Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

With superheroes everywhere from the box office to toy shelves to Happy Meal boxes, it’s hard to believe that what future pop-culture historians might call the “superhero age” began just 70 years ago. And even then, the rest of the world wouldn’t thrill to the exploits of that “strange visitor from another planet” — Superman, the archetype of all today’s costumed do-gooders — for another five years.

In 1933, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were just two Cleveland 19-year-olds. Enamored of comic strips and science-fiction novels, they dreamed up their own creation combining the two. A Chicago publisher expressed interest but ultimately rejected their “Superman” idea. Crushed, Shuster burned all his artwork except the cover.

A year later, as Siegel struggled to sleep in the city’s summer heat, he had an inspiration: What if Superman had come to earth from a dying planet, launched here as an infant to save him? And what if this “man of tomorrow” led a double life, hiding his abilities behind the glasses and mild manner of reporter Clark Kent?

In a 1983 reminiscence, Siegel would explain, “Clark Kent grew not only out of my private life, but also out of Joe Shuster’s. As a high school student, I thought that someday I might become a reporter, and I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t know I existed or didn’t care I existed. So it occurred to me: What if I was really terrific? What if I had something special going for me, like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that?”

Come morning, Siegel ran the 12 blocks to his pal’s apartment and breathlessly poured out his new concept for the character. Together, they crafted the hero’s uniform — Siegel suggesting the S on the chest and the cape, Shuster drawing the rest. And again, they hit the bricks to peddle their creation.

They must have been men of steel to survive the rejections that followed: “We are in the market only for strips likely to have the most extra-ordinary appeal,” replied Bell Syndicate, “and we do not feel Superman gets into this category.” United Features deemed their work “rather immature.”

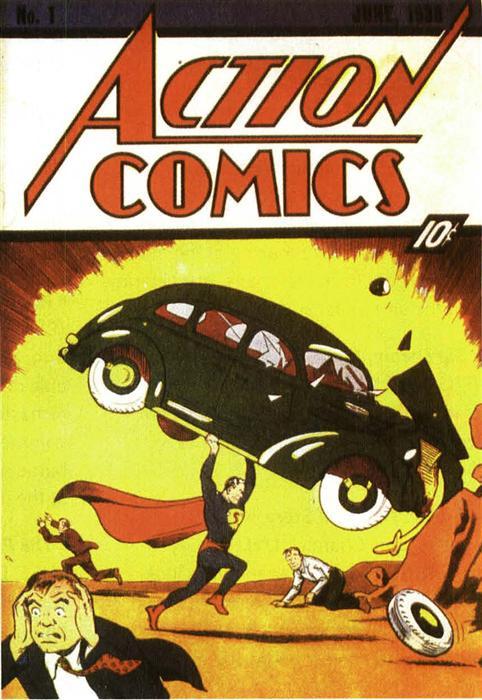

Finally, in 1938, DC Comics was launching a new title, Action Comics, and had pages to fill. Almost as an afterthought, it gave Superman a try. It was “better than nothing,” figured publisher Max Gaines, who paid the boys $130. Though Superman appeared on the cover of the first Action Comics, it wasn’t until issue 19 that he became a cover fixture — as he has been there, on his own Superman title and around the world for more than 60 years.

Siegel and Shuster would later battle in the courts for the rights to Superman and Superboy, never entirely winning the recognition or the riches you’d expect for the creators of arguably the 20th century’s most widely known fictional character. Shuster died in 1992, Siegel in 1996.

There were other mighty heroes before Superman, of course — Siegel acknowledged his debt to Philip Wylie’s novel Gladiator, and the teens lapped up Doc Savage, Flash Gordon and the Shadow. Other heroes even had secret identities, way back to the Scarlet Pimpernel. But none so successfully combined these notions with the four-color exuberance of a muscleman in tights and cape, fired by the adolescent longing to be not merely ordinary but, well, super.

Last year’s Spider-Man movie sensation triggered a stampede of heroes to the screen in 2003 — Daredevil, the Hulk, an X-Men sequel. On television, the Superman story is being reimagined, sans cape and tights, in the WB network’s “Smallville.” There’s talk of another Superman movie.

All owe a debt to two Cleveland teens who imagined leaping tall buildings in a single bound. From 70 years later, we can see that they flew much higher than even they had dreamed.

From Family Tree Magazine‘s March 2003 America’s Scrapbook.

ADVERTISEMENT