Bourbon is as closely tied to Kentucky’s heritage as racehorses and bluegrass. It’s America’s only native spirit, recognized by Congress in 1964. Its unusual name probably came from Bourbon County, Ky., where the first distillers crafted their fledgling blends and batches in the late 18th century.

Bourbon is as closely tied to Kentucky’s heritage as racehorses and bluegrass. It’s America’s only native spirit, recognized by Congress in 1964. Its unusual name probably came from Bourbon County, Ky., where the first distillers crafted their fledgling blends and batches in the late 18th century.

Although the original creator of bourbon remains a mystery, those who championed the spirit’s production and helped make it a major industry in Kentucky have not been forgotten. Pioneers who moved into this region in the late 1700s noted the limestone-rich spring water and immediately put it to use in concocting crude batches of bourbon. By the early 19th century, scientists such as Dr. James Crow developed instruments that brought consistency to what had been a hit-or-miss process. Even during Prohibition, two resourceful schoolteachers, Ruth Hanly Booe and Rebecca Gooch, made a profit off bourbon by developing the sugary confections still sold as “Rebecca Ruth Candies.”

Bourbon has come a long way since Kentucky’s early settlers took their first sip. Today the state is a bourbon-producing powerhouse, generating more than 90 percent of all the world’s bourbon. Kentuckians feel an enormous sense of pride and passion toward their spirited product. Regarded as a sophisticated beverage, bourbon is as cherished as cognac in France or Scotch whisky in Scotland. Masters of the trade combine modern techniques with time-honored tradition to create bourbons that can’t be found anywhere else in the world.

You can get a taste — literally — of Kentucky’s more than 200 years of bourbon-making heritage at three distilleries, representing the whole spectrum of the state’s spirits industry, all less than an hour from Lexington.

One of the first things you’ll learn on your free tour is that bourbon production is an industry. As with any industry, the distilleries have stringent regulations by which they must abide when crafting their product. Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey must contain at least 51 percent corn and be produced in the United States. No artificial agents such as coloring or flavoring may be added. Distillation may occur at no greater than 160 proof. Finally, it must be aged for at least two years at no more than 125 proof in virgin white-oak charred barrels.

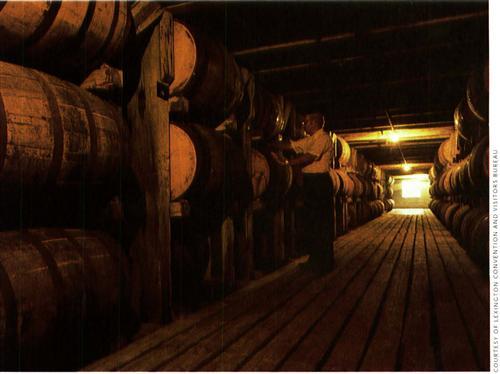

The process for producing bourbon is essentially the same at each of the distilleries, even though they differ dramatically in size and resulting flavors. Corn, rye or wheat and malted barley are added to limestone-rich water and cooked, creating mash. Once the mash has cooled, the distillery’s unique strain of yeast, along with a portion of previously fermented and distilled mash, is added. This yields what’s called sour mash, which ferments for an amount of time unique to each distillery. Once the fermentation period is complete, the solid product is separated from the liquid. This pure substance — commonly known as moonshine — is poured into charred barrels and transferred to on-site warehouses to begin the aging process.

The process may sound time-consuming and tedious. It is. Like fine wines, bourbon increases in value and gets better with age. Each distillery follows identical guidelines and similar processes in crafting Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey. How then does each achieve a bourbon that has its own signature flavor and unique characteristics? The answer lies in the methods of fermentation, distillation and aging you can see up close and personal only on a tour.

BOURBON LEGENDS

Who originally crafted the spirit we now call bourbon? Depending on whom you ask, you’ll get a variety of answers. Here are a couple of the legends that encompass the origins of bourbon, as well as a discovery for a new use of the amber-colored liquor:

• The Rev. Elijah Craig, described as a “cantankerous” Baptist preacher, is said to have mixed the first batch of bourbon in the 1780s in Scott County, Ky. His concoction consisted of rye, barley malt, corn, spring water and various other grains. In addition to his spirited pastime, he founded Georgetown College. The tale goes that he placed a quart of bourbon under all six Ionic columns of the portico of the campus’ oldest building, Ciddings Hall, built in 1839. The Georgetown & Scott County Museum, 229 E. Main St., Georgetown, KY 40324, has exhibits that tell the story of Craig’s life. For more information, call (502) 863-6201 or visit <members.aol.com/scottcomuseum/museum, html>.

• Jacob Spears, recognized for being the first to label his spirit “bourbon whiskey,” resided in Bourbon County, Ky. His home, Stone Castle, still stands, along with the warehouse and spring house on the property. Stone Castle was also one of the first drive-through liquor stores. One of the front windows on the home has a pull-out drawer where change and pint-size bottles of bourbon were kept. Consumers on horseback could pull up and purchase their bourbon at the window. Stone Castle isn’t open to the public, but you can see it by driving on Clay-Kaiser Road in Bourbon County, about an hour east of Lexington. For information on Bourbon County’s attractions, contact the Tourism Commission at (888) 987-3205 or visit <www.parisky.com>.

• Ruth Hanly Booe and Rebecca Gooch, both schoolteachers, found another use for bourbon — candy. The women started a business in an old saloon during Prohibition. They had great success selling their sweet treats. You can buy Rebecca Ruth Candies today and tour the factory at 112 E. Second St. in Frankfort (800) 444-3766 or visit <www.rebeccaruth.com>.

One Moment In Time

As you walk among the cypress fermenting tanks, copper-pot stills, hand-crafted barrels and stone aging warehouses of Labrot & Graham (L&G) in Versailles, Ky., you can’t help but feel you’ve been transported to another era. You can almost picture the Scottish and Irish townspeople gathered to share in the crafting (and consumption) of bourbon in this tiny village. Set against the backdrop of horse farms, this picturesque distillery is where time-honored traditions and techniques for making bourbon are practiced much as they have been for centuries.

Unlike most distilleries, L&G creates only one brand of bourbon — Woodford Reserve. The smallest and the slowest operating distillery in the United States, L&G uses three copper-pot stills made in Scotland to triple-distill its product. “We produce in a year what Jack Daniel’s can make in a day,” says Vicki Lloyd, sales and marketing manager. But there’s a reason for taking the extra time — consistency. To grasp the importance of attaining consistency, you must first understand the history of what L&G boasts is “America’s oldest operating distillery.”

Upon embarking on your tour, you’ll hear the story of Dr. James Crow, a Scotsman, who in 1833 began working at the distillery and who perfected the science of distillation. He championed the use of charred oak barrels, which give bourbon its color and enhance the flavor, and designed special tools for more exact measurements. The original spirit safe he developed is on display and still used to analyze the chemical balance of the spirit. Before Crow’s innovations, bourbon making was a hit-or-miss process, but today his contributions remain industry standards.

In 1878, French wine merchant Leopold Labrot and banker James Graham bought the distillery. With its new name in place, the distillery began gaining momentum but had to close in 1920 because of Prohibition. The future of the distillery hung in the balance. Brown-Forman, one of America’s largest producers of wine and spirits, purchased L&G in 1933 and reopened the plant. But the distillery closed again in the 1960s when demand for bourbon declined. For the next 30 years, the distillery remained abandoned and fell into disrepair. Brown-Forman breathed new life into L&G in 1994 by repurchasing and restoring the distillery.

Today, L&G perseveres in maintaining the integrity and traditions started by the early pioneers of bourbon making. The distillery tightly guards its sacred strain of yeast and rotates its aging barrels to make certain every batch of Woodford Reserve has a consistent flavor, color and superior level of quality.

Labrot & Graham Distillery, located in Versailles, Ky., is about 17 miles west of Lexington, Ky. Tours are given from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday and at 1 p.m., 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. Sunday from April through October. For more information, call (659) 879-1812 or visit <www.Labrot-Graham.com>.

Spirit of the Buffalo

Don’t let the quaint country setting and the gift shop resembling an old-fashioned general store fool you. Buffalo Trace is an enormous operation with the industrial-strength power to produce thousands of gallons of bourbon annually. Located along the shores of the Kentucky River in Frankfort, Ky., Buffalo Trace Distillery offers visitors a unique glimpse of bourbon production on a grand scale.

You may be wondering how the distillery got its unusual name. Centuries ago, herds of buffalo moved west across this stretch of Kentucky, pounding paths or “traces” into the ground. Pioneers followed the buffalo tracks to a clearing along the Kentucky River in the late 1700s. It didn’t take settlers long to recognize that the landscape’s limestone-rich spring water and fertile bottom loam were ideal for bourbon making. Distillation began in the late 18th century on the same site where the bourbon is produced today.

After the repeal of Prohibition, Col. Robert Blanton took control of the business. He introduced his secret-recipe single-barrel bourbon to the distillery. In 1984, the distillery decided to honor Col. Blanton by selling his special-recipe bourbon commercially.

Today, Master Distiller Elmer T Lee continues the tradition of producing quality bourbon. “I think there’s a trend that’s going on right now that started 10 years ago,” Lee says. “One of the things that is growing in our industry is the consumer’s preference for premium small-batch bourbon — single-barrel bourbon.”

While consumers are fleeing from “run-of-the-mill” bourbon, Buffalo Trace has to keep up with demand. With 13 warehouses, 92,000-gallon fermentation tanks, a still four stories tall and 250,000 barrels on site, the distillery is able to produce a lot of whiskey in small batches. But before the public gets a chance to purchase Buffalo Trace Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey, Lee and a panel of tasters must unanimously agree that each barrel meets their standards of quality. Bourbon selection is taken seriously at Buffalo Trace: One strike against a barrel knocks it out of the straight bourbon bottling, relegating it to Buffalo Trace’s secondary product lines.

You can see for yourself how this bourbon-producing giant operates. Regular tours are given year-round Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on the hour. Hard-hat tours (yes, you actually wear a hard hat) last about two hours and are given 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday through Friday from October through March. Call (800) 654-8471 to make an appointment or go online to <www.buffalotrace.com>.

Wild Roots

The story of the origin of the Wild Turkey brand of bourbon is a friendly one, and really does involve turkey. In 1940, an executive named Thomas McCarthy was working for Austin, Nichols, a producer and importer of quality wines and spirits. McCarthy pulled a sample of whiskey from the warehouse of what was then known as Ripy Distillery, and took the whiskey with him to share with his friends on their annual wild turkey hunting excursion. Each year, his friends requested he bring “that wild turkey bourbon” they loved so much. So in 1942, McCarthy began marketing Wild Turkey Bourbon.

The same friendly atmosphere still exists at Wild Turkey Distillery, located in Lawrenceburg, Ky. Master distiller Jimmy Russell has more than 150 employees whose average length of service is 25 years. Jimmy’s son Eddie liked it so much that he signed on to follow in his dad’s footsteps — though he’s a relative newcomer, having worked there a mere 20 years.

Today, the distillery mass-produces bourbon. Twenty warehouses each hold 20,000 barrels. That enormous amount of bourbon then begins aging. Once the aging process is complete, automatic bottling lines clean, fill, label, cork and seal Wild Turkey Bourbon with a speed and efficiency only dreamt of in the past.

But the use of more modern technology doesn’t mean the distillery has turned its back on tradition. In the fermentation rooms, cypress tanks more than 100 years old are still in use. A copper doubler (a large round still where the liquid spirit is sent once it’s separated from the solid product) distills the product a second time. And the highly confidential strain of yeast that’s been passed down from generation to generation is cultivated on site and gives the bourbon its smooth flavor.

Following fermentation, Wild Turkey Bourbon is distilled at a lower proof than most bourbons so less water has to be added before it’s bottled. “Distilling at lower proofs means we get more flavor in our bourbon,” Russell says. The final result is a bourbon with a fuller taste.

Wild Turkey’s flagship brand is Wild Turkey 101. But that’s not the only product you can buy with that popular bird on it. The distillery also makes Wild Turkey 80, Rare Breed, Russell’s Reserve (named for the master distiller), Kentucky Spirit, Rye and Liqueur. When you tour the historic warehouses, Russell has some advice: “If you get the smell of a good, ripe apple, that’s a good bourbon.”

Wild Turkey Distillery offers tours Monday through Friday at 9 a.m., 10:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. Call in advance for groups of more than 10 people. Contact Wild Turkey Distillery at (502) 839-4544 or see <www.wildturkeybourbon.com>.

From the November 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine