or area at around the same time period. Remember, you’re not going to fictionalize; you’re going to research what might have happened and speculate on the possibilities.

• Pioneer saga: Just as most American families have stories with an immigration plot, many of us have stories about migration. Rare are the families who came to America and settled in one spot for generations. Migrating westward and moving to the wilderness are common plots in family histories. What did the move entail? What was it like along the trail? How did the family build their house? How did they clear the land? As in many immigration stories, the women may not have been keen on the idea of leaving their families behind. Many didn’t want to go. How did they cope? What was it like to raise a family on the frontier? There’s a lot to explore in this plot.

• Rags to riches: Or in my family’s case, riches to rags. Your ancestors may have been dirt poor, but with each new generation, the family prospered. Or, maybe your ancestors were like my Colonial Virginia people, who had acres upon acres of land, then lost it in the Civil War or from dividing it among generations of heirs. Again, people don’t wake up one morning and decide to be rich (or poor). Circumstances, events or people helped them make their decisions or got in their way. What happened in your family history?

• Rising out of slavery: This, of course, is a common plot for African-American writers, and it’s been so widely researched and written about that you already should have ideas about the obstacles your ancestors faced. Do the records you’ve uncovered reveal anything specific or out-of-the-ordinary for your family? Will you have to deal with issues of miscegenation (mixed-race marriages or relationships)? How did your ancestors overcome the biggest obstacle for humankind?

• War and military survival: Family historians seem comfortable writing about the war or military-service experience for their male ancestors. But what problems did the soldier’s wife and family face while he served his country? Look at the whole picture, not just half of the story. Remember that during a war, most men spent more time either in camp or sick than in battle; you can describe those experiences. If your ancestor was a prisoner of war, you’ll have even more obstacles to write about.

• City dweller to country dweller: Or vice versa. If you have ancestors who left a city in the East or South to settle on the Western frontier, they had quite a few adjustments to make. Think about what it must have been like to leave the neighborhood dry-goods store far behind, to have to live off the land. We know from letters and diaries that most women had no choice in moving to the desolate areas where their husbands wanted to settle. How did they cope with their new environment? What challenges did they face in the course of everyday survival?

Don’t worry about whether your plot is original; the important thing is to make sure you have one. What makes your family history different from another one with the same plot is the characters, events and the way you isolate and develop themes.

Revisiting genealogical resources

Now that you know what type of family history you want to write, can you weave a compelling story from the facts you’ve gathered? At the beginning of this article, I listed genealogical sources you should have checked before writing your family history. Now, let’s revisit those sources for broader information that could provide additional details for your narrative.

You’re no longer looking for the who, when and where: the names, dates and places specific to your ancestors. You’re now looking for the why, how and what: broader information that explains why things were the way they were, how something happened and what life was like. This is what will put flesh on the bones of your narrative.

Take a second look at vital records, for instance. Traditionally, genealogists record the facts from births, marriages and deaths, but family history writers need to look at them in a broader light. Find out who the marriage witnesses were. What relation, if any, were they to the couple? If the couple was married in a church, give us some details J about that church or religion.

Find out what your ancestor died of. Was it a lingering disease such as tuberculosis (consumption)? What would it have been like for your ancestor to die of that disease and for his family to provide care in the final stages of the disease?

In the cemetery, you’ll want to take a broad look at your ancestors’ final resting places. Besides noting who was buried in nearby graves (in case further research reveals a relationship), also note artwork and symbols on your ancestors’ headstones. Do these reveal memberships in organizations popular in your ancestors’ community? By the type of headstones, you also can tell if the community was well-off or economically depressed.

You can ask loads of other questions about your ancestors and their old stomping grounds: What was the terrain like? What events shaped the area while your ancestors lived there? What folk celebrations, such as county fairs or barn raisings, did people attend? Is there information about an organization your ancestors belonged to? What impact did various wars have on your ancestors’ community?

You can find answers to these questions in local and county histories. Rather than looking for your ancestors’ names, your goal this time is to gather information on the places your ancestors lived. For general statistical information about your ancestral country, visit the CIA’s World Factbook Web site <www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook>. It provides a map and general data about geography, government, economy, communication, transportation, and military and transnational issues.

Scoping out Social Histories

As you take a second look at genealogical sources, see if any of the documents will directly or indirectly answer your questions about daily life, motivation and behavior. You can broaden the background research even more by consulting social histories.

Maybe your ancestor didn’t leave an account of his or her daily life, but someone who lived during the same time period, in the same locality, probably did. Social historians draw on these accounts (letters, diaries, family papers) and genealogical sources (probates, censuses, land records and so on) to learn about the experiences of people in a given time and place. They look at a community or society as a whole, whereas we genealogists usually focus on individuals and specific families. From social histories, we can determine the typical experiences of people like our ancestors.

You can find social histories covering just about every topic you need to research and write about in your narrative (see box, page 49). When you find a social history that covers your topic of interest, check that book’s bibliography for additional sources.

To find social histories, start by checking online library catalogs (such as the Library of Congress catalog <catalog.loc.gov>) and online bookstores. First, categorize your ancestors by ethnic group or occupation. Then, in the computerized library catalog, type your ancestor’s category, followed by social life and customs. For example, if you want to know what life was like for your Boston Irish ancestors, type Boston Irish social life and customs.

To help fill in the details of your ancestors’ daily lives, turn to books such as these:

• Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer (Oxford University Press)

• Domestic Revolutions: A Social History of American Family Life by Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg (Free Press)

• Everyday Life Among the American Indians by Candy Moulton (Writer’s Digest Books)

• Everyday Life During the Civil War by Michael J. Varhola (Writer’s Digest Books)

• Everyday Life in the 1800s by Marc McCutcheon (Writer’s Digest Books)

• Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650-1750 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (Vintage Books)

• Home Life in Colonial Days by Alice Morse Earle (Berkshire House)

• The Uncertainty of Everyday Life, 1915-1945 by Harvey Green (University of Arkansas Press)

• Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 1876-1915 by Thomas Schlereth (HarperCollins)

While social histories will be the mainstay of your background research, you may want to explore several other resources. Perhaps nothing will give you better insight into how your ancestors lived than books, magazines and newspapers from your ancestors’ day. If you’re researching an ethnic group, cookbooks and food histories can provide you with cultural background about both the old country and ethnic communities in America. If you love to read novels, historical fiction can give you not only insight into a time and place, but also ideas on how to craft your family history narrative.

ADVERTISEMENT