Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

1. Catch ‘Em If You Can

According to family information, my great grand father Martin Doran left Minneapolis in 1917 or 1918, and the family never heard from him again. Where do I begin looking for him?

To plan and evaluate your research on any elusive ancestor, first create a documented chronology showing everything you know about him and his family, including the date and location of each event. Update the timeline as you learn more.

Then work back in time to identify his spouse, children, siblings, parents and even grandparents, especially in family records and censuses of 1910 and before. Then work forward again, studying all the relatives you can find and watching carefully for clues about Martin. Try relatives’ obituaries: Sometimes people who had little contact with their families returned home for funerals and were mentioned in obituaries.

Look for Martin’s relatives, as well as Martin himself, in the 1920 and 1930 censuses, using the subscription-based Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com >, or Ancestry Library Edition or HeritageQuest Online <www.heritagequestonline.com> (available at subscribing libraries). Consider that a Martin Doran listed in the census may be your ancestor, even if details such as birthplace and age don’t match the facts you have. Also, search census and other records on his middle name (instead of his first) as well as alternate spellings of his surname.

Next, survey broad record groups. City directories can help you identify Martin Dorans in various cities. If your Martin left home about 1917 or 1918, perhaps he served in World War I or registered for the draft. If he attended college, check into alumni records. Search the Social Security Death Index at Ancestry.com, FamilySearch <www.familysearch.org> or RootsWeb <www.rootsweb.com>, and consult online state death indexes. Then research some of the Martins you find to determine if he’s your ancestor.

Online surname databases and message boards, such as GenForum’s <genforum.com/doran>, also may provide more clues—but carefully evaluate and document anything you find in these sources.

— Emily Anne Croom

2. Here, There, Everywhere

A recurring question keeps imposing itself into my family history research: How did they get from there to here? More specifically, what routes and what modes of transportation did my ancestors use to get from Pennsylvania to North Carolina in the mid-1700s and from North Carolina to Missouri in the mid-1800s?

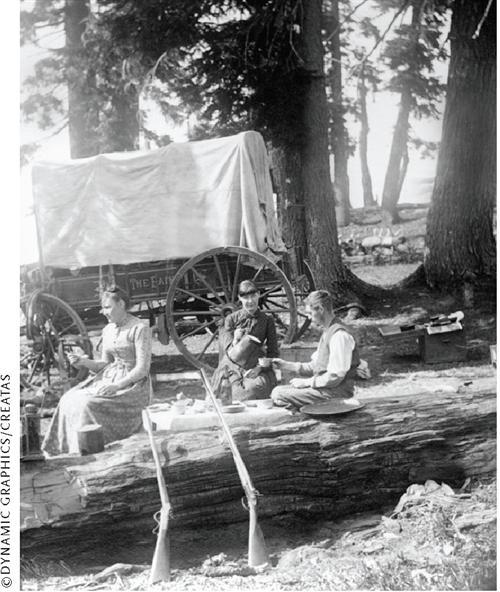

Depending where in Pennsylvania the travelers began their journeys and where in North Carolina they ended up, you may be able to narrow the choices for their migration routes. Travelers from Pennsylvania to North Carolina in the mid-to-late 1700s usually followed traditional Indian paths that gradually had been widened to accommodate teams of oxen or horses pulling wagons. Many people walked or rode horseback along the wagon roads. Travelers could begin on the Great Valley Road (also called the Great Wagon Road) at Hagerstown, Md., and go southwest through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, then turn south at present-day Roanoke, Va., and continue into central and western North Carolina. Others followed several roads from Richmond and Fredericksburg, Va., south into eastern North Carolina. A few may have gone by ship to Norfolk, Va., or Charleston, SC, and continued their trek overland into North Carolina, as this state had few harbors sufficient for large ships.

Ancestors going from North Carolina to Missouri in the mid-1800s could have traveled the Tennessee River to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and ended up at a number of destinations in Missouri. Others went overland by such routes as the Jonesboro Road from North Carolina to Knoxville and Nashville, Tenn. From there, they chose various roads to Missouri. By the 1850s, a number of relatively short railroads crisscrossed the landscape between North Carolina and Missouri, more running north and south than east and west.

