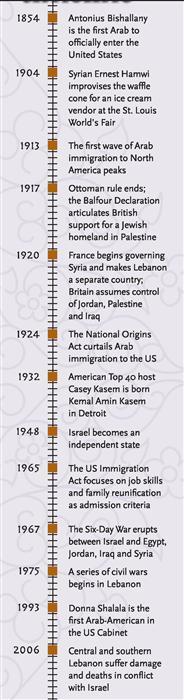

If you have Middle Eastern heritage, your connection with the Western Hemisphere goes back much further than your ancestors’ first landing on American shores. It stretches back even earlier than 1777, when Morocco was the first nation to recognize the nascent American government, or 1492, when Columbus set sail with an Arab translator in anticipation of meeting East Indians. Some petroglyphs and ancient writings archaeologists have found in the US Southwest bear similarities to hieroglyphics and Arabic letters from the same era — suggesting Phoenicians and Northern Africans may have beaten Columbus to the punch by at least 2,000 years.

These early contacts set a standard of sorts for the Arabs who began settling here in the 1870s, and it applies today to most everything in Arab family history: Defy expectations. Ninety percent of early Arab immigrants to North America weren’t Muslims, but Christians from the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholic churches. Many came from Greater Syria, with liturgical languages including Greek and Syriac as well as Arabic. Even the meaning of Arab is up for debate. Some use it to describe a native Arabic speaker from Syria, Lebanon, Algeria or another traditionally Arab country in the Middle East or North Africa. But others point to the region’s many distinct ethnic, cultural and religious groups: Assyrians, Phoenicians, Jews, Copts, Maronites, Syriacs and Druze, among others, some of whom have asserted their non-Arab identities. To further muddy the waters, Maronite and Assyrian immigrants hailed mostly from the rugged Mount Lebanon range above Beirut, and began identifying themselves as Lebanese after World War I, when France carved out Lebanon as a separate state.

Arabs arrived in the United States in two strikingly different waves, the first between 1878 and 1924, and the second after 1965. Those in the first wave had modest means and education. Post-1965 immigrants were usually families and professionals, often Muslim, and from a broader range of Middle Eastern countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Although immigrants in the more-recent wave outnumber their predecessors several times over, the earliest arrivals — many of whose legacies have been lost to time — pose the greater research challenge and are the focus here. Defying those obstacles is worth your effort, and our advice will help you persevere.

Arabic arrivals

The first Arab immigrants settled heavily in the Northeast, especially New York, but quickly penetrated the farthest reaches of the country thanks to the traveling peddler trade so many engaged in. Many filtered out to Texas, California and the upper Midwest, notably Detroit and Cleveland. By 1910, Arab-Americans had reached every state plus Puerto Rico. About 200,000 Syrians and Lebanese lived in the United States by 1924, with smaller numbers coming from Palestine, Iraq and Yemen.

Arab immigrants’ descendants, who number among the 3.5 million Americans with roots in the Middle East, include such all-American figures as Casey Kasem, Ralph Nader, Heisman Trophy winner Doug Flutie and Kinko’s founder Paul Orfalea. They went from being mistaken for Turks by Ellis Island officials to assimilating so thoroughly that, a generation later, white America often assumed their European birthright. The US government perhaps nudged the process along by declining to make official racial or ethnic distinctions — the census counts those of Middle Eastern descent, Arab or not, as white.

Immigrants adapted to their new culture however necessary to survive. For Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience, author Alixa Naff interviewed a Syrian peddler’s wife who joyfully recounted her late husband’s lean days in the early 1900s hiking from town to town with his wares, scraping for every coin and wondering where he’d find a bed. Toward dusk one bitter winter day in Nebraska, he’d been turned down several times for a room when he approached a farmhouse determined to get inside. As a woman opened the door, he pressed his hands together beside his head in the universal sign for sleep and, pretending not to understand her refusal, stepped into the house with a “Thank you.” The man of the house came from the fields, and before anyone could protest, the peddler joined them at the dinner table and said, “Thank you.” The next morning, he approached the woman with three linen handkerchiefs as payment and articulately waxed on about the comfortable lodgings. “But you speak English,” she sputtered. “Yes, ma’am,” he replied, “but if I’d spoken it last night, I’d be out in the cold and frozen to death by now.” They laughed, and he was continually welcomed back.

