Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In this article:

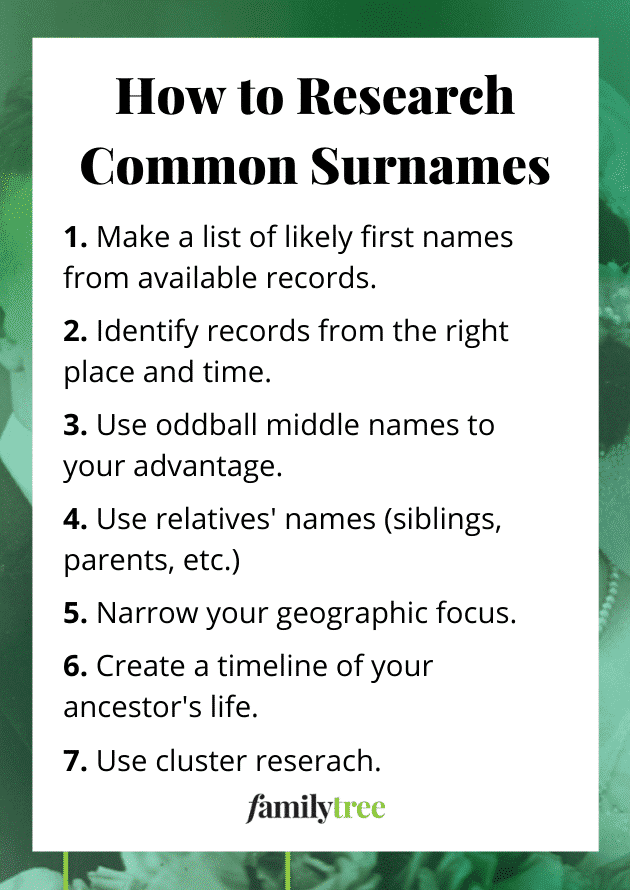

When You Don’t Know the First Name

Using Middle Names

Using Relatives’ Names

Narrow Your Geographic Focus

Create a Timeline

Use Cluster Research

Make Use of Misspellings

Case Study: Emily Brown’s Ancestors

Related Reads

Fans of 1970s Westerns might recall a TV series titled “Alias Smith and Jones,” in which a pair of outlaws try to go straight. To keep a low profile and earn a promised pardon, they adopt as pseudonyms two of the most common surnames in the country.

If your own genealogy “most wanted” ancestors have similar surnames, this Old West yarn might feel painfully familiar: Finding folks named Smith and Jones—or Brown, Williams, Miller or other all-too-common surnames—can be like trying to identify a single steer in a cattle drive.

You might think that, with a last name like “Fryxell,” I’d have no worries about too-common surnames. (In fact, I even wrote about researching ancestors with uncommon last names.) But inevitably, even the most exotically named families have Smiths and Joneses in their roots. My mother’s family were Dickinsons, and a few generations back I run into Browns.

My and my wife’s Scandinavian ancestors share innumerable Anderson, Johnson, Erickson and other -son and -sen patronymic surnames. My family files are full of names like “Ole Anderson”—all separate people, many of them not directly related.

So if there’s no escape from the curse of common surnames, is there hope for separating these ancestors from the herd? Before you resort to putting up wanted posters for your own John Smith and Mary Jones, try these strategies.

Work Around Missing First Names

The worst-case scenario for an ancestor with a common surname is, of course, not knowing the first name. How can you pick your Miller out of a zillion Millers living in roughly the same place and time?

Find Likely Candidates

Before you start drowning your sorrows with sarsaparilla, try to identify some candidate given names you can at least test against available records. A father might have the same name as one of his sons, for example, or one of his grandsons.

Many ethnicities have common naming patterns that can provide clues. In Italy, for instance, the first daughter was often named after the father’s mother; the second daughter, after the mother’s mother; and the third daughter, after the mother. In the American South, the mother’s maiden name might become a child’s first name (Oglesby Miller, for instance).

Identify Possible Record Matches

You can also work in the opposite direction, identifying records in the right place and time and trying to match those names to your ancestor. This often works with land records, which typically include several names (such as those of neighboring landowners). If you find a Thomas Miller in a land record that also mentions your Mystery Miller’s known future in-laws, see if you can prove Thomas is your ancestor.

For example, my fourth-great-grandmother had the all-too-common name of Mary Phillips. I had no first name for her father, but I did find a 1791 land record in Georgia listing her husband, George Clough, and several others—including a Joseph Phillips. Having at least a name to test, I set out to see whether Mary’s father could be Joseph (or one of his brothers who I discovered in the same time and place).

Use Middle Names

Obviously, your manhunt will be much easier if your common-surnamed ancestor has an unusual first name. Rounding up Josephat Johnson will be a snap compared to picking the right James Johnson.

No such luck? Maybe your ancestor at least has a distinctive middle name. It might be unusual—James Tiberius Johnson, if his parents had a fondness for ancient Rome. Or the middle name (like some first names) could echo the mother’s maiden name or some other family name.

The rub here is that so many records neglect to include the individual’s middle name, or give only an initial. Vital records, especially at the start and end of life, are most likely to give a full name, although tombstones rarely have enough room. If you do spot a record with a notable middle name, however, make a note—this might be what separates your ancestor from the herd.

Research with Relatives’ Names

Even if your ancestor has a given name as common as his surname, he might have a relative with a happily unusual first name. If John Dickinson has a sister named Olhtina, for example, you can use that fact to trace their family backwards in the census. Search for Olhtina instead of John, and the John you find in her childhood household will be your man.

With a little luck, this trick can also help sort through vital records. If your ancestor Jane Jones had a brother or cousin named Odysseus, the marriage record where Odysseus Jones is a witness is almost certainly the right one. Godparents with odd first names can similarly identify the correct baptismal record, if those individuals are relatives or otherwise associated with the family in other records.

If confronted with three similarly timed death certificates for a William Brown, check who witnessed his demise. If it was a colorfully named daughter named Louisiana Brown, you’ll know that’s your man. Even cemetery records can contain such clues: Look for family members buried in nearby plots; the final resting place of Susquehanna Smith will flag the entire family as yours.

Narrow Your Geographic Focus

Geography is often as important as chronology in family-history research, and never more so than when dealing with all-too-common surnames. But simply rounding up all the Smiths in a county seldom suffices to single out your ancestor—you may need to narrow your geographic focus.

Old maps can be helpful here, as can sites like the USGS’ Domestic Names search. If you can identify the township or other specific place your Smith family lived, you can zoom in on the Smiths’ records in that locale. It’s certainly not impossible for an ancestor to generate records on the other side of a county (or across the county line), but researching common surnames often requires playing the odds.

My Dickinson ancestors, for example, lived in Cumberland and Moore Counties in North Carolina during the period I was trying to sort them out. The location of a family graveyard gave me two more specific places—Bear Creek and Deep River. A will gave me another key waterway, the Little River. Now I knew to pay attention to any Dickinsons with ties to those locations; other Dickinsons could be back-burnered.

Create a Timeline

Creating a timeline of ancestral events can also help you round up the right common-surnamed kin. Write out a chronology of what you already know about your target family—some genealogy software programs will generate one for you. Try to fit the records you’ve found into this timeline. Here again, land records can be useful in locating individuals in time and place; even though these records seldom contain the vital facts you want to fill in on your tree, don’t overlook them!

If you know that your Johnsons were in Abilene in 1876, the Joe Johnson you found in Deadwood that same year is unlikely to be an ancestor. On the other hand, a marriage record from roughly that time and place might be a match.