Numerous historical atlases and histories of the westward movement in America depict the overland routes. Our ancestors frequently traveled with relatives or fellow church members; thus, histories of ethnic or religious groups sometimes describe their migration routes. Histories and eyewitness accounts of travel in the ancestral time period often shed light on the details of such journeys. Search online library catalogs to identify specific titles.

— Emily Anne Croom

3. Alien Encounters

How do I find information about my ancestors who never became naturalized citizens? My grandparents were required to register annually as aliens. The registration forms were available at our local post office. Have these records been stored anywhere and can I get copies?

Aliens were required to register their current addresses and places of employment with the federal government between 1940 and about 1982. The Alien Registration Act of 1940 required aliens to supply this information and immediately report any change of address. Beginning in 1952, aliens had to report their addresses annually. The address reporting ended in the 1980s, and only the last or most recent address might remain on file. For more background on alien registrations, read the US Citizenship and Immigration Services’ (USCIS) article “Why Isn’t the Green Card Green?” at <uscis.gov/graphics/aboutus/history/articles/green.htm>.

A small staff at the USCIS Historical Reference Library will respond to limited requests about specific documents. Direct questions about the library’s holdings to the librarian at Ullico Building, 111 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20529, or cishistory.library@dhs.gov. For more information about the USCIS Historical Reference Library, visit <uscis.gov/graphics/aboutus/history/library.htm>.

— Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

4. Covert Operation

I’m looking for service records of Phoebe Lou Parsons, a Red Cross US Army nurse during World War I who served in base hospitals. Where can I find these records? I’ve tried looking for records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) with no luck.

Many records relating to individuals’ war service from World War I are at NARA’s National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, Mo. <archives.gov/st-louis/military-personnel/public/archival-programs.html>. A 1973 fire destroyed many records, and most 20th-century military records of use to genealogists aren’t as abundant as records from earlier wars.

Your inquiry didn’t mention which NARA facility you checked or with whom you spoke, but NARA <archives.gov> does have many records concerning WWI , nurses. It will be important for you to determine if the person was actually in the Army or was a Red Cross nurse. You also need to know at what hospital(s) she served. NARA stores some records of military individuals in the hospital records, but they’re organized by hospital and aren’t indexed by individual names. Additionally, you might want to read the helpful tutorial American Women and the US Armed Forces: A Guide to the Records of Military Agencies in the National Archives Relating to American Women (NARA). Visit <archives.gov/publications/finding-aids/guides.html#amwomen> for more about this guide. Once you find some records of interest, you should contact NARA to determine where they’re actually housed.

Many states also have records related to those who served in the military during World War I; check the state archives. Look for published histories about WWI nurses and women in the military, too.

— Paula Stuart-Warren

5. Call the Doctor

My great-great-grandfather was supposedly a physician in the mid-1800s. He left Pennsylvania for Ohio, and died in 1870. How can I research where he got his education and verify that he was a physician?

Start with the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Deceased Physician File, 1864-1970. In these records, you may find an obituary and other biographical information, such as specialties and medical schools your ancestor attended. The file is available on microfilm at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> in Salt Lake City. To find the film, go to the Web site and click the Library tab, then Family History Library Catalog. You can borrow microfilm for viewing at your local FHL branch Family History Center (FHC). In the Author search, type American Medical Association. Results show the physicians’ names in alphabetical order; they’ll include some Canadian doctors, as well.

The National Genealogical Society (NGS) also has the AMA file. Go to <www.ngsgenealogy.org/library/deceasedphysicians.cfm> and click on AMA Deceased Physician Research to make a request.

To research doctors who practiced before 1864, look for the two-volume Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929 (American Medical Association, out of print); you’ll find it at many libraries and on CD at the FHL. You also can search the directory online at the subscription-based Web site Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com/507facd.html>.

If you don’t find your ancestor in the AMA files, check city directories from his towns to see which medical schools were in operation. The College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania), which opened in 1765, was the first medical school in the United States. Ohio had a number of schools, including the Medical College of Ohio. It was founded in Cincinnati in 1819 and later merged with the University of Cincinnati. (A different Medical College of Ohio was established in 1964 in Toledo.) Check online to see if the colleges still exist or have changed names. If the schools are still around, write to their registrars to inquire about your ancestor’s records.

—Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

6. Mother-Son Bonding

My ancestor Patience Breeden was an indentured servant of John Oldham in Virginia. She gave birth to a son, Bryan, about 1701. Court records state that Patience would be indentured an additional year, and Oldham would keep Bryan until he was 21. I suspect that Oldham was Bryan’s father. How can I prove this, and learn what happened to Patience?

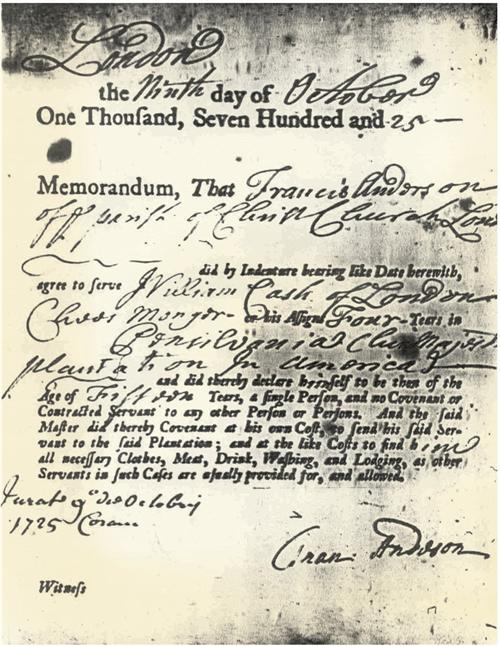

An indentured servant entered into a contract for a specific number of years, in exchange for his or her passage to America. Indenture documents generally give the names of the servant, her parents and her master; the location and length of indenture; and sometimes immigration information.

Records of indenture can be hard to locate because they’re held in a variety of places: Some, such as the ones you found, are part of court records; others are in collections of the master’s personal papers. Patience’s court records mention her child because her pregnancy extended her term of indenture. Establishing paternity may be difficult or impossible unless you can find a document, such as an additional indenture contract for Bryan, in which Oldham claims to be his father. Since Patience gave birth out of wedlock, you could look for a bastardy or fornication case against her.

I would start by checking local and state archives, such as the Library of Virginia <www.lva.lib.va.us>, for John Oldham’s papers, then searching court records in hope that the documentation exists. It may not, though, so be prepared for disappointment. Also try Virtual Jamestown’s online database <www.virtualjamestown.org/indentures/search_indentures.html> of more than 10,000 late 17th-and early 18th-century indenture contracts from English registers in London, Middlesex and Bristol.

— Maureen A. Taylor

7. The XYZ of DNA

I was adopted and I’m trying to prove my surname connection to a possible biological relative. I believe I’ve found a male third cousin. Each of us is in a direct male line back to a common great-grandfather. Which Y-chromosome test(s) would be appropriate to prove the relationship?

Your situation is an ideal application of Y-DNA testing, especially since you’ve already developed a theory to test. Y-chromosome tests come in a variety of “resolutions.” Just as higher-resolution printers provide a clearer picture than low-resolution ones, higher-resolution tests provide greater accuracy. Resolution is measured in “markers,” or locations on the Y-chromosome. The more markers the test evaluates, the higher its resolution.

In your situation, a basic 10- to 15-marker test would probably be sufficient to determine whether you’re related to your suspected cousin. That’s because you’re simply looking for a haplotype match, rather than trying to estimate the number of generations back to a common ancestor. (Haplotype is the term for a set of Y-DNA test results.) But I’d suggest that you opt for a mid-range test of 23 to 25 markers. This will reduce the possibility of a false-positive match. Although it’s extremely rare for two unrelated men to match closely on even a low-resolution test, it can happen if your haplotype should prove to be a very common one. (Like surnames, some haplotypes are more common than others.) Given the personal importance of this test, I’d take the extra precaution. To learn more about what genetic genealogy can do for your research, see the February 2005 Family Tree Magazine.

— Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak

8. Seeking Slovaks

I’ve read that Catholic Church records in Slovakia were destroyed during World War II. How can I find baptismal records for my father and his siblings?

Actually, most Slovak Catholic records are intact. You have especially good odds of finding baptisms for people born before the mid-1890s. But first, it’s important to know which kind of Catholic—Roman or Greek—your family was, as present-day Slovakia is home to people of both religions. Signs your family might have been Greek Catholic include attendance at Byzantine or Carpatho—Russian (also referred to as Carpatho—Rusyn) Orthodox churches, and documents (such as passenger-arrival records) listing Ruthenian as the nationality.

Some Catholic parish registers of both varieties date back as far as the mid 1600s while others don’t start until the late 1700s. In the 1950s, the Czechoslovakian government declared all church registers state property and began gathering ones created before 1895 into regional archives under the Ministry of the Interior. With some exceptions, more-recent registers are at local village offices and churches. In fact, to meet official requirements, many churches have copied their records annually and retained a second set.

The best source for pre-1900 records is the FHL. Go to the FamilySearch home page and click the Library tab, then Family History Library Catalog. Select Place Search and enter your ancestral town’s name. A search for Plavec, for example, brings up microfilms containing Roman Catholic Church records for 1743 to 1896. You can order any promising films to view at your local FHC for a small fee.

If you can’t find the records you want, try searching on neighboring villages (not all towns had their own churches) and check the catalog again every few months for new releases. You also could write to the church or the mayor (have your letters translated and include a small donation), hire a local researcher or contact the Slovak Ministry of Interior. Go to <www.centroconsult.sk/genealogy/resources. html> for contact information as well as additional details.

— Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak

9. Family Secrets

I’ve run into a new kind of brick wall-my great-grandmother’s diary is partially written in code. A normal-sounding entry is followed by something like “May 20, 1904=l^-X#l ll=D 0,:” Do you have any ideas how I might decode this entry?

Women were known for coding their diaries because some things were too intimate to write about, even in a diary. Without analyzing the full diary and the exact code, it’s impossible to speculate on what your great-grandmother was coding. But you can look for patterns to help you crack the code.

Women most commonly coded their diaries to keep track of their menstrual cycles, and the codes are as unique as the woman. One diarist used three exclamation points, another merely a p. In Seasons for Growing: The Diaries of Lizzie A. Dravenstatt, 1870-1928, edited by Patricia Sanford Brown (PS Brown, out of print), Lizzie marked a date almost monthly with an asterisk.

Even famous women, such as children’s author Beatrix Potter, coded their diaries. The editor of Potter’s diary explains how he broke the code in the introduction to her journal: See The Journal of Beatrix Potter, from 1881 to 1897 (Fredrick Warne & Co., out of print), for a transcription of her coded writings.

Another common code in diaries of men and women is the use of only initials for people the diarist wrote about. Nothing is more frustrating than to find an entry recording a marriage proposal from “K.T.,” whom the diarist rejected, with nothing further to identify the suitor. If your ancestor lived in a small community, however, you may be able to figure out who the person in question was through research in other records —that is, assuming the diarist used more than one initial. Common also was “J- came to visit today.” This wasn’t necessarily an attempt to be secretive. Why should your ancestor write out the whole name? She knew whom she was talking about.

—Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

10. Tracking Orphans

How can you trace children before their adoption? In early August 1859, David Supple traveled to Noblesville, Ind., on an orphan train. I haven’t been able to get his birth certificate. I know his parents’ names and that he was born Sept. 22, 1848, in New York. He was an orphan when he was brought to the Children’s Aid Society, but I haven’t been able to locate death records for either of his parents.

Obtaining early birth, marriage and death records is a hit-or-miss affair. Although New York began vital registration in 1880, not all areas complied until 1915. Because of this, many births went unrecorded in New York City prior to 1915. The Children’s Aid Society didn’t house children so much as it gathered them up from other orphanages and street corners before sending them on the trains.

Finding the Supple family in the census should be your first course of action. I was able to locate the John and Johanna Supple family in the 1850 federal census. It lists them as living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, 14th Ward. Names and ages given for the family are John, 50; Johanna, 30; Ann, 13; Michael, 9; and David, 4. All were born in Ireland.

Remember that census enumerators sometimes interviewed landlords, neighbors or whoever happened to be handy at the time of the visit. Accuracy can vary greatly, so compare at least two censuses. Try to locate this family on the 1855 state census for New York. If either parent died prior to the census, at least one of the children should be recorded. That child may be listed as an inmate at an orphanage.

Next, post queries on pertinent message boards and write to the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America (Box 322, Concordia, KS 66901; 785-243-4471; <www.orphantrainriders.com>), which maintains records on all known orphan-train riders. If you can determine which orphanage the children were in, your search will be easier.

— Clark Kidder

11. Missing Persons

Can you explain the absence of some family members from federal census reports, when their obituaries indicate that they were residents of the city during that time?

Although census takers occasionally missed people, it’s possible that the obituaries are wrong. Grieving people may forget or confuse the dates when a deceased person lived in a particular place. Look for other sources, such as court records or city directories, to double-check the information.

But let’s assume the obituaries are correct. Why wouldn’t you be able to find your relatives in the census? They may have been counted, but are playing hard-to-get. And locating them may be just a case of learning to play along. For example, the enumerator could have misspelled the surname so badly that you simply don’t recognize it. Have you checked every conceivable spelling of your name? For example, Mitcham might have been recorded as Machun, Mecham, Meekin, Maikin, Machen or even Meachon.

Expand your search to include phonetic spellings, particularly at the beginning of a name. For instance, Ghoggin might have been spelled Goggin. If your name begins with an H, the H may have been dropped and a vowel used in its place, such as Yaeger or Ager for Hager.

The Soundex—an index that groups similar-sounding names—can help you find spelling variations. Microfilmed Soundex indexes exist for 1880 and later censuses; you can search online indexes by Soundex code on HeritageQuest Online <www.heritagequestonline.com> (available through subscribing libraries) and subscription-based Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com >. To get more information on Soundex and calculate the codes for your surnames, see <www.familytreemagazine.com/soundex.html>.

It’s also possible that the census taker got your relative’s first name wrong, or listed his middle name instead of his surname. My grandfather appears on a census as Byron, although his first name was Herschel. If you find someone with the right surname but the wrong first name, don’t discount him—he may be yours. Confirm it in other records.

If you’re sure the family lived in a certain city at the time of the census, try to track down the listings for neighbors or other family members. You never know—your relatives may have been living in another family’s household.

Lastly, don’t confine your search to places where you think your family should be. Expand into nearby areas. County names changed and boundaries migrated, so check records for all possible counties.

An excellent resource guide for locating hard-to-find ancestors in the federal census is The Genealogist’s Companion and Sourcebook, 2nd edition, by Emily Anne Croom (Betterway Books).

— Nancy Hendrickson

12. Little Engineer That Could

My uncle was a B&O Railroad engineer from the 1930s to the ’50s. Family legend has it that he drove one of President Eisenhower’s victory trains. B&O says its records are gone, and the Eisenhower Presidential Library says train engineers weren’t recorded. How can I prove this story?

Some wonderful railroad records do exist, but the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad is one of the sad stories. According to the B&O Railroad Historical Society <www.borhs.org>, many late-1800s and early-1900s records were lost due to various moves and file purging as the company changed ownership.

You may, however, find that items such as payroll records, letters and photographs are still around. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum <www.borail.org> in Baltimore, Md., holds some corporate records, as well as the company’s employee publication, B and O Magazine (renamed Baltimore & Ohio Magazine in 1920). The museum reopened in November 2004, after an 18-month closure for weather-damage repairs. Unfortunately, the library remains closed—check the Web site for updates and additional resources. Use an Internet search engine such as Google <www.google.com> to find the magazine in repositories and on auction Web sites.

The US Railroad Retirement Board, a government agency begun in the 1930s to administer railroad workers’ benefits, also may have records.

Indexes to major newspapers might help you narrow the dates for victory trains your uncle could have driven. Then look for information in newspaper stories, starting with his hometown papers. Read up on the B&O in publications such as Railroad History magazine <www.rrhistorical-2.com/rlhs>, published by the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society. Even if your uncle’s name isn’t mentioned, you may find historical background on the victory trains.

The Eisenhower Presidential Library <eisenhower.archives.gov> staff knows its records, but you might feel better if you check for yourself, so study the library’s online finding aids. Who knows—your uncle’s name could be buried in correspondence about travel arrangements. If you do find a promising collection, be prepared to visit the library and search through records box by box, page by page, without the benefit of an index.