Shop talk

Whether your parents or your great-grandparents made the journey to America, every good hunt begins with family sources — holy books, letters, vital records, yearbooks and so on. But with Middle Eastern ancestors, so much of what you could learn will come initially by word of mouth.

Iraqi-American Leyla Zuaiter lives with her family in Jerusalem, where she’s worked with cultural institutions to preserve Palestinian heritage. Unlike in the United States, she says, family history is tangible in Palestine. People are reminded of it every time they step out the door in Bethlehem: The city quarters, and even arches and staircases, are named after the original families. With so much history at hand and extended families nearby, people are less diligent about recording the details. Seemingly, there’s always someone around who knows and will talk. “Being Palestinian means never having to say, ‘I have no story,’” Zuaiter laughs. “Eventually someone will mention the cousin from Chile who has the family papers or is compiling the family tree, or an Arabic book that references your ancestors.”

The oral emphasis means Middle Eastern individuals and organizations are less able to furnish resources and documentation, and people in the homeland often have more-urgent priorities and core disadvantages — Palestine, for example, has no book publishers. Stockpiling family information directly from relatives is the most basic and perhaps the best way to overcome such roadblocks.

Sandra Hasser Bennett, a writer and family historian whose father was born in Lebanon, has added to her family tree entirely by working extended family connections. Through a distant cousin, Bennett reached a great-aunt in their ancestral town of Zahle and was rewarded with stories and details about her grandparents. Her challenges, however, have been considerable, starting with the Arabic language. Her father couldn’t write in Arabic, so every time Bennett drafted a letter to a relative in Lebanon, she had to recruit a translator. She tells the story of inviting a Maronite church bishop and her priest to dinner with her parents many years ago. Bennett was shocked when her father carried on an extended conversation with the priests in Arabic — she’d heard him speak his native language only occasionally and never realized he was so fluent.

It takes a little legwork to find distant relatives. Try the Lebanese White Pages <www.leb.org>, a user-contributed directory of more than 45,000 Lebanese around the world. Also network with other genealogists through organizations such as the Southern Federation of Syrian Lebanese American Clubs <www.sfslac.org> and mailing lists such as those at <lists.rootsweb.com> (look for those covering both your ancestral surnames and places).

Arab-American resources

After raiding the closet and buttonholing unsuspecting relatives, trace your Arab ancestors in these US records:

• Census: Search for your ancestors in US censuses (especially those taken after 1900, during the period most Arab immigrants arrived), available in Ancestry.com’s <Ancestry.com > US Deluxe subscription ($155.40 per year) and through libraries that subscribe to HeritageQuest Online <heritagequestonline.com>. You’ll find census microfilm at National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> facilities, large public libraries, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> (as well as its branch Family History Centers).

• Vital records: Arabic immigrants’ post-1900 arrival means access to many of their American-born children’s birth certificates may be restricted. It’s worth a shot, though. To find out where you should write or call, see <www.cdc.gov/nchs/howto/w2w/w2welcom.htm> or a reference such as The Family Tree Resource Book for Genealogists (Family Tree Books) edited by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack and Erin Nevius. The December 2006 Family Tree Magazine gives detailed howtos for digging up birth records.

You’ll usually request death certificates from the same vital-records offices that hold birth records, and you’re less likely to face privacy restrictions. Marriage records often are available from the county clerk’s office where the marriage took place.

• Passenger lists: Ellis Island <ellisisland.org> was Arab immigrants’ main point of entry to the United States; many also arrived in New Orleans. Their ships didn’t necessarily sail straight from the Middle East — French departure ports, such as Le Havre and Marseilles, were common. Search the free online Ellis Island passenger database, or use Stephen P. Morse’s One-Step search forms <stevemorse.org>. Ancestry.com offers access to passenger lists from Ellis Island, New Orleans and many other ports; the lists also are available on microfilm at NARA and major libraries. For 19th-century arrivals, take the nationality information with a grain of salt: Until 1899, US immigration authorities usually classified Syrians as Greek, Armenian or Turkish.

