Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

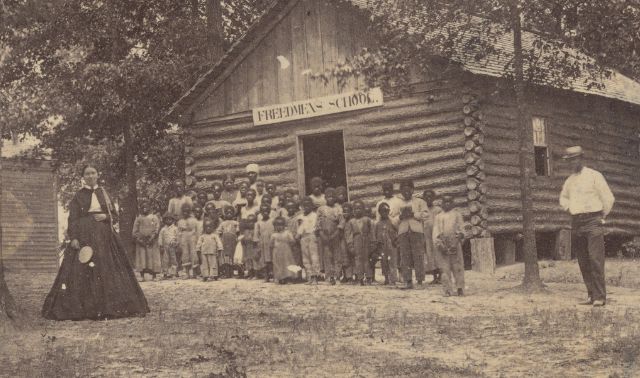

The enslavement of many African Americans before the Civil War shut this group from legal personhood and the records this status entails. That includes newspaper mentions we’re accustomed to finding on white ancestors: real estate transactions, probate notices, death announcements, and others.

But mainstream newspapers didn’t entirely ignore those who were enslaved—especially when they tried to get away. And after the war, African American-owned papers would run touching pleas from freedmen seeking family members who’d been sold away from them. Recognizing the historical significance of slavery, papers also sought to preserve and share memories of those who’d been enslaved. It’s getting easier for you to locate these news items, thanks to the digitization of historical newspapers and projects to create free databases of newspaper items that name these rarely recorded people. We’ll show you what you could discover about your African American family tree and offer tips to help you find it.

1. Fugitive slave ads

The first widespread mentions of African-Americans by name in newspapers were the pre-Civil War fugitive slave or “runaway” advertisements. Slaveholders would place these, often offering rewards for the return of what they considered to be valuable property. Historians estimate that upwards of 100,000 of these advertisements appeared in newspapers from the Colonial period through the end of the Civil War. See an example on the next page. You’ll also find similarly descriptive notices seeking slaveowners of captured African-Americans.

To help readers recognize the escaped slave, ads would offer loads of details about the individual: name (first only, as enslaved people didn’t have legally recognized surnames), age, height, build, complexion (“bright” indicating a person of lighter skin) and markings (often the result of severe punishment). Further detail might include personal and family history details, such as when and where the person was bought or sold. Some ads venture a guess about where the enslaved person might be headed and why. You’ll also see the slaveholder’s name, which can help you follow your enslaved ancestor back in time (learn about this process). This level of information contrasts with the anonymity of enslaved individuals in other records: US censuses, for example, merely count the enslaved.

You can find many of these ads in digitized newspapers using keyword searches, such as fugitive, ran away or absconded, plus the name of a person (the slave or the slaveowner) or place. You also can narrow the time period to 1865 and earlier. Ads might appear in states beyond the location of the runaway’s home, so don’t narrow the geographic scope too much. Try newspaper databases such as GenealogyBank, Newspapers.com and the free Chronicling America.

Freedom on the Move: A Database of Fugitives From North American Slavery will make it easier to locate runaway notices. Cornell University associate professor of history Edward E. Baptist is leading the ambitious project to compile, digitize and index fugitive slave ads in North American newspapers.

Crowdsourcing efforts to build the database include class assignments in which professors and students analyze ads, as well as providing individuals and historical or genealogical societies with opportunities to participate. The process involves correcting errors introduced by optical character recognition technology in “reading” the ads. The project, which received a National Endowment for the Humanities grant in August, could lead to better knowledge of the routes African-Americans used in their attempts at self-liberation. The narratives drawn in the ads may serve to emphasize the individual nature of each slave’s escape. Not all—perhaps even a minority—adhere to the dominant narrative of escape along the Underground Railroad.

2. Reflections on enslavement by former slaves

Even before the Civil War, some abolitionist newspapers ran autobiographies of formerly enslaved people. These narratives became more popular after the war, mostly in the black-owned press but sometimes in mainstream newspapers, too. They related the personal reflections of people who had persevered through the slavery era.

Joe Clovese, at 105 the last surviving African American member of the Grand Army of the Republic, recounted his 20-plus-year search for his mother to the Indianapolis Times and Indianapolis News in 1949. A chance conversation with another patron of the French Market in New Orleans had led him to his mother’s home only a few blocks away.

Articles like those about Joe have been overshadowed somewhat by the narratives and oral histories produced by the Depression-era WPA Writers Project. Many of these newspaper autobiographies and narratives, though, were published closer to the time of enslavement and therefore might be less subject to faded memories. Search for these articles in the aforementioned newspapers websites with the person’s name.

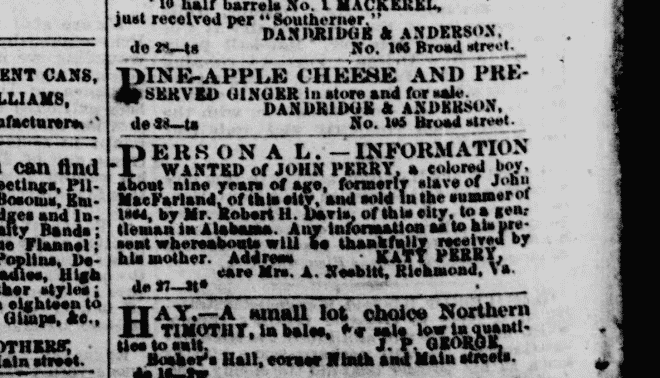

3. Information wanted notices

But as compelling as antebellum ads for runaways and postbellum reflections on slavery are, they pale before the heartache of a third type of distinctly African-American newspaper item: notices from people who sought family members torn from them during slavery.

From the moment they were snatched from their homeland to the auction block, separation was a reality that confronted millions of enslaved Africans throughout their lives. Even attempts to escape North or into the lines of advancing Union armies continued the cycle of separation. War didn’t help their situation: Perceptive slaveowners sold their chattel in advance of the freedom they saw on the horizon. Others removed African-Americans to distant locations they deemed safer. Postwar chaos displaced people all over the South. This experience is detailed in Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery by Heather Andrea Williams (University of North Carolina Press).

The peace at Appomattox set the majority of newly freed African Americans into motion with the objective of finding their families. Although not tasked with reunifying families, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands (better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) nonetheless received scores of requests for help. Surviving bureau records include correspondence and transportation vouchers for those in search of parents, spouses and children. But the agency also slowed the reunification process by transporting freedmen away from their communities to labor opportunities both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

4. Family search notices in African American newspapers

It’s somewhat serendipitous that the African American press is the instrument though which many former slaves found family. Generations of enslaved people were denied the opportunity to learn how to read and write. Defying this prohibition could lead to brutal consequences. The freedmen’s pent-up desire for knowledge manifested itself in the formation of newspapers. The Black Republican, Colored Tennessean and South Carolina Leader came into existence the year that hostilities ended, 1865. The New Orleans Louisianan began semi-weekly publication in 1866 and the illustrated Indianapolis Freeman started in 1888.

According to the 1913 edition of the Negro Yearbook, 288 newspapers served a primarily black audience. Over the whole of American history, the Library of Congress’ US Newspaper Directory shows more than 2,000 entries for African American papers. Read more about these papers in The Negro Press in the United States by Frederick G. Detweiler.

The Christian Recorder was the official newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. It gained fame during the Civil War for publishing the letters of soldiers who were serving with the US Colored Troops. Postwar, the paper published inquiries from these soldiers and others who were looking for families. Notices were generally shorter than 100 words, and typically named both the relatives and a slaveowner. This example appears on page 4 of the Aug. 3, 1899 edition:

Information wanted of Moses Marlow or Howard, who belonged to John Howard in Leflore county, near Smith Mill, and about nine miles from Greenwood, Miss. His mother was Ersia Howard. His father was Matthew Howard. His mother had three sisters: Jane Pierson, Silva House, Clarenda Miller, and two brothers: Louis Moore and Robert Moore. Mrs. Clarenda Miller is the mother of the writer, Ersia Jurault, of Whaley, Miss. Ministers at Vicksburg please read to congregations.

Notices also often specify locations, and might even state when and to whom slaves were sold. Judith Giesberg, professor and director of the graduate program in history at Villanova University, is working with Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia to digitize and transcribe the Christian Recorder advertisements. The site, Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery, has more than 1,500 entries so far and now includes other newspapers, too. You can browse by newspaper or search transcribed information using the search box on the left. Look on digitized newspapers websites, too, searching for names and other terms associated with your relatives. Try including the phrase “information wanted,” which appears in many of these ads.

Most newspapers charged for the ads, but the Herald of Kansas, published in Topeka, is an exception. Its Information Wanted section states “Notices under this heading, not exceeding ten lines, will be published free of charge.”

No one knows how many such advertisements resulted in reunions. In the 1890s, when the Indianapolis Freeman printed ads in a column titled “A Searcher Locaters Place USA: Lost Relatives,” it stated that, “The Freeman goes to all parts of the world and has been the means of bringing hundreds of Lost Relatives and friends together.” A search of the newspaper turns up only a few success stories reported on. The Last Seen website and other sources also reveal a scattering of triumphs.

Writer Dionne Ford’s great-great-grandmother Tempy Burton placed an ad in the June 4, 1891, Southwestern Christian Advocate. She sought her mother, siblings and aunts. Just over a month later, Tempy again wrote the paper, joyfully reporting that she’d found her sister. Ford shares the story on her blog.

The ads were also a common way to search for relatives who became separated after the war. Ellen Tate, a wife, mother and AME church member, placed a notice in the Information Wanted column of the March 26, 1887, Cleveland Gazette. She sought her 28-year-old son:

Any information of the whereabouts of Fred Tate, who left his home in Zanesville, O., May, 1884, will be thankfully received by his mother, Mrs. Ellen Tate, No. 109 Muskingum avenue, Zanesville, Ohio.

You’ll find that African American newspapers often had a larger geographic reach than mainstream papers. Publishers were keenly aware that much of their audience had kin in other areas, and therefore focused more of their “out-of-town” news on the places from which their closer geographic base had migrated. As with most genealogical research, the newspaper notices we’ve described can be helpful even if they don’t name your ancestors. An ad for a runaway from the same plantation as your ancestor, for example, might give clues about your relative’s conditions of enslavement. A distant relative’s reunion ad might mention other family you weren’t aware of.

After centuries of separation and dislocation, the increase in digitized newspapers and emerging databases of advertisements are expanding the access and reducing the difficulties in finding these distinctive references to African-Americans. It’s all resulting in new ways for researchers to discover family and overcome the genealogical barriers of slavery.

From the January/February 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT