Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Tulips. Windmills. Wooden clogs. Some things are patently Dutch — including the many Americans who can claim Dutch ancestry. Millions of US residents can trace their lineage back to the Netherlands, and even more have roots in the Benelux region of Europe. The area — which comprises the Netherlands, Belgium and the duchy of Luxembourg — gets its name from a 1948 customs union between the three governments. These countries may be more recognizable as the northern part of what was commonly known as the Low Countries, a small cluster situated along the coast of northwest Europe.

Don’t let the size of these countries fool you, though — finding your Benelux ancestors can be tricky. With records scattered throughout towns and parishes, a number of multilingual provinces and a history of shifting borders, the tiny Benelux countries can throw plenty of wrenches in your research. But don’t count them out: Finding your family tree in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg is all a matter of knowing where to look and what, specifically, to look for.

Before you dive into heavy-duty Benelux research, you should first break out an atlas or map to get a feel for the area. Here’s a quick geography lesson: Luxembourg is bordered on the east by Germany, on the south by France, and on the west and north by Belgium. Germany also borders Belgium on the east. France is to the south, and the North Sea is to the west. The Netherlands is on Belgium’s northern border. Of the three countries, the Netherlands has the longest coastline — it constitutes the western and northern borders of the country commonly called Holland; Germany borders it to the east (see the map on page 47). Knowing the general geography of the region — along with the political history that led to the present-day Benelux borders — will help you pinpoint your ancestors’ homelands and give you a jumping-off point for hunting down their records.

Getting in Dutch

Dutch immigrants have been coming to America since the 1600s, and they’re the biggest group to emigrate from the Benelux region to the United States. Today, approximately 6 million Americans claim predominantly Dutch ancestry, and another 12 million have at least some Dutch forebears. Among them are three US presidents — Martin Van Buren, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt — as well as Thomas Edison, Herman Melville and Walt Whitman. Immigrant traffic from the Netherlands to America was heaviest in the 17th century, the 1830s and ’40s, and the period just after World War II.

Many of the earliest Dutch emigrants settled in what’s now New York state — an area colonized by the Dutch West India Company and known as New Netherland in the 1600s. If your Dutch ancestors came during the 1800s, they most likely settled in Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois or Iowa, and chances are they came from the rural villages of the Netherlands. In particular, a large migration from the Friesland area occurred in the late 19th century — the local people, called Frisians, left because of a depression in their economy. The most recent wave of Dutch arrivals — those who came to America after World War II — ended up in the Midwest (specifically Chicago) and the Pacific Northwest. These Netherlanders emigrated as a result of the country’s devastation from Nazi occupation, as well as natural disasters, such as floods in the farmlands.

With the exception of this post-World War II period, Dutch emigrants didn’t undergo forced migration: The Netherlands didn’t suffer from crop failures and societal problems like so many other countries in the mid-1800s. As you discover the localities your Dutch ancestors came from, you may find that they were encouraged to migrate because of economic or religious influences within that specific region.

Even though New York was known as New Netherland in the 1600s, only 70 percent of the immigrants who settled there actually traveled from the Netherlands. Many of those Dutch settlers made the journey because of pressure from the Dutch government or the Dutch West India Company. Like other immigrant groups, some early Dutch settlers came from poorhouses and orphan asylums; some were day laborers or were unemployed. In the 1600s, families weren’t eager to brave the dangers of crossing the ocean, carve out a new beginning in the untamed wilderness or defend themselves against Native American hostilities in order to settle a new colony.

The United States would see an almost continuous influx of Dutch from the 1600s to the 1900s, although a marked decrease in immigration occurred after 1664, when England seized control of New Netherland and gave the area its current moniker. You’ll find that the families of the Dutch who remained there were usually large. It wasn’t long before Dutch settlers began looking for new land upon which to raise those families, spreading out across New York in the 1700s.