• Newspapers: Like other ethnic groups, Arab-Americans started newspapers for their communities. The first, Kawkab Amrika, hit the presses in 1892 in New York City. In Detroit, Al-Hoda focused on a Maronite audience beginning in 1898; Al-Bayan, first published in Washington, DC, in 1910, targeted Druze immigrants (followers of an offshoot of Islam). By 1919, around 20 papers served Arabic-speaking immigrants. Look for collections of these publications at research and university libraries in areas with large Arabic populations. The University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center holds several Armenian-American newspapers <www.ihrc.umn.edu/research/periodicals/armenian.html>, and its Arab-American research collection includes subscription lists for the Lebanese-American Journal. The Chicago-based Center for Research Libraries holds several Arab-American newspapers on microfilm; you may be able to borrow them from your library through interlibrary loan. Learn more at <www.crl.edu/focus/Arab_American_ Press.asp?isslD=10>.

• Church records: Baptism, confirmation, marriage and perhaps death information may be available through your ancestor’s church. Most first-wave immigrants followed the Maronite, Melchite or Eastern Orthodox rites, all Catholic. Less common were members of Armenian, Chaldean, Coptic, Latine and Syriac churches. In the United States, Maronites established two dioceses (eparchies) in Los Angeles (moved to St. Louis in 2001) and Brooklyn, NY, as well as more than 50 parishes throughout the country. You can look up Eastern Rite churches at <www.opuslibani.org.lb/newdioceses/ant/index.htm> (click the church name at the top, then World on the left). You’ll also find links to many churches at <www.mountlebanon.org/links.html>. Remember, many Syrians and Lebanese didn’t have access to their native Eastern Rite churches, instead attending Roman Catholic or other parishes.

The FHL has some church records on microfilm — run a place search of the online catalog on the town name and look for a church records heading. If you find relevant microfilm, you can borrow it for a fee through your local Family History Center; use FamilySearch to find it. If your catalog search didn’t pan out, try getting in touch with the local church directly, or the area’s diocese if the church no longer exists.

Middle East research

Making the jump to a village or country in the Middle East is a challenge. The usual genealogical records can be hard to come by, whether they’ve been destroyed or rendered inaccessible for political reasons — or never existed in the first place.

But don’t give up yet. “Even if your family emigrated awhile back, once you find one long-lost family member, the rest will probably follow,” Zuaiter says, “especially since first-cousin marriage is common in the Arab world and many families have lived centuries in the same places.” Working through a relative is your best bet for getting church records from your ancestral town. When Andre Dabdoub of Bethlehem took an interest in his family history, he marched over to his family’s local Roman Catholic church in Bethlehem and obtained records dating to 1683 with fields for birth, baptism, confirmation, marriage and death. A fire, alas, prevented him from picking up anything on earlier Dabdoubs, whom he says date to the 15th century.

Civil records are sparse. The Family History Library has microfilmed Ottoman census and population registers of Palestine from 1883 to 1917, in Turkish with an English index (run a keyword search of the online catalog for ottoman census). Women are less likely to turn up in certain civil records, but you’ll occasionally find them in marriage records and Ottoman-era Islamic court records (1517 to 1917), the rough-cut gem of Middle East genealogical research. “The Ottomans are the only civilization that kept these kinds of records,” historian Khalil Shokeh says. A Palestinian, he waited years for a governmental OK before traveling to Istanbul to use the records. They’re remarkably preserved and comprehensive. Notes documenting marriages, divorces, inheritances, custody suits, land sales, civil and criminal cases, taxes and much else appear in the ledgers, providing a detailed picture of lives and society over hundreds of years. Researchers say it’s even possible in some cases to plat out a town’s layout and its residents at a point in time using these records.

To inquire about Islamic court records covering Jordan and Palestine, contact the University of Jordan <www.ju.edu.jo/resources>; for Syrian records, check with the Al-Assad National Library <www.alassad-library.gov.sy/eindex.html>. In Lebanon, records are more decentralized. The Jafet Library at the American University of Beirut <wwwlb.aub.edu.lb/~webjafet> can point you in the right direction. Of course, records are in Arabic and sometimes Turkish script, so you’ll need a translator if you don’t know the language.

Depending where you’re visiting, workspaces can be spare (with the possible exception of large Middle Eastern universities). Printers and copiers are sometimes inoperable, so bring a digital camera to photograph records. Researchers have reported sharing desks with employees or reviewing records in the same room where court is in session. Records access is improving, however, due to microfilming and database projects, and who’s to say some records won’t be available online by the time you’ve located your Middle Eastern ancestors? After enduring all the unforeseen obstacles in your path, that development, most assuredly, would defy your expectations.

From the February 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.