Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Written by Sunny Jane Morton, unless otherwise noted

Jump to:

Mortality Schedules

American Indian Censuses

Agricultural Schedules

Manufacturing and Industry Schedules

Slave Schedules

Veterans Schedules

Defective, Dependent and Delinquent Schedules

Social Statistics Schedules

Special US Census “Fast Facts”

Every decade since 1790, the federal government has taken a census of US residents. Its population schedules are core genealogy records, among the first you use to find your family. But there’s a lot more to the federal census than just population schedules.

Several US censuses included extra lists detailing certain populations. Depending on the year, you might learn details about the recently deceased, slaveholders and the enslaved, military veterans and their widows, farmers, manufacturers, Indians, the disabled, and those in institutions or prisons.

Why Should I Use Special US Census Records for Research?

The chances of a given ancestor fitting one of these qualifications may seem small, but if you’re researching at least one US line between 1810 and 1940, it’s worth looking for the unique information special schedules provide. They can enhance your knowledge of your relative’s economic well-being, occupation, health, military service and more. What you learn also may provide clues to point you to additional information in the records of cemeteries, prisons, county homes, hospitals and the military.

Though not all schedules survive, many that did are available online. Some were distributed back to individual states or to any archive that would take them, making them more difficult to locate. This guide will familiarize you with special censuses, the information they contain and how to find them.

1. Mortality Schedules

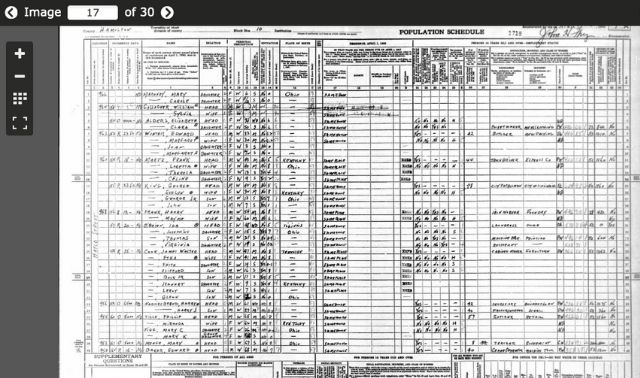

For decennial censuses from 1850 to 1900, enumerators logged deaths that occurred in the year preceding the census date of June 1. Some deaths outside that time frame were reported, too. The resulting mortality schedules survive for some portion of at least 75 percent of states for 1850 to 1880, as well as the 1885 state/territorial censuses. While mortality schedules didn’t capture every death, they still represent a strong nationwide cross-section in the days before death records were generally created.

Record content

Mortality schedules requested the deceased person’s name, gender, age, color, widow(er) status, birthplace, death month, occupation, cause of death and length of illness. In 1850 and 1860, this may include enslaved African-Americans, who otherwise don’t typically appear in censuses. In 1870, parents’ birthplaces were added. The 1880 schedule also noted where a disease was contracted and length of residence at that place.

Access

Start your search in the Ancestry.com subscription database of 1.6 million records from mortality schedules (it’s also on HeritageQuest Online, which your library might offer). Ancestry.com has an overlapping index for 1850 to 1880, without record images. FamilySearch.org and Findmypast have 1850 mortality schedules.

MortalitySchedules.com has a directory to indexes or transcriptions by county. Original schedules are scattered across state repositories and the Daughters of the American Revolution library. Look for microfilmed records at the Family History Library (FHL) by doing a Places search of the FamilySearch Catalog. Enter the state and check the Census or the Vital Records category.

- Indented first names with ditto marks indicate this person has the same surname as the person listed above. Deaths were listed in household order, so these individuals are likely from the same family.

- Note the deceased’s age at death, gender, race, free or slave status, married or widow status and birthplace.

- The 1850 population schedule doesn’t name enslaved individuals, but they’re named here in the mortality schedule. Only thee slaves’ first names are shown; they didn’t have legal surnames.

- The deceased’s month of death, cause of death and number of days ill are listed.

- Alexander Hall died from a sudden accident. His is the only occupation noted on the page; perhaps he was a well-known businessman. For these reasons, look for a report of his death in local newspapers.

2. American Indian Censuses

American Indians were generally excluded from the US federal census before 1860, and in 1860 and 1870, enumerated only when they didn’t live on a reservation. The 1890 census enumerated all Indians on the population schedules, but most of these are lost, except for the Cherokee Nation population schedule. But in some years, enumerators gathered additional information on them in special schedules.

Record content

In 1880, a Special Census of Indians was taken in unsettled areas and on reservations in California and the territories of Washington and Dakota. A two-page form for each family lists the tribe, reservation and household members with Indian and English names, age, gender, relationships, marital and tribal status, language(s) spoken and work, health, literacy and property ownership.

Beginning in 1900, censuses counted Indians regardless of where they lived. In 1900 and 1910, special Indian schedules noted tribal affiliation (for self and parents), mixed blood percentage, whether polygamous, US citizenship status, and whether living in a movable or permanent home.

Access

Search the 1880 Special Census of Indians on Ancestry.com. Originals are at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

The surviving Cherokee Nation (Indian Territory) population schedule is published in The 1890 Cherokee Nation Census Indian Territory (Oklahoma) by Barbara L. Benge (Heritage Books). Look for special Indian schedules in the 1900 and 1910 US censuses at the end of the county’s population schedules, or grouped together at the end of the state’s population schedules. You’ll need to browse in online collections. If you don’t find them, check the same places on microfilmed censuses at major research libraries.

Search several Indian Census Rolls on Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online. You also can access these rolls from NARA.

3. Agricultural Schedules

The early United States was a land of farmers. Starting with the 1840 census, the government assessed national production on agricultural schedules: which crops and livestock were being raised, where and by whom. Though some schedules were destroyed after statistics were compiled, agricultural schedules survive for 1850 to 1880 and an 1885 territorial census. They offer rich details on farmers’ livelihood during a time of dramatic change in the business of growing food.

Record content

Schedules for 1850 and 1860 list farmers and plantation owners who produced at least $100 in farm goods annually. In 1870 and 1880, they listed farmers who planted on at least three acres and/or produced $500 or more in farm goods. Landowners, tenant farmers and sharecroppers weren’t distinguished on the schedule until 1880.

Schedules in 1850, 1860 and 1870 list the owner/manager/agent, acreage (improved and unimproved), value of property and equipment, and the amount, value and description of livestock and produce. In 1880, you’ll learn statistics on the farm’s paid labor force. This makes schedules of interest to descendants of those who ran farms and those who worked on them, if you know for whom your ancestor worked.

Access

Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online have some indexed images of agricultural schedules. If your ancestor’s locale isn’t included in these sites, try running a web search with the state, county, year and keywords census “agricultural schedule.” This might turn up originals at a state repository or university library. NARA also has some schedules on microfilm. If you end up browsing unindexed schedules, keep in mind they’re arranged by state, then county, then city or township.

4. Manufacturing and Industry Schedules

Seven censuses taken in the 1800s collected data on manufacturing or industrial firms that produced goods of a minimum value. Data—and what’s survived—vary by year.

Record content

In 1810, enumerators asked three simple questions about the nature, value and amount of goods, but most of these schedules were lost. In 1820, schedules added the business location, capital invested, machinery used and number of employees.

In 1850, 1860 and 1870, businesses with greater than $500 in annual production were listed on industry schedules. The same questions were asked each year: name of business and business owner; amount, kind and value of products; capital invested; nature of raw materials, facilities and machinery; average number of male and female employees and their wages. (Look up the schedule entry for an ancestor’s employer, if you know who it was.)

The 1880 manufacturing schedule asked similar questions about raw materials, labor, machinery and products for industries like mining, mills, brick and lumber production, food processing plants, textile producers, iron and steel, shipbuilding and fisheries. There’s also industrial data in the 1885 state/territorial censuses for the states of Florida, Nebraska and Colorado, and the territories of New Mexico and Dakota (not every state participated in this census).

Access

Surviving data for the 1810 agricultural census is included with the 1810 population schedules. You can browse for these in federal census records on websites such as Ancestry.com or FamilySearch.org, or on microfilm.

Original schedules for 1820 are on NARA microfilm series M279. Some schedules for 1850 to 1880 are on Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online. These may be in the same databases as the agricultural schedules noted above. The 1885 census records for all areas except Dakota Territory are on microfilm at NARA.

5. Slave Schedules

In 1850 and 1860, Southern states and Washington, D.C., submitted schedules of slaves; New Jersey did in 1850 as well. These schedules list slaveholders and information about each enslaved person. Though slaves aren’t named, they may be able to help you identify a family’s slaveholder.

Record content

Slaveholders are listed in the same order as on the population schedule. While population schedules don’t indicate who owns slaves, the 1860 census lists a person’s personal property value, which included slaves. A white person with a relatively high personal property value in 1860 may appear as a slaveholder in the slave schedule. The slave schedule may indicate whether multiple slaveholders or a trust was involved in “ownership.”

Unfortunately, nearly all the enslaved are described only by age, gender and color (black or “mulatto”) under the slaveholder’s name. Only rarely will you find more data about the enslaved, such as a name, occupation or physical or mental disability. Without additional research, it’s usually impossible to know whether a slave listed is really your ancestor.

Tip: Look for every family member in every available special census. Most local lists are quite short and are easy to browse.

Under each slaveholder’s name also appears a tally for the preceding year of manumitted (freed) slaves and fugitive slaves not yet recaptured. Again, you won’t know for sure if these figures include your enslaved ancestor without more research.

Access

Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online have the slave schedules. See the the 1850 and 1860 slave schedule databases at Ancestry.com. FamilySearch.org has the 1850 slave schedule. Microfilmed slave schedules are at NARA. The FHL has books with slave schedules and/or indexes from various states. Check the FamilySearch catalog or search the digital books collection.

6. Veterans Schedules

Some censuses identified members of the military, from the 1840s column for Revolutionary War pensioners to two columns in 1930 for veterans of wars and military expeditions. But in 1890, an entirely separate veterans schedule was created. The surviving portion makes a neat substitute for the lost 1890 population schedules.

Record content

Population schedules in 1890 identified Civil War veterans and their widows. Enumerators then transcribed their names onto veterans schedules. Only Union soldiers were supposed to be transcribed, but some Confederate veterans’ names were included. They were later crossed out, but may still be legible.

Pension records, unit rosters and other military records also were used to compile the 1890 veterans schedules. The government sent follow up correspondence to veterans and took out newspaper ads requesting data, making the final veterans schedule even more complete. For each individual, you may find name, rank, company, regiment or vessel, enlistment and discharge dates, length of service, post office address, and a brief notation of any disability incurred.

Other veterans schedules of note

Revolutionary War pensioners: Names and ages of these pensioners were recorded on the backs of 1840 population census sheets. Their names are in A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services, available free through Google Books.

Special military schedules: During the 1900, 1910 and 1920 federal population censuses, enumerators created separate schedules for military personnel, including those stationed on naval vessels and at US bases overseas. For 1900, these are on National Archives microfilm T623, rolls 1,838 to 1,842 (find a Soundex index on film T1081, rolls 1 to 32). For 1910, military and naval enumerations are on film T624, roll 1,784; there’s no Soundex. The 1920 schedules for overseas military and naval forces are on film T625, rolls 2,040 to 2,041; the Soundex is on film M1600, rolls 1 to 18.

The 1930 population census included servicemen, but you’ll find special schedules for merchant seamen serving on vessels. Search them on Ancestry.com, or browse them on microfilm at the FHL and National Archives.

Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Access

The 1890 veterans schedule survives for states alphabetically from Louisiana through Wyoming, plus half of Kentucky, Oklahoma and Indian territories, and Washington, D.C. Search the schedules on Ancestry.com, HeritageQuest Online and FamilySearch.org. Libraries also may have the schedules on microfilm.

How to Read the 1890 Veterans Schedule

- The home and family number refers to the 1890 population schedule, which mostly doesn’t exist. The number still may be useful: Line 18 lists veteran Henry L. Pilchard. The next line is likely his wife, as she has the same home and family number, and surname. She’s listed as the former widow of another soldier, so she remarried to Henry Pilchard.

- This census was taken 25 years after the Civil War ended. Rank, company, regiment or vessel, dates of enlistment and discharge and length of service may be imprecise or missing.

- The line number from the top half of the page is repeated here, with the person’s post office address, service-related disabilities and additional remarks.

You’ll find the 1840 Revolutionary War pensioners census on Ancestry.com.

7. Defective, Dependent and Delinquent Schedules

As part of the 1880 census, the federal government counted ailing, institutionalized and welfare-receiving US residents in the population census. If you see an ancestor with a positive answer in these columns (columns 15-20) and/or who was in a prison, poorhouse or other facility, search for him or her in a separate schedule of “defective, dependent and delinquent” classes (often called DDD schedules).

Record content

This schedule was meant to help the nation assess the needs of its most vulnerable. Census-takers collected data on seven separate forms. In addition to names, places of usual residence and (if applicable) institutionalization, each schedule contained the following information:

- Schedule 2 for the “insane”: whether someone was or had been institutionalized, the nature and duration of the illness, whether restraints were needed and whether the person was epileptic, suicidal or homicidal

- Schedules 3, 4 and 5 for “idiots” (those with severe mental deficiency since childhood), “deaf-mutes” and the blind: comparable data to the above, plus causes of these conditions

- Schedule 6 for homeless children in institutions: whether parents were deceased, guardianship status of living parents, legitimacy of the child’s birth, “respectability” of the child’s background, the child’s criminal history, and whether blind, “deaf-mute” or an “idiot”

- Schedule 7 for the incarcerated: status of a person’s term (such as awaiting a trial or serving out a fine), reason and length of stay, and the nature of any hard labor

- Schedule 7a for the poor receiving public aid: who was paying for the person’s care; details about health, disability, sobriety and criminal background; and which (if any) family members were with the person in the institution

Because families weren’t trusted to report all qualifying relatives, enumerators were supposed to ask around town about who fit the bill for DDD data. Overseers and wardens were consulted on behalf of the institutionalized.

Access

More than 325,000 DDD records for 21 of the then-38 states are on Ancestry.com. Some of these schedules may be in a state archive or library, with many microfilmed copies at NARA.

8. Social Statistics Schedules

Community organizations and resources were described in the social statistics schedules of the 1850, 1860 and 1870 censuses. While they don’t name individuals, you may find them useful for discovering details about your ancestors’ towns.

Record content

You’ll find details about churches, cemeteries, social clubs, schools, newspapers and more. Use these lists to look for records that may name your kin.

Access

Most of these schedules survive. They’re available at NARA and sometimes at regional and state archives. Many are available for browsing on Ancestry.com. Under Browse This Collection, choose the State and Schedule Type, Social Statistics, (if available).

9. State and local censuses

Just as the federal government counted the US population every 10 years, a number of states took regular or semi-regular enumerations. New York, for example, took state censuses in 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1875, 1892, 1905, 1915 and 1925; all are open to the public. Other states held “one-off” censuses, such as the Kansas State Board of Agriculture’s 1885 count.

Five states or territories took an 1885 census, which, if you’re so lucky as to have ancestors there, can help you replace the missing 1890 federal census. Colorado, Dakota Territory, Florida, Nebraska and New Mexico Territory took advantage of the federal government’s offer to subsidize a census that year. Four schedules make up this census: population, mortality, agricultural and manufacturing. Ancestry.com has 1885 census records for some areas. Also try running a Google search on the state or county and “1885 census” to turn up free online resources such as the Larimer County, Colo., 1885 index.

Information recorded varies with the state and time period. In some state censuses, you’ll find details about immigration, citizenship and ethnicity—important for descendants of immigrant “birds of passage,” who may be missing from federal censuses due to repeated travel between the United States and their homelands.

A few states took military censuses, such as the Dakotas’ 1885 Civil War veterans census (on NARA microfilm GR27, roll 5). An index is also available at the South Dakota State Historical Society. To see if your ancestral state did so, run a place search of the FHL catalog and look under both the census and military topic headings.

Check with the state archives or run a Google search on the state name and census records for information about ancestral state censuses. For a state-by-state listing of these schedules and their availability, see Ann S. Lainhart’s State Census Records (Genealogical Publishing Co.). Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org have some state censuses; also look for them on microfilm at the FHL and local libraries.

Written by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Special Census Schedules By Year

Consult this list to see which special censuses might cover your ancestors:

General

- Defective, dependent and delinquent schedules: 1880

- Agricultural censuses: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880

- Manufacturing and industry schedules: 1820, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880

- Slave schedules: 1850, 1860

- Mortality schedules: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1885 (some areas), 1900 (Minnesota only)

- US state/territorial census: 1885 (some areas)

- Social statistics schedules: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1885

American Indians

- Indian schedules: 1880, 1900, 1910

- Indian reservation censuses: 1885 to 1940

- Indian school censuses: 1910 to 1939

Military

- Revolutionary War pensioners: 1840

- Civil War veterans schedule: 1890 (half of Kentucky and states following alphabetically)

- Schedules of military personnel on bases and vessels (including overseas): 1900, 1910, 1920

- Schedules of merchant seamen on vessels: 1930

Written by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Other Special US Census “Fast Facts”

Jurisdiction Where Kept: primarily at National Archives, with a few at state, regional, private or university archives

Online Search Terms: [name of schedule] + US census + year + place

Find in the FamilySearch Catalog: Search by Place, and then select a Census option from the list of results to see whether a non-population schedule exists for that place and year

Alternate and substitute records: varies depending on type of schedule

A version of this article appeared in the December 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT