Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

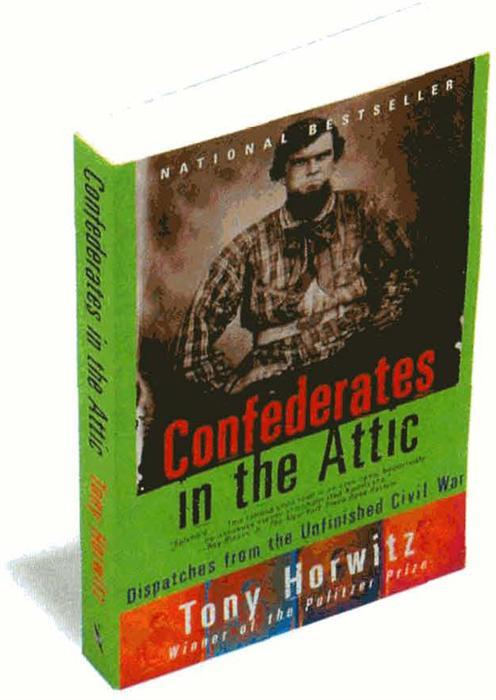

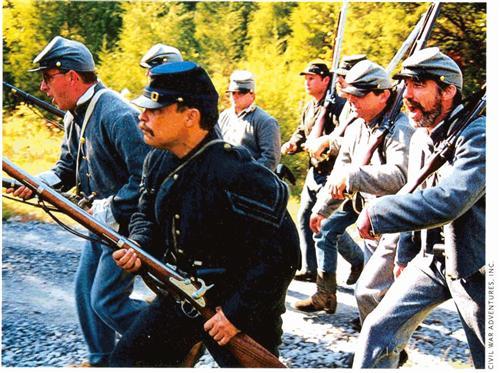

In his best-selling book Confederates in the Attic (Vintage), Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and war correspondent Tony Horwitz discovers one of America’s favorite new pastimes — Civil War reenactments. This hobby carries getting a feel for your ancestors’ lives to an extreme: joining the ranks of the cold and uncomfortable for a weekend, gnawing on beef jerky and soaking uniform buttons in urine for an “authentic” look. After participating in a reenactment weekend himself, Horwitz couldn’t help wondering about the appeal of re-living such an unpleasant period in history. The answer, as Horwitz shares in this Family Tree Magazine Q&A, isn’t so simple.

Q. Why are Civil War reenactments so popular?

Reenacting reflects a populism that’s come into history People are much less interested in great leaders, for instance, than they were 20 or 30 years ago. If you went to a Civil War roundtable 30 years ago, likely they’d be talking about Lee and Grant and Stonewall Jackson. And they still do that, but people are just as interested now in the average soldier. Their own great-grandfather was more likely an average private, not a grand figure. It’s this desire to get your hands dirty to do the history yourself, to bring it down to the popular level. One thing that reenactors will always tell you is, “We’re here to remember the experience of the common soldier, North and South.”

Q. Why do many Americans remain so intrigued by the Civil War?

One reason it lingers is that many of the issues at stake in the war are still unresolved. Race is still at the center of our national debate, states’ rights is still a very vibrant political philosophy, and even the largest question posed by the war, “Are we one nation?” is still relevant. It’s not a regional question anymore, but we’re sometimes asking ourselves, “Are we a bunch of angry interest groups and ethnic groups and gender groups in a sort of unhappy marriage of convenience?”

We are a nation with fissures. We’re lucky now with the economy going as well as it is that we’re going through a period of mellow feelings. The racial divisions and other things we’ve had in the past are less acute at the moment, but I don’t think they’re lingering far beneath the surface.

Q. How would you compare Americans and their feelings about the Civil War to other countries where you’ve worked as a war correspondent?

I don’t think Americans are really comparable to others I met overseas who are still agonizing over historical conflicts. Given how many Americans died in the Civil War — two percent of the population, equivalent to 5 million people today — and how the South was devastated socially and economically, it’s remarkable how quickly we’ve reconciled and for the most part left the conflict behind. I think our continuing passions over the Civil War are remarkable when you compare them to our attitude toward the rest of our history (which we tend to forget), but they aren’t striking in a global context, where people often nurse historic grudges for many centuries.

Q. Are re-enactors trying to get in touch with the history of the United States, or are they more interested in learning about their personal ancestry?

I think they’re more interested in their ancestors. I think there’s almost an ancestor envy at work among a lot of people who have immersed themselves in their genealogy. We live in a time that’s wonderfully prosperous and secure in the 1990s, but it lacks a certain drama.

And I think people look back to this period as being somehow larger than life, where people were living and dying for a cause. And that’s why it’s so bewitching, and people try to travel back to that time through genealogy, through trying to get to know their great-grandfather and what he did, or the women.

It reflects a search for meaning, a search for roots. We live in a time when we feel alienated from the landscape, sometimes alienated from each other. People move so much, people change jobs. It’s a way of connecting, to understand why you’re here and feel some stronger tie to America and your landscape.

There’s also a natural cycle that occurs. I don’t think it’s an accident that we’re so interested in World War II now; it’s about 50 years after the event. The high tide of Civil War remembrance was about 50 years after the war. It’s when the veterans themselves start to die off that people think, “My gosh, let’s honor this generation.” When we look at {war veterans], we see people who seem nobler than ourselves, who made real sacrifices. Somehow they were tougher than us. They had these antique American virtues of stoicism and self-reliance that perhaps we’ve lost in the late 20th century.

PAGE-TURNER FROM THE PAST

Maybe Mary Higgins Clark had better start researching her family tree. Publishers Weekly, the bible of the book-publishing industry, seems to be heralding a new subgenre of thriller novels: the “genealogical thriller.” In its review of romance novelist Brenda Joyce’s new book, The Third Heiress (St. Martin’s), PW predicted that the page-turner with a family-history plot could be Joyce’s breakout novel.

The thriller follows heroine Jill Gallagher, a ballerina-turned-Broadway-dancer, after her aristocratic British fiance is killed in a car wreck. Accompanying his body back to London, Jill finds a mysterious 1906 photo of two women: her fiance’s grandmother and another young woman with the same last name as Jill. From there Jill is off on a quest into her past, searching for the secret of the woman she’s convinced is her ancestor. Of course, there’s lots of intrigue, betrayal and romance along the way.

For more on author Brenda Joyce, see her site on the Web at <www.brendajoyce.com>.

The Great Web Traffic Jam

How do you handle a million Web users? That was the challenge for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when it unveiled its new FamilySearch genealogy site, <www.familysearch.org> in late 1999.

The church’s Web site planners and their technology partner, IBM, had anticipated first-day traffic of maybe 120,000 visitors. But by 8:30 in the morning on May 24 — half an hour before the official launch — the number of hits put the site on a pace for 300,000 users. By day’s end, 400,000 users had logged on — and an estimated 600,000 more had tried and failed to get through one of the Web’s worst traffic jams ever.

The site managers dealt with the gridlock with the computerized version of crowd control. “When you go to a restaurant, there are only a certain number of seats,” site software developer Justin Lindsey of LavaStorm explained in the computer trade journal InfoWorld. “You have to make sure you take care of the people in the seats and get to the people in line as fast as you can, and that’s exactly what we did…. We’d recognize you as coming from a particular location and put you in pool A or B and say ‘We’ll serve you in 30 minutes and you’ll get 30 minutes on the site.’”

That daily rate of 400,000 users would put FamilySearch 10th in site traffic on the whole Internet, according to Web ratings measured by Media Metrix <www.mediametrix.com>. At a million users (and would-be users) daily, the site would be the number-one most-visited on the Web.

Traffic has since settled down to a still-impressive 200,000 users per day. Upgrades will enable the site to handle about 450,000 users without a logjam.

DID I EVER TELL You YOU’RE MY HERO?

While your grandpa or your great-uncle Irv probably don’t have a shot at being Time’s Man of the Year, they can be honored as a “Family Hero” over at competing Newsweek. The newsweekly is spinning off its popular “My Turn” column into a “My Turn: Family Heroes” Web site that invites readers to submit tributes to “the most influential person in your family from the 20th century.”

To honor your own family’s hero, just submit a 500-word essay and photo for screening by Newsweek’s editors. Accepted entries will be posted on the site as a personalized page, complete with its own Web address. The best submissions will be spotlighted weekly on Newsweek’s Web site, <www.newsweek.com>, and two will be published in the magazine in December.

For more information, see <myturn.newsweek.com>. Entries will be accepted only through Dec. 31.

Eating Like the Good Ol’ Days

For many of us, memories of growing up revolve around food. But our fondest recollections are of food that, well, we can’t eat anymore: grandma’s brownies, mom’s pound cake, grandpa’s fried chicken … all are delicious, calorie-packed, fat-filled flavors of yesteryear. And they’d better stay in yesteryear unless you want to put on 20 pounds and have a coronary, right?

To the rescue comes Jeanne Jones and her new cookbook, Homestyle Cooking: 200 Classic American Favorites (Prevention Health Books). Jones “guarantees” to make two grams of fat taste like 10 in her reformulations of such family-heirloom favorites as Tuna Noodle Casserole, Macaroni and Cheese, Cherry Pie, Meat Loaf and Turkey Tetrazzini.

Taste buds intrigued? Contact Rodale Cookbooks, 33 E. Minor St., Emmaus, PA 18098, (800) 914-9363 for ordering information.

Back to the Future forY2K

“He tripped over the Y2K dilemma not in looking forward to 2000 but in working backward to 1800 and 1700.”

It figures that one of the earliest warnings of the Y2K computer glitch would have come from genealogy research. Computer pioneer Bob Berner, 79, first raised a red flag about many computers’ inability to distinguish “2000” from “1900” — because they were programmed to use only the last two digits in calculating years — when helping the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with its genealogical record-keeping. But he tripped over the Y2K dilemma not in looking forward to 2000 but in working backward to I800,I700 and so on. When a computer uses only two digits to represent a year, “1856” and “1956” are both “56” — a serious problem for family historians.

Berner was part of a group in the 1950s that developed COBOL, one of the first computer-programming languages. He’s also considered the “father” of ASCII, the system computers use to represent letters and numbers in digital form.

ADVERTISEMENT