This strategy can also help separate same-named individuals. Not even the trickiest ancestors can actually be in two places at the same time! I used this approach to sort out my Dickinsons, who had the unfortunate habit of reusing a small cluster of first names. “My” Robert Dickinson had temporarily departed for South Carolina in the 1770s, which matched another account of his son Michael Dickinson being born there in 1776. That singled out the 1776 Michael from four other individuals with the same name. One of them turned out to be the brother of my ancestor Robert Dickinson (both sons of yet another Robert), while two other Michaels were sons of two different Willis Dickinsons. Without a timeline, I never could have puzzled out who was who.

Use Cluster Research

Regular readers will be familiar with the classic concept of “cluster” genealogy. Think of the Old West icon of the wagon train, in which multiple families traveled together to new homes. Since our ancestors tended to migrate in groups with cousins and neighbors—whether in wagon trains or less formal aggregations, sometimes spread out over time—you can use these “clusters” to trace them. It’s an especially useful technique for following ancestors with common surnames, since (with any luck) not everyone in their cluster will be named Smith or Jones.

If you’ve identified an ancestor in a census, for example, make sure to note other names on the page. Look not only for nearby enumerated relatives, but also for neighbors whose names might crop up in the census 10 years earlier. If these cluster candidates happen to have less-common names, all the better. When you can’t lasso your John Smith, you can use his neighbor Josiah Crumplebottom to pick him out in the prior census.

For example, imagine the challenge of identifying the right John Johnson in Illinois in the 1910 US census. A quick Ancestry.com search results in 25,343 hits for “Exact” matches, with another 50,000 or so other possible matches. If you knew, however, that John’s sister Christina had married my great-great-uncle Charley Fryxell, you could search for her instead—and discover John Johnson living right next door. The Johnsons and Fryxells had migrated as a cluster from the same village in Sweden to Rock Island County, Ill., where they could still be found together some 25 years later.

Search with Misspellings

Yes, even common surnames can be misspelled in records—or vary over time and between branches of the family. My Dickinsons variously appear as Dickerson, Dickeson and Dickinsen, and I make it a habit to check for all these as well as the truncated Dixon. If none of the Mary Johnsons you’ve found in roughly the right time and place pans out to be your ancestor, consider the possibility that she’s listed as Mary Jonson, Jonsson or even Jansen.

It’s also possible that a spelling variant can help you spot a common-surnamed ancestor, if for whatever reason that twist persisted in other records. Sometimes a family might opt to be different, whether by chance or to stand apart from black-sheep kin. One of my family stories has it that Great-great-grandma added an E to their Low surname simply because it “looked fancier.” If you come across this kind of permanent “misspelling,” seize on it and celebrate the fact that your common-surnamed family is suddenly not so common anymore.

Case Study: Emily Brown’s Ancestors

Many of these strategies and tricks come together in my search for the ancestors of my great-great-grandmother, who not only had the all-too-common surname Brown but an equally ordinary first name: Emily. How could I find her family amid a whole bunch of Browns?

Fortunately, Emily had an unusual middle name—Few, derived from her mother’s maiden name. Her mother had an even more unusual first name, Lodoiska. So it wasn’t too difficult to demonstrate that Lodoiska Few married Augustus J. Brown. (That “J,” whatever it stood for, would help differentiate Augustus, too.)

Estate records revealed that Augustus’ father was named Ephraim—a first name that would repeat, helping to trace the family all the way from Alabama to Maine. Ephraim’s father had the too-common name of Daniel Brown, but Daniel’s father in turn was named—you guessed it—Ephraim. (This elder Ephraim also had a son named for him, whose colonial military career helped pinpoint the family in Maine and Massachusetts.)

The family’s move from Massachusetts to what later became Maine gave me some pinpoints on the map that further helped separate them from other Browns in New England. I knew to look for Brown records in Brunswick, Maine, and before that in Salisbury and Amesbury, Mass. I also sketched out a timeline to make sure the birth, marriage and death dates I discovered were all plausible.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, May 2023.

Related Reads

Pin It!

ADVERTISEMENT