— Paula Stuart-Warren

13. All Not Aboard

My problem is that the US and Irish records I need to find my family were destroyed in fires. I know my great-grandfather died on the ship coming over to the United States. Is there a Web site or other source that lists deaths on ships?

What a wonderful idea! Someone should compile a list of all those who have died aboard ships coming to America. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been done yet, either in print or online. I checked with two Irish experts, two Internet genealogy gurus, The Ships List <www.theshipslist.com> and the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild <immigrantships.net>. None of these people or organizations was aware of any such compilation, either.

Passengers who died aboard ship were usually recorded on the last page of the manifest, or a notation might have been made by the passenger’s entry on the list. Their names should be indexed along with other passengers. Not all ports and time periods have been indexed, however. For more information on using passenger lists and indexes, see my book A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Immigrant and Ethnic Ancestors (Betterway Books, out of print). And read up on places to look for passenger lists online.

I find it unusual that all the US and Irish records you need were destroyed in fires, since many people are successfully doing Irish immigrant research. My suggestion would be to consult two works that will tell you whether the records you need still exist, and if they don’t, other research strategies and records that might indirectly give you the information you seek: A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Irish Ancestors (Betterway Books) by Dwight Radford and Kyle Betit, and Discovering Your Immigrant and Ethnic Ancestors. Consult my book The Family Tree Guide to Finding Your Ellis Island Ancestors (Family Tree Books) if your relatives entered America at that immigration station.

— Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

14. Foreign Flashback

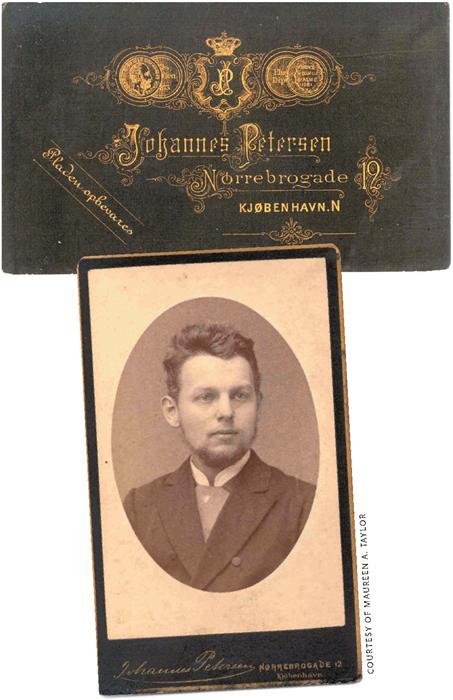

I have a number of pictures of my family taken by foreign photographers. How can I date them?

Dating a photograph by establishing when the photographer was in business is an essential part of photo identification. This research can assign a time frame for the image and ultimately help you identify the people in the picture. You can find the photographer’s imprint in a number of places, depending on the type of image.

Foreign photographs add another wrinkle, of course. When researching foreign photographers, you may need a language dictionary to help you decipher any printing or writing on the image. The town name will also need translating: For instance, Copenhagen can appear as Kjøbenhavn in the imprint. Finding the place in an atlas or gazetteer can uncover the country where the photographer worked. Just keep in mind that many place names changed or disappeared during political upheavals.

You can attempt to research the photographer by using as much of the name as appeared on the image. Two excellent resources can help: The International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House has an online database of photographers at <www.eastmanhouse.org>. Peter Palmquist’s Photographers: A Sourcebook for Historical Research (Carl Mautz Publishing) contains a bibliography of directories of photographers from all over the world.

You also can use city directories and census records if they’re available for the location you’re researching. The WorldGenWeb Project <www.worldgenweb.org> can help you become familiar with the availability of those resources for a particular country. The FHL publishes many country-specific research guides on Family Search; click the Research Guidance link.

If your initial attempts to locate the photographer fail, try using the online genealogy search engines offered by the subscription sites Genealogy.com and Ancestry.com. For example, a search for photographer Johannes Peterson of Copenhagen yielded leads using several of the above search tools.

Researching the photographer is only one of the ways to date a photograph. Costume clues, genealogical research and photographic methods also can help.

— Maureen A. Taylor

15. Friends and Family Plan

My great-great-grandfather is a brick wall I just can’t get past. James W. Crutchfield was born in Orange County, NC, on July 6, 1811. I can’t find his parents or siblings. I can’t find a record of his second marriage to Sallie P. Jones in 1841, although a first marriage to Lavinia Lashley in 1836 is listed. Since censuses only list the head of household before 1850, I can’t go by that. Help!

Consider several questions first. How do you know James W. Crutchfield’s date and place of birth? Where did you get that information? A tombstone? Family Bible? Consider the reliability of the source. How do you know Sallie P. Jones was his second wife and supposed year of their marriage? Have you studied the statewide marriage records for all Crutchfields during the period to look for possible relatives of James? Have you looked for James in all censuses during the time when he could have been a head of household? Have you studied existing 1810, 1820 and 1830 censuses for all Crutchfield households in North Carolina, especially Orange and surrounding counties, for families that may be James’ parents and siblings? If there are Crutchfields in those censuses, have you studied them? Have you studied records of Alamance and Durham counties, which were created out of Orange?

Second, you’ve identified at least three problems you’d like answered: identifying James’ siblings, identifying his parents and finding evidence of his second marriage. You may need to address these separately, one at a time. Although I don’t know what else you know about James and how much research you’ve done on him, I’ll suggest the following ideas:

1. A helpful tool in studying any ancestor is a chronological profile of the person’s life. In the case of James, list in chronological order everything you know about him and note the sources of all that information. Remember to evaluate the reliability of each source. You can solve most “tough” genealogical problems by consulting original records and records contemporary with the events in the ancestor’s life. Use the timeline of what you know about James to help you study him further. You also should list historical events — wars, migrations, county boundary changes—during his life, and the date and place of each.

2. Look for James in these places: records he created (such as land purchases or sales), records created about him (such as widow’s pension or probate records), and records that mention him in other capacities (such as witness, surety or neighbor of someone else). You’ll get ideas about available sources in North Carolina and your specific counties by doing a place search of the FHL catalog for North Carolina. Also consult books such as Alice Eichholz’s Red Book, 3rd edition (Ancestry), and Helen Leary’s North Carolina Research (North Carolina Genealogical Society, out of print). This kind of search may involve not only reading indexes to records but also reading page by page through deeds; probates; and court, tax and other records.

3. Study James’ children as thoroughly as possible in available records.

4. While reading these records, develop a list of people with whom James associated—children, neighbors, friends, people for whom he witnessed documents, those who witnessed his documents, and so on. Many individuals with whom ancestors interacted were their relatives and in-laws. Developing and studying this list of names may help you identify possible family members.

5. Keep an open mind. Look at records in neighboring counties, for instance. As you study the records, be sure to record the source of the information and make note of records you read that don’t give you information. You may or may not find records that say “James W. Crutchfield was the son of …” or “married on XX date.” You may need to piece the answers together like a jigsaw puzzle. That’s often the case in genealogy, but it’s the way we learn about our ancestors and about research. Best wishes for your successful searching.

— Emily Anne Croom

Emergency Workers

Meet the genealogy gurus helping you solve your brick-wall problems:

• Contributing editor Sharon DeBartolo Carmack is a certified genealogist and the author of 15 books, including The Family Tree Guide to Finding Your Ellis Island Ancestors (Family Tree Books).

• Emily Anne Croom is an active genealogy researcher, teacher and lecturer. She’s the author of The Sleuth Book for Genealogists and Unpuzzling Your Past (both from Betterway Books), among others.

• Contributing editor Nancy Hendrickson is the author of Finding Your Roots Online (Betterway Books).

• Clark Kidder is the author of Orphan Trains and Their Precious Cargo: The Life’s Work of Rev. H.D. Clarke (Heritage Books).

• Genetic-genealogy expert Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak is the co-author of Trace Your Roots With DNA: Using Genetic Tests to Explore Your Family Tree (Rodale) and webmaster of Genetealogy <www.genetealogy.com>.

• Paula Stuart-Warren is a certified genealogical records specialist and the co-author of Your Guide to the Family History Library (Betterway Books).

ADVERTISEMENT