Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

As we celebrate the 400th anniversary of Jamestown, Va., let’s pause in recognition of New Mexico’s own venerable city, Santa Fe – which is arguably as old as historic Jamestown. In 1607, around the time those English colonists were unpacking, Juan Martinez de Montoya established the first settlement where Santa Fe is now. Santa Fe wasn’t officially founded until 1610, which still makes it the oldest capital city in the United States.

It’s important to know where in that long and varied history your New Mexico ancestors’ events fall, says Karen Stein Daniel, former editor of the New Mexico Genealogical Society (NMGS) <www.nmgs.org> journal New Mexico Genealogist and author of Genealogical Resources in New Mexico (NMGS Press). That’s because most repositories catalog records by time period. She also warns you may have to scour several locations for the records you need; some county records, for example, are now in the state archives <www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/archives/archives_hm.htm>. Keep in mind that, like other states, New Mexico divided up its counties over the years: For instance, Doña Ana County spun off Grant County, which in turn spawned Luna and Hidalgo counties. See <rootsweb.com/~nmgenweb/table-of-counties.html> to learn county formation dates and names of parent counties. Then you’re ready to dive into the deep well of New Mexico’s past.

Beguiling beginnings

New Mexico’s European history began in 1536, when a small Spanish exploratory party reached the southern part of today’s state and went home telling tales of the golden Seven Cities of Cibola. A search for those reputed riches brought Francisco Vasquez de Coronado around 1540. But the Spanish didn’t come to stay until 1598, when Juan de Oñate traveled up the Rio Grande from present-day El Paso to establish San Juan de 10s Caballeros.

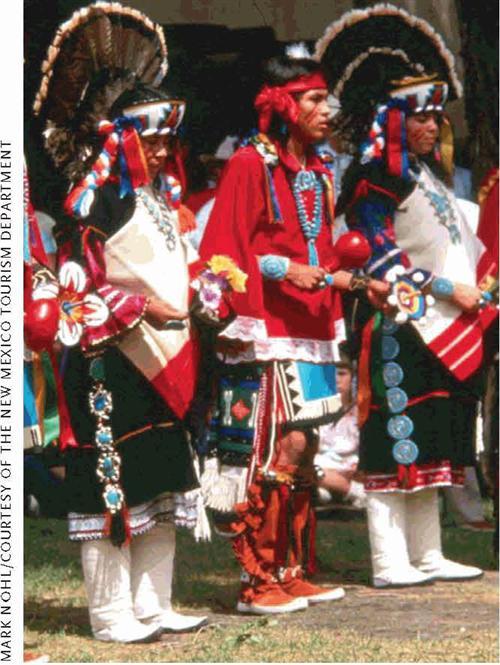

What the Spaniards dubbed Nuevo México already had been long occupied, of course, by native groups. Evidence of the Sandia people’s habitation dates back to 25,000 BC. Other Indian cultures arrived in turn, among them the Mogollon and the Anasazi.

In 1680, the Pueblo — a diverse group of several native cultures-rose up in a revolt that sent the Spanish fleeing. They didn’t return until 1692, under Don Diego de Vargas, who thwarted a second Pueblo revolt in 1696. Next came the Apache, who also proved troublesome to European attempts at taming this rugged country.

If you have American Indian roots, check the Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> for microfilmed Bureau of Indian Affairs records, which document births, deaths, marriages, divorces, land allotments, homesteads and schooling. You can rent microfilm through your local Family History Center; use FamilySearch to find it. The original records, spanning 1878 to 1944, are at the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) Rocky Mountain regional facility in Denver <archives.gov/rocky-mountain>.

The new United States stayed away from New Mexico until 1807, when Zebulon Pike led an American expedition there. Then in 1821, William Becknell blazed the Santa Fe Trail connecting New Mexico with Missouri, an occurrence that coincided with Mexico’s independence from Spain.

For roots in the Spanish and Mexican era, early censuses – including Spanish and Mexican censuses from 1750 to 1830; 1790, 1823 and 1845 Spanish and Mexican colonial censuses; and an 1821 census of Santa Fe and outlying towns – might name your family. Look for them at the New Mexico state archives and in compilations from NMGS. The archives also has Spanish (1693 to 1821) and Mexican (1821 to 1845) land records. For assistance with these, consult Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico and Colorado by John R. and Christine Van Ness (AG Press).

Long before New Mexico’s government began keeping vital records, the Catholic church recorded births, baptisms, marriages and deaths. Records from the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, now at the archives, extend to colonial days; the FHL has microfilmed them back to 1726. (Run a place search of the online catalog on santa fe and look for a church records heading.) See NMGS’ online guide <www.nmgs.org/chrchs-intro.htm> for advice. The society’s published volumes of extracted church records start with baptisms (from 1701) and marriages (from 1726), plus cemetery recordings.

You’ll find the record collections Spanish Archives of New Mexico and Mexican Archives of New Mexico in the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Special Collections Library <cabq.gov/library/specol.html>.

Territorial spell

That first, tentative contact with the United States swiftly changed New Mexico’s destiny – as did the discovery of mining riches, which drew more Yanquis. Legend has it a friendly Apache showed Spanish Lt. Col. Jose Manuel Carrasco the rich copper veins at Santa Rita del Cobre, near today’s Silver City, in 1799. In 1828, the first major gold strike in the West occurred in the Ortiz Mountains south of Santa Fe.

Soldiers from the new nation of Texas invaded in 1841, unsuccessfully attempting to claim the land east of the Rio Grande. After the outbreak of the Mexican-American War in 1846, however, US troops under Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny proved victorious, conquering Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war, awarding most of New Mexico to the United States and fixing the area’s border at the Rio Grande and the Gila and Colorado rivers. The 1854 Gadsden Purchase added southwestern New Mexico and southern Arizona.

The Compromise of 1850 created New Mexico Territory, incorporating today’s state plus southern Nevada and Arizona, which split off in 1863. During the Civil War, Mesilla was briefly the capital of the “Confederate Territory of Arizona.” Confederate Brig. Gen. H.H. Sibley captured Santa Fe and Albuquerque and threatened to conquer the whole Southwest until the Union defeated him at Glorieta Pass.

After the war, the arrivals of the telegraph around 1868 and the railroad in 1878, as well as the 1881 joining of the second transcontinental railroad at Deming, began to tame the rough-and-tumble territory. New Mexico attracted miners and ranchers; some of the latter battled in the turf wars known as the Lincoln County War, which made a legend of Billy the Kid.

Seek pre-statehood New Mexicans in territorial censuses, taken as part of the regular federal head count beginning in 1850. Note the 1860 census covered only the area south of the Gila River. The 1885 state census, which actually was federally administered, listed all household members; it’s available on FHL microfilm. NMGS has published a substitute for the burned 1890 territorial census, 1890 New Mexico Tax Assessments.

The state archives holds a wide variety of records from territorial days, such as land grants, early probates and court papers. Its military records come from the Spanish and Mexican era, the Indian Wars and the Civil War. See <www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/arch~ves/ancestorshtm> for the archives’ genealogy guide. Albuquerque’s Special Collections Library has land grant records, county-level territorial records and territory-era newspapers. (Find titles covering your ancestors’ area at <libdata.unm.edul/nmnp>.) Territorial probate documents are in the records of US judicial district courts at NARA in Denver.

Many of New Mexico’s soldiers rode with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. Find a list in History of New Mexico: Its Resources and People, volume 1 (Pacific States Publishing Co.). NARA and the FHL have microfilmed service records. See the October 2005 Family Tree Magazine for military research advice.

Research magic

Statehood finally came for New Mexico in 1912. It was last in the Union to adopt statewide birth and death records – not until 1920, prompted by war and the flu epidemic. Unfortunately, records access is restricted to immediate family. Church records and obituaries can substitute, and you’ll find a volunteer-created death index (1899 to 1940) at <rootsweb com/~usgenweblnm/nmdl.htm>. For pre-1920 vital records, check with the county clerk in your ancestral county.

From their inceptions, counties usually kept marriage records. New Mexico’s Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) chapter <rootsweb.com/~nmsodar/nmso> published 1880-to-1920 marriage records for Bernalillo, Chavez, Eddy, San Juan, Otero, Quay, Roosevelt and Curry counties (also available on FHL microfilm).

Who wouldn’t want to visit a place called the Land of Enchantment? Before you go, peruse the Online Archive of New Mexico <elrbrary.unm.edu/oanm>, a collection of finding aids for holdings at several primary repositories. Then get ready to be charmed – just keep in mind you’re delving into a history as old as America itself.

ADVERTISEMENT