Mention the Midwestern part of the United States, and most people immediately think of corn fields, cows, pigs, lakes and flat land. But the Midwestern states also include major cities, leading universities, Fortune 500 companies, scenic valleys, ski slopes, operas, symphonies, museums, five-star hotels, historic sites and, best of all for family historians, a wealth of genealogical resources. The Midwest is home to America’s auto industry and to that staple of genealogical research, the 3M Post-it Note. Here you can find the halls of fame for rock ‘n’ roll, polka, pro foot hall and US hockey.

Exactly what states are we talking about? You could get a different answer to “What’?s the Midwest?” from every person you ask. Here we?re including all the states stretching from the former Northwest Territory until you hit the Plains states of the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas (which many people also think of as the Midwest — I warned you this was confusing!). That is, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Whether you have ancestors in all of these states or just a couple of them, you’ll discover a vast array of resources and libraries for researching your Midwestern roots. Joining genealogical these societies will keep you up-to-date on the ever-growing research projects and resources in these states. As an example, the Iowa Genealogical Society (IGS) works with its chapters around the state to assist them in publishing indexes and abstracts of records. In its Hawkeye Genealogist, IGS has run a series of articles about researching Iowa ancestors.

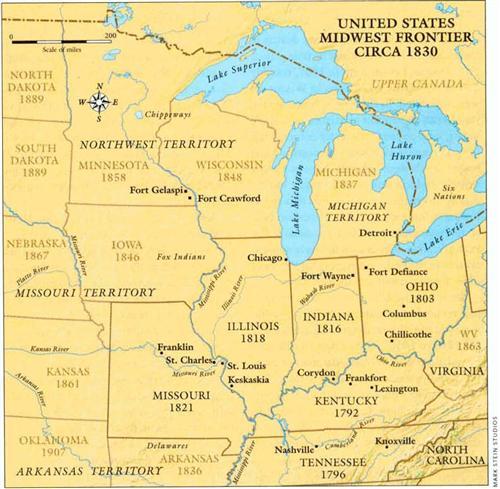

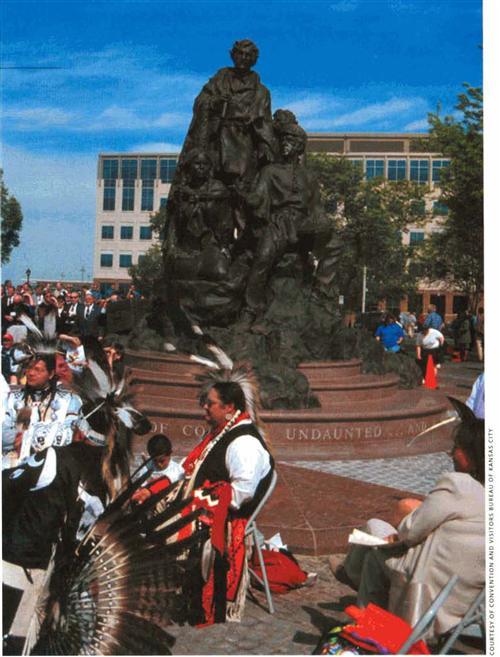

Each of these states was essentially a frontier area at some point in time as the population migrated westward. Each joined the Union in turn between 1803 and 1858. The first people living in these states were American Indians of many different tribes, and their lands and lifestyle were gradually pushed ever farther westward with the influx of new settlers in the 1800s. Some have since returned to their native areas.

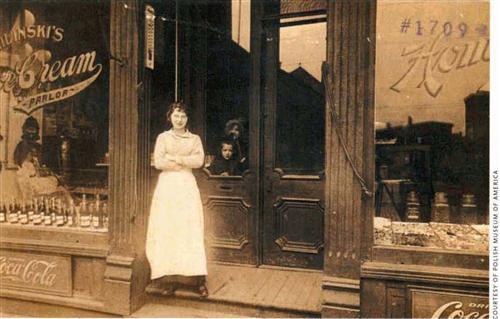

The next wave of settlers to many of these states were the French-Canadian and British fur traders and military. The subsequent migrations were not just east to west, though those trails brought many New Englanders. Many Southerners and others came into and down the Ohio River Valley. Other folks came up the Mississippi from the Port of New Orleans. Still others came across the Canadian-US border, which had no restrictions before the 1890s.

To learn more about the ethnic groups in this region, study individual state and county histories. Publications such as They Chose Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society) detail many of the ethnic groups that settled in Midwestern states.

You’ll need to pay attention to state and county boundaries and formation dates. That geography class you groaned about in school is now of utmost importance! For example, the land that would become Missouri was variously under the control of Spain, France, England and the United States. If you’re researching early pioneers in these states, you may have to look in another state that had jurisdiction over one or more of the others before they were officially established. Early residents of what was to become Minnesota might be found in the records of Illinois, Iowa, Michigan or Wisconsin, depending upon the year. You’ll also see how the rivers and the Great Lakes are important to the settlement and growth of this region. And some counties that once existed are now defunct. You can get help from the many map guides, place-name books and atlases for these states, such as Indiana Place Names by Ronald L. Baker and Marvin Carmony (Indiana University Press, out of print).

It will help if you paid attention in history class, too. The migrations into and out of the states affected the records created in each. The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is extremely different in terrain and population sources from that of southern Illinois, for example. You may find people who think that Upper Michigan was home only to miners and fur traders. Others regard southern Illinois as a Southern state.

Ohio lands present another interesting research twist. Virginians who settled in an area of southwestern Ohio received the land for their Revolutionary War service. But did you know that some of northern Ohio was originally claimed by Connecticut? Many Revolutionary War soldiers and their families migrated into other parts of the Midwest. Most of these states had many residents who served in the Civil War. For Missouri, a number of residents served on both Confederate and Union forces.

A good place to start researching your Mid-western roots, as with any US genealogy, is with the census. The good news is that the federal censuses for these states still exist, for the most part, from the time of their territorial formation. Some early Ohio censuses are no longer available, and the same is true for some individual counties or parts of counties in all these states for particular years. You’ll find printed indexes to the federal censuses for these states for most years and a growing online and CD-ROM collection of indexes and actual census images. The Library of Michigan has a free online index to the Michigan 1870 federal census at <envoy.libraryofmichigan.org/1870_census>; it even includes scanned images of the records.

Many also took state censuses; the majority of these were for years ending in 5. Iowa has stare census records as late as 1925; that census lists everyone in the household. It even gives a county for those born in Iowa and the maiden name of the enumerated person’s mother. Wisconsin and Minnesota have enumerations of everyone in the state as late as 1905. Minnesota Historical Society volunteers and staff members are indexing the 1895 every-name state census. Michigan has an 1894 state census, which tells how many children each woman had and how many were living. The rest of the states don’t include this detail until the 1900 federal census. The 1894 Michigan census is full of valuable information, such as how many years a person resided in Michigan and in the United States.

If you have Ohio, Indiana, Missouri or Illinois ancestry, you won’t have this same good fortune in state census research. Ohio and Indiana have some scattered enumerations of free white males. Missouri has some scattered state enumerations for early years, Illinois has some early state censuses, but many no longer exist. The most recent enumeration is for 1865. That year’s and the 1855 enumeration survive for most counties.

Vital records, online and off

Even though Ohio became a state In 1803 and Indiana followed suit in 1816, neither kept birth or death registrations in its early years. All of these Midwestern states now have state-level vital-records offices. Find out where to write to get vital records at <www.cdc.gov/nchs/howto/w2w/w2welcom.htm>. You’ll find other vital records at the local registrar level. Some larger cities, such as St. Louis, kept separate birth and death records.

During the Works Projects Administration (WPA) years, county and state vital-records indexes were created for some Midwestern states. Checking a variety of library catalogs may yield those for your ancestral areas. You can also find a variety of state, county and local vital records for Midwestern states in the Family History Library (FHL) catalog <www.familysearch.org>. Checking these on microfilm via your local Family History Center will save you some costs of obtaining copies from a government office.

The registration of births and deaths in these states varies by state and by time period. For example, before autumn 1907, roughly half of the births and deaths in Wisconsin were registered. In the 1940s, however, the state health department in Minnesota was still urging local registrars to better comply with laws to register all births and deaths. Marriage records were generally kept in a more orderly fashion and usually begin with a county’s formation or in the years closely following it. Some of the vital records for these states have more than the basic details. For example, some Illinois counties have applications from the bride and groom that list places of birth and the mother’s maiden name.

Increasingly, Midwestern vital-records indexes are being posted on the Web. For Illinois, you can click on a statewide death index for 1916 to 1950 <www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/databases.html>. Once you’ve found an ancestor in the online index, you can obtain birth and death records from 1916 on from the Department of Public Health. Some Illinois counties have scattered earlier birth and death records dating back to the late 1870s. An ongoing statewide marriage index through 1900 is also online at the same site. This effort is the result of cooperation between the state archives and the Illinois State Genealogical Society.

The Ohio Historical Society Web site offers a searchable death certificate index covering 1913 to 1937 <www.ohiohistory.org/dindex>. Additional years are available at the society. In the late 1860s, some Ohio counties; began keeping birth and death records. By late 1908, the responsibility of keeping these records fell under the jurisdiction of the state, which provided copies of birth and death records to the counties. The Wisconsin State Genealogical Society has an online index to Wisconsin delayed and affidavit birth registrations from before Oct. 1, 1907 <www.rootsweb.com/~wsgs/delayed_birth.htm>. The Minnesota Historical Society hosts an online index to death certificates covering 1908 through 1996 <people.mnhs.org/dci/search.cfm>.

Iowa’s vital records begin in 1880, although some county records predate this. Indiana has birth and death records at the county level from the early 1880s on, but these don’t include everyone. The state department of health has birth records from 1907 and death records from 1900. Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > offers subscription access to databases of many Iowa marriages up to 1850 and from 1851 to 1900.

Michigan researchers will appreciate the ongoing Genealogical Death Indexing System that currently covers 1867 to 1897<www. mdch.state.mi.us/PHA/OSR/gendis/search. htm>. Data entry is being done by genealogists across the state.

Missouri has been steadily recording birth and death records at the state level since 1910. Before 1881, a marriage could be recorded at any Missouri courthouse; after that time, you’ll find it in the county where the couple got their license. A database of Missouri marriages to 1850 is available on Ancestry.com.

Indiana researchers can thank the WPA for its extensive work indexing the state’s births and marriages. Today, you can search this data, covering 1880 to 1920 for births and 1845 to 1920 for marriages, on Ancesrry.com, along with a separate database of marriages to 1850.

State archives and historical societies throughout the Midwest offer many online and in-house databases, covering not only the vital records noted above, but also military service and biographies. The ones mentioned here are only the rip of the iceberg — you can find more via the US GenWeb site <www.usgenweb.org>; others are hosted at commercial sites such as Ancestry.com.

For example, the Illinois State Archives’ Web site has a long list of military databases related to service in different wars, going back ru the War of 1812. The state archives and historical society have in-house indexes to many local histories. Indiana researchers should use the Indiana Biographical Index, which catalogs many published items. This tool and many of the books it indexes are found in large libraries. Iowa members of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR — that is, Union soldiers) are listed in a vast microfilmed index. Many of the actual GAR post records have also been filmed.

A detailed Michigan County Clerks Genealogy Directory is online at <www.michigan.gov> (type Michigan County Clerks Genealogy Directory in the search field). You’ll find earlier editions of this directory in booklet format in many libraries. The Minnesota Historical Society has several military indexes and indexed 1918 alien registration records. The Iron Range Research Center <mndiscoverycenter.com/research-center> in Chisholm, Minn., offers census records for several states, as well as a statewide naturalization index for records of Minnesota’s 87 counties.

The Missouri State Archives has published a useful Guide to County Resources on Microfilm, which is also searchable online <www.sos.state.mo.us/Countylnventory>. This tells what records the archives has for each county; the records arc available for sale on microfilm and at the FHL in Salt Lake City. World War I military service cards for 145,000 Missourians have been indexed online at <www.sos.state.mo.us/ww1>. The database entries may tell your serviceman or-woman’s place and date of birth. Ohio researchers will appreciate the microfilmed 450,000-person, every-name index to the biography sections of Ohio county histories. The Wisconsin Historical Society has online searchable local history and biography articles that cover 1850 to 1950 <www.shsw.wisc.edu/wlhba>. Here, you’ll also find the Wisconsin Name Index, which includes references to thousands of obituaries and county history entries.

Many of these states are posting lists and indexes relating to Civil War and other service-related materials on the Web. You’ll find state, local and regimental histories in most historical societies, and some are actually online. Keep checking, as new material is being indexed and digitized all the time.

Each of these states also participated in the US Newspaper Program to identify, locate, catalog and preserve newspapers across the country. See <www.neh.gov/projects/usnp.html> for links to information for each Midwestern state, including newspaper titles and places where you’ll find copies. Most of the Midwestern states’ newspapers are now on microfilm and are available through interlibrary loan. The Illinois and Michigan projects are in progress.

Remember, too, that the Wisconsin Historical Society has the country’s largest newspaper collection, after the Library of Congress. Its holdings include newspapers for Wisconsin, of course, but also for other states.

The Midwest, with its progressive tradition and historical commitment to education, is rich in libraries, historical societies, archives and special collections filled with materials helpful to family historians. Be sure to call ahead or check the Web site of each one you plan to visit to determine hours, fees, parking and other details before you go. You can find online or published guides to many of these repositories’ holdings. For example, check the Minnesota Historical Society’s Genealogical Resources of the Minnesota Historical Society: A Guide, or Chicago and Cook County Sources: A Guide to Research. Another city-type guide is Guide to Genealogical Research in St. Louis.

Several Midwestern states have statewide networks of research repositories that house records related to a county or group of counties. These may include both governmental and private records, though coverage varies by state. For instance, the Illinois Regional Archives Depositories (IRAD) house county records; the state archives Web site <www.cyberdriveitlinois.com/departments/archives/irad/iradhome.html> lists repositories and their holdings. Minnesota has Regional Research Centers, while Ohio has the Ohio Network of American History Research Centers. Wisconsin has Area Research Centers (ARC); the Wisconsin Historical Society Web site has details and links to their sites <www.wisconsinhistory.org/archives/arcnet>.

The Library of Michigan houses the Abrams Foundation Historical Collection, as well as other significant research resources. It has online and in-print discussions of many of its holdings at <www.michigan.gov> (type Abrams Foundation Historical Collection in the search field). The Burton Historical Collection at the Detroit Public Library is a treasure trove for researchers with Detroit and Michigan interests.

The Wisconsin Historical Society library’s materials cover the United States and Canada. Much or its collection is housed in open stacks that researchers can browse. Iowa has two locations for its state historical society. Some items, such as censuses and newspapers, are found at both locations. Each has its own specialties, as well: The Iowa City location offers many personal, organization and business manuscript collections, while the Des Moines location has the state archives. The Iowa Genealogical Society library is another gem for researchers.

In Ohio, the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County has a renowned History and Genealogy Department. The Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland is also well-known. At these two places, you can research far beyond Ohio. Similarly, the Newberry Library in Chicago has some great Chicago resources, but the holdings cover much more than its host city. And the Mid-Continent Public Library in Independence, Mo., boasts one of the nation’s best genealogy collections. In Fort Wayne, lnd., the Allen County Public Library’s genealogy department is another public library that’s home to materials related to all states, plus foreign resources.

The Minnesota Historical Society has a wealth of county and local resources, many indexes and the state archives collection of local and state government records. Chisholm, Minn.’s Iron Range Research Center is a vacation spot: You can take your relatives or friends along on your research trip, and they can view the mining exhibits, listen to oral histories and visit an open-pit mine while you check out the research area. Also in Minnesota, the Immigration History Research Center in Minneapolis serves many ethnic groups. It focuses on peoples from Eastern, Central and Southern Europe and from the Near East who settled in Midwestern states. Much of the collection is foreign-language material.

The Swenson Center at Augnstana College in Rock Island, Ill., is the nation’s leading repository for Swedish immigrant research. It’s the only place outside of Sweden where you can access the fruits of a vast microfilming project of Swedish-American church records. If your Midwestern roots stretch back to Norway instead, head for the Vesterheim Center in Madison, Wis.

The Midwest is a religiously diverse region. Most of the church records remain with individual churches if they are still operating. Some older records or microfilmed records might be found at a historical society or a religious archive. The FHL has many church records for these states, but certainly not all. Among the region’s religious archives is the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, near Chicago. Its Web site <www.elca.org/os/archives/geneal.hftffl> outlines research and access policies. If you can’t go in person, most of these repositories offer research services for a fee or have lists of area researchers for hire. The National Archives and Records Administration also has many resources for these states. Many are in Washington, DC, and others are at regional locations. For the Midwest, check the regional archives in Chicago and Kansas City.