When you’re researching your Dutch ancestors, remember that you may also hear them called Hollanders or Netherlanders. And be aware that if you find your ancestor referred to as a Frisian, you’re actually working with four possible provinces of descent: Two of them — West-Friesland and Friesland — are in the Netherlands, while the other two — East- and North-Friesland — are in Germany.

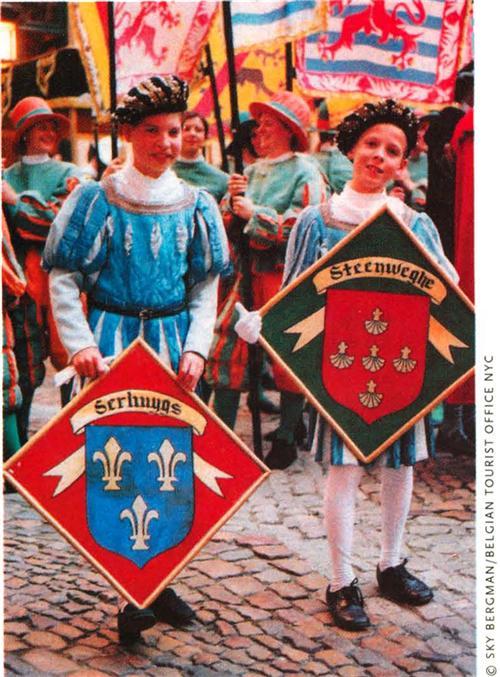

Building Belgium

As a kingdom, Belgium has no history before the 1830s. As individual territories, though, the 10 counties and duchies that make up present-day Belgium have a long and varied past. From 57 BC until it became its own country in 1831, Belgium has been under the rule of the Romans, the Franks, France, the Hapsburg Empire, Spain, Austria and the Netherlands. From 1555 to 1648, it was considered the Spanish Netherlands, and from 1713 to 1795, it was known as the Austrian Netherlands. Not until an 1830 revolt was it recognized as an independent entity, the Kingdom of Belgium.

As you research, you’ll need to keep in mind the 10 individual counties and duchies that — in whole or in part — make up present-day Belgium: the County of Flanders (lands now found in Belgium, the Netherlands and France); le Tournaisis (lands now entirely in Belgium); the County of Hainaut (lands now in Belgium and France); the Duchy of Brabant (lands now in Belgium and the Netherlands); the County of Namur (lands now in Belgium and France); the Prince-Bishopric of Liege (lands now in Belgium, the Netherlands and France); the Duchy of Bouillon (lands now entirely in Belgium); the Duchy of Luxembourg (lands now found in Belgium, Germany, France and Luxembourg); the Duchy of Limburg (lands now in Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany); and the Duchy of Juliers (lands now in Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany).

With Belgium’s complex history and proximity to so many other countries, it’s no surprise that its population today encompasses multiple ethnic groups, predominately the Flemish and the Walloons. Approximately 56 percent are Flemish and most of the rest (32 percent) are Walloons. The remaining 12 percent belong mostly to a small German-speaking population along the eastern border. While the Flemish don’t speak actual Dutch, their German derivative is almost indistinguishable from the Dutch language. The Walloons speak French. These two languages crop up most frequently in Belgian records, though some German may show up in records from the eastern border area. Although Belgians don’t all speak the same language, they do practice the same religion: The country’s almost entirely Roman Catholic.

Despite its size, Belgium has numerous small towns and villages — far too many to search individually. So learning your ancestors’ town of origin is crucial. You may need to get creative with the types of records you check: Look for biographical sources, including obituaries and published directories of different professions. Native-language newspapers — especially ones published in the 1800s — might prove helpful, too. Passenger lists didn’t list the place of birth until the 1900s, but you might get lucky with naturalization records. Death records typically don’t cite specific localities, just that the person was born in Belgium. If your ancestors referred to themselves as Flemish or Walloon, that will help narrow your search.

Before you can cross the ocean, however, you need to thoroughly research your Belgian ancestors in the United States. Most Belgians who came to America emigrated through the port of Antwerp between 1840 and 1900. Upon arrival, the majority settled around Lake Michigan in Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana and especially Michigan. Others settled in Iowa, Pennsylvania, New York and Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, they concentrated in the towns of Lowell and Lawrence, where they settled into existing immigrant communities rather than creating their own. Belgian immigrants tended to seek rural communities — they were trying to leave industrialization behind, hoping to find fertile farmland.

Looking into Luxembourg

Looking into Luxembourg

At a mere 999 square miles, Luxembourg is one of Europe’s tiniest countries; it’s also one of the youngest — if you look only at the time it’s been an independent duchy. The region’s history actually traces back to the 10th century. Since then, Luxembourg has been occupied by the French, belonged to the German Confederation and been caught between its Benelux neighbors. During the 1830s, Luxembourg sat in limbo while Belgium and the Netherlands decided how to carve up its lands between them. Then, in 1839, a large portion of the country became the province of Luxembourg in Belgium, and the remaining area became an independent state. Not long after that, however, Luxembourg again found itself caught between great powers: Napoleon III saw the duchy as his way to offset Prussia’s growing influence; Prussia, in turn, wound up occupying Luxembourg. It wasn’t until May 1867, when the European powers gathered in London, that Prussia was forced to withdraw, and the duchy’s neutrality was finally established.

Emigration from Luxembourg to the United States began in the 1840s, with the largest influx arriving between 1894 and 1914. An estimated 100,000 Luxembourgers and their descendants live in the United States today. Unlike the Netherlands, emigration from Luxembourg was a result of devastating famines. America became known as the “promised land,” where Luxembourgers hoped to find prosperous new lives. And like many from the Benelux region, the roughly 72,000 Luxembourger emigrants settled primarily in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin. The 1920 US census identified about 43,000 Americans as Luxembourgers.

As a result of political changes in the 1800s, many immigrants who came from what’s now recognized as the duchy of Luxembourg were identified as Belgian, Dutch, French, German or Prussian. Here again, it’s important to identify exactly where your ancestors originated, so you don’t spend a lot of time searching the wrong country’s records.

Recording Your Heritage

All those boundary changes will have an impact on your genealogical research — they affected what kinds of records were kept and where you’ll look for them. Study your ancestral group’s history, especially with groups such as the Frisians and Luxembourgers; otherwise, you may go astray in your initial research.

The good news about researching your Benelux roots is that many different record types exist, and most cover even the earliest years of migration. Another bonus: A large percentage of those records have been microfilmed by the Family History Library (FHL), which makes them available to you through your local Family History Center. From the FamilySearch Web site <www.familysearch.org>, you can search the FHL catalog (FHLC) for the following records:

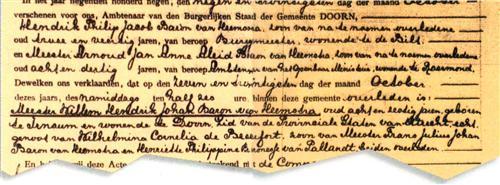

• Civil registration: Birth, marriage and death records are a staple of any genealogical research. Known in the United States as vital records, in many European countries — including the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg — they’re known collectively as civil registration. That’s the subject term you need to look for in the FHLC.

To track down your ancestors, you’ll need to know more than just the country they came from. Neither Belgium nor the Netherlands has a central repository for its civil records; you have to look in the town where the birth, death or marriage took place. The same is true when you’re looking for these records on microfilm — they’re organized by town. Luxembourg has moved its pre-1979 records to the state archives, but again, you need to know the town where the event took place. In the Netherlands, civil registration for the southern provinces began in 1795, and the northern provinces in 1811. Belgium’s civil records began in 1796, and Luxembourg’s go back to 1795. Many of the town records in all three countries are available on microfilm.

• Church records: Don’t give up when you hit the end of the road with civil records; you’ll probably find that church records continue back another century or more. Of course, in addition to identifying the town in which the event took place, you’ll also have to track down the parish. You may need to look in a few parishes to find your ancestors. And keep in mind that some larger towns have more than one parish church.

An overwhelming majority — 97 percent — of Luxembourgers were Catholic, as were most people living in Belgium, so you’ll likely be working with Catholic registers. Still, it’s a good idea to be familiar not only with your ancestor’s religion here in the United States, but also the history of religion in the country from which he came. For details about Dutch church history, see the Netherlands Research Outline on the FamilySearch Web site (from the home page, click the Search tab, Research Helps, then N for Netherlands).

Belgian church records were deposited in the state archives, at least up until the start of civil registration in 1796. Likewise, you can find microfilmed copies of parish registers in Luxembourg’s national archives; the originals are still housed in the individual churches. As with its civil registration, the Netherlands’ church records aren’t archived in a central repository; you’ll have to look in the specific locality. And once you’ve found them, you may run into language hurdles: Some Catholic registers are in Latin, while Lutheran records are usually in modern German or the old German or Dutch script. For help deciphering those old scripts, download the FHL’s German Gothic handwriting guide from FamilySearch (click the Search tab, Research Helps, then G for Germany), or see If I Can, You Can by Edna M. Bentz (self-published).

• Census records: Genealogists often turn to the census to get an overview of a family unit. Belgian census records begin in 1846, but unfortunately, these records aren’t open for public research. A few earlier, more localized directories — for the city of Namur and the province of Brabant, specifically — exist and are available to the public.

In Luxembourg, censuses have been taken every 10 years since 1793; the records are now housed in the national archives. The Dutch began taking a national census in 1829, and took head counts every 10 years until 1850, when similarly formatted population registrations replaced censuses. Researchers will need to visit local municipal archives to access the publicly available census records for the Netherlands, even though the records are national in scope. The FHL has microfilmed a small portion of each country’s census records, but the civil and parish registers usually are more helpful to your research.

• Notarial records: All three countries have notarial (court) records, which cover everything from marriage contracts to property rights. The FHL has many Dutch notarial records on microfilm; look in the FHLC under the province and town in question. Unfortunately, none of the notarial records in Luxembourg’s archives have been microfilmed, so you’d have to visit the archives in person or hire a researcher living there. For Belgium, check the FHLC under Court Records and other headings. You’ll need to know where the event took place if you want to find useful records.

Lowering the Language Barrier: Deciphering Tips

Keep in mind that you might encounter some language hurdles. The FHLC generally lets you know which languages records are written in, but you may find more than one language listed. Luxembourg, for example, offers 10-year indexes composed in French for many of its towns, while many of the actual town records are in German.

Don’t get frustrated if you don’t read or speak the language. The FamilySearch website offers genealogical word lists in Dutch, French and German, which should help you decipher the records most of the time. If you’re going to be spending a lot of time with a particular country’s records, though, you might want to invest in a translation dictionary.

Guidebooks can help you overcome language roadblocks and record-availability detours. Angus Baxter’s In Search of Your European Roots, 3rd edition (Genealogical Publishing Co.), introduces a wealth of records and repositories, and The Family Tree Guide Book to Europe (Betterway Books), coming in November, walks you through how to find relevant records, Web sites, genealogical societies and archives.

Just because your research trail leads to foreign lands doesn’t mean your search has come to a standstill — be glad you can trace your immigrant ancestors back so far! With time and a little flexing of your research muscle, you’ll get a handle on what records exist in your ancestors’ homeland. The language differences might slow you at first, but after a few hours in front of the microfiche machine, you’ll start to recognize the important words. In the end, you’ll look at your family tree with pride — and admire the ancestry that makes you patently Benelux.

A version of this article appeared in the October 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated September 2024.

Looking into Luxembourg

Looking into Luxembourg