Poland’s history is long and fraught with frustration, and family history researchers are likely to feel some of that same frustration when it comes to seeking their roots. The first king, Mieszko I, ruled in the 10th century. About the same time, the country became part of the Holy Roman Empire. Poland reached its height politically in the late 14th and early 15th century, when the Jagiellonian dynasty united with Lithuania and defeated the Teutonic knights, who had been called in as protectors. The Swedes invaded in the mid-17th century. Then, in 1772, Russia, Prussia (the rough equivalent of today’s Germany) and Austria began the process of slicing up Poland. Despite that first partition, the Poles came up with Europe’s first constitution in 1791; two years later, however, Russia and Prussia took more land and annulled the constitution. In 1795, Prussia, Russia and Austria erased Poland from the map.

Several unsuccessful efforts for autonomy followed, often accompanied by the departure of great minds. For example, after a November 1830 uprising against the Russians failed, Frederic Chopin and the poet Adam Mickiewicz left their Polish homeland. Joseph Conrad, who eventually would write Lord Jim, left after a failed uprising in January 1863. Fed up with Polish feistiness, the Russian and German monarchs implemented severe policies aimed at killing the spirit for independence. Between 1870 and 1914, more than 3.5 million people left what had been Poland for the United States, with the emigration relatively even between those leaving Russian- and German-controlled lands.

There was a brief — 21-year — interlude of Polish independence after World War I. Then, on Aug. 23, 1939, Russia’s Stalin and Germany’s Hitler signed a nonaggression pact splitting Poland. During World War II, 6 million Poles were killed and 2.5 million were deported to Germany for forced labor. All but about 100,000 of the 3 million Jews who lived in Poland before the war died. The atrocities left Poland as one of the most homogeneous countries around; the US State Department estimates 98 percent of the country’s approximately 39 million residents today are of Polish descent, and 90 percent are Catholic.

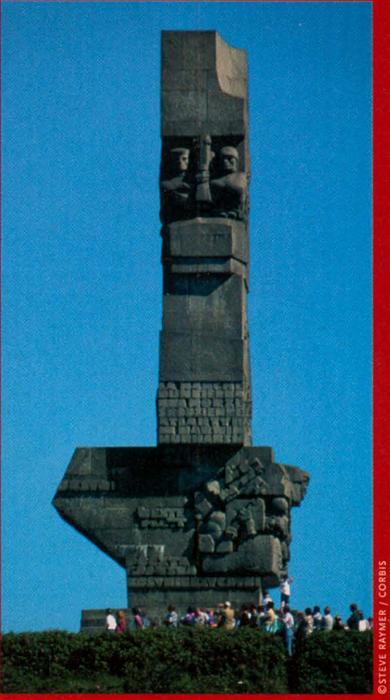

Following the war, Poland was back on the map, as a Soviet satellite country. Then came the dramatic days of 1980-1983, when the Solidarity labor movement was born in the shipyards of Gdansk, and Poles dared hope for freedom again. The first postwar noncommunist government was elected in 1989, and labor leader Iech Walesa became the country’s first popularly elected president the following year.

Crack open your atlas

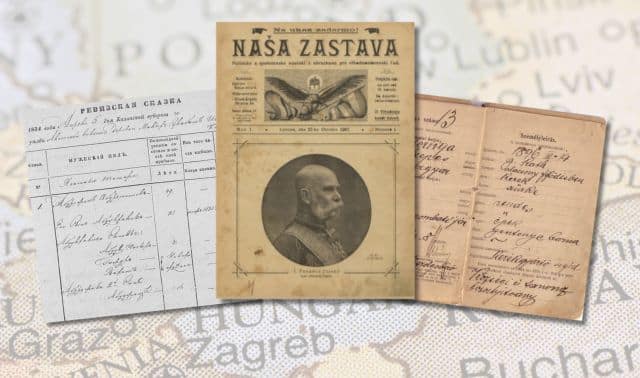

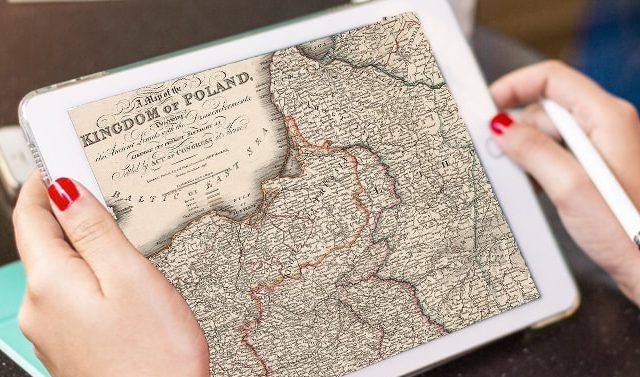

Because of Poland’s troubled past, finding and reading records in the old country can be a nightmare. For example, if your ancestors lived in eastern Poland, records from 1868 to 1917 will be in Russian. Records from 1808 to 1868 generally should be in Polish. As for western Poland, controlled by Germany while Russia ruled the east, records generally will be in German or Latin (the language used by the Catholic Church), although you may find some in Polish. And what of Galicia, the part of the partition ruled by Austria? Most records will be in Latin, although some will be found in German and Polish.

The present is almost as confusing. Poland had 49 wojewodztwo, or provinces, until a January 1999 reorganization. There now are 16. In another complication, the old provinces frequently had a city with the same name as the province; that’s no longer the case.

As in much of European research, knowing the precise city or village in which your family lived is essential, for either civil or church records. If you don’t have a clue based on family legends, interviews or documents, you may be in for a lengthy, perhaps ultimately unsuccessful, search. Without clear, concrete knowledge that a particular record for your ancestor exists, you’d be better off spending some time researching at your local Family History Center before booking your flight to Poland.

Some records simply no longer exist, especially if your ancestor came to the United States by ship. Hamburg and Bremen, both in Germany, were the most popular ports of exit for Poles during the major emigration period. Records are available for those who left from Hamburg; check out <www.hamburg.de/LinkToYourRoots/english/welcome.htm> for a database of 5 million people who passed through the port. The bad news is that twice as many Poles left via Bremen, and those records were destroyed by the German government due to lack of space and by Allied bombing during World War II. A few Poles left via Belgium and the Netherlands; records for those ports are sparse.

You may be in the same boat, pardon the pun, when it comes to checking passenger lists. From 1820 to 1882, only the passenger’s name, age, sex, country of allegiance, destination and occupation had to be recorded. Even after that date, the passenger’s hometown or place of birth didn’t have to be noted. Still, there can be clues in learning who else was on a particular ship: your ancestor’s brother? mother? eventual spouse? Watch for similarly spelled names, or names appearing immediately before or after your ancestor on the list.

While Poles and others streamed into the United States through Ellis Island <www.ellisisland.org> starting in 1892, a significant number also entered before then at Castle Garden in New York City <www.nps.gov/cacl/> as well as Baltimore, Boston, Philadelphia and New Orleans.

Because the Polish migration began relatively early, finding a paper trail on your ancestor’s arrival also can be difficult. Naturalization records became the purview of the federal government in 1906; before that, immigrants filed their intent to become citizens in a variety of courts, sometimes near the city where they arrived. Actual naturalization usually didn’t come for another couple of years. In some cases, those early documents list nothing more than name, country of birth or allegiance and date of application. When you look for records prior to 1922, you’re most likely to find information about male ancestors; women automatically became citizens if their husbands were or became citizens.

Know your feast days

If you turn up a passenger list or naturalization application that looks like it might be for one of your relatives, but the first name doesn’t seem to match, a brief introduction to Polish naming customs may help you establish a missing link.

In many cultures, children are named after grandparents in a relatively easy-to-follow structure (first-born son, paternal grandfather; firstborn daughter, maternal grandmother). Don’t expect that to be the norm when it comes to Polish ancestors, because of the Catholic Church’s influence on everyday Polish life. Children often were named after a saint whose feast day was near the child’s birth or baptismal date. For example, my great-grandfather, known in this country as John Organist, was baptized with the first name Katejan, for an Italian saint whose feast day, Aug. 7, was close to his birthday. His daughter and my grandmother; Mary, was born on Sept. 7, the day before the feast day for the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. You’ll find great lists of saints’ feast days at <www.polishroots.com> and in Polish Roots by Rosemary A. Chorzempa (Genealogical Publishing Co.), generally acknowledged as the best book available on researching your Polish ancestry.

This is also an appropriate place to note that Polish surnames change. Polish is an extremely complicated language, influenced by those centuries of subjugation. The language is Indo-European and similar to other Slavic-languages, with a vocabulary influenced by everyone from the Romans to the Swedes to the Germans and Russians. Surnames change depending on how they appear as a singular subject. In Introduction to the Polish Language (Kosciuszko Foundation), the authors demonstrate how the surname Nowak is spelled nearly 20 different ways, depending on the grammar case and whether the name is being used in the singular or plural and if the Nowak is male or female.

Further, be aware that the Polish alphabet consists of 33 letters (when X, seldom used, is included) and does not include Q and V from the English alphabet. Numerous diacritics (dots, slashes and accents) can substantially change a word’s pronunciation. When consulting old documents, consider the possibility that what looks like an R is in fact a K, or what looks like dz is really dz.

Surnames also changed once your ancestors got to the United States; often Polish immigrants wanting to fit into their new country Americanized their names. And what you think is your family name may be the name of the town from which they came or the estate on which they worked. Polish Surnames: Origins and Meanings by William F. Hoffman (Polish Genealogical Society of America) provides the origins of 30,000 common Polish surnames, categorized by their roots.

Similarly, don’t rule out Americanization of first names if you’re having trouble matching up a relative with census, civil or baptismal records. In our family, for example, Leokadia, the Polish equivalent of Laura, has instead evolved as LaCarda; a great-aunt identified in the 1910 census as Paulina was known to one and all as Pearl. In many cases, the Polish name and the American equivalent (Fryderyk and Frederick, for example) are spelled differently, and the Latin spelling may be different still. It’s up to you whether you enter the name in your family tree as it appeared on an official record or as the person was known. But it’s best to do one or the other consistently, with a notation of the other name.

Desperately seeking pierogi

Even if you never locate records of your ancestors in Poland, you’ll find plenty of opportunities to revel in things polski in the United States. It’s estimated that more than 200,000 native-born Poles live in major US metropolitan areas today. More than 9 million Polish-Americans and Polish immigrants were living in the United States as of the 1990 census — an increase of 1.1 million from 1980 — making them the nation’s ninth-largest ancestry group. Seven states had Polish populations of more than 500,000.

The Polish heart of the United States is in Chicago. The Polish American Association estimates 1 million people of Polish ancestry live in the metropolitan Chicago area, second only to Warsaw in the world. The association counts more than 83,000 Polish-speaking people in Chicago alone and more than 124,000 in Cook County, Ill., where Chicago is located. Within the city, you’ll find real estate agents, travel agents, check-cashing businesses, restaurants and groceries proudly proclaiming that Polish is spoken there. For total immersion into the Polish experience, head up Milwaukee Avenue, where for more than a mile you’re more likely to hear tak and nie than yes and no.

The metropolitan areas of New York City, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Detroit and Buffalo, NY, also have significant Polish populations. Even places like Texas have Polish genealogical societies, reflecting the wave of Poles who came to Karnes and Walker counties in Texas in the second half of the 1800s.

If you’re looking for Poles in your area and can’t find them on the Internet, mark March 19 on your calendar and watch for restaurants that advertise St. Joseph’s Day specials. That’s the Catholic feast day and traditional death day for the Virgin Mary’s husband. It’s a sure bet nearly everyone in the restaurant will be Italian or Polish. Why are those two ethnicities so tied to this particular feast day? Making that March day particularly festive may have appealed to Polish and Italian immigrants following their Irish Catholic brethren’s huge celebrations two days earlier for St. Patrick’s Day. The feast day also provides a bit of a respite from the solemn introspective of the Lenten season. Whatever the reason, in areas where Italians and Poles live, you’ll often find a fine St. Joseph’s table at restaurants and some churches that day, groaning with pierogis, potato pancakes and more, a statue of the saint and a place to make offerings for the needy.

In May, the Polish American Cultural Center in Philadelphia celebrates Polish Constitution Day. Each June, Milwaukee hosts Polish Fest <www.polishfest.org>, which it says is the country’s largest Polish festival. Beyond the usual ethnic food lineup there are a Chopin piano competition, dance classes and a cultural village display.

Also, watch for activities in your area in October, which since 1986 has been celebrated nationally as Polish-American Heritage Month. On the second Sunday in October, there’s a reunion in Panna Maria, Texas, for the descendants of Poles who came to that area.

If all this talk of festivals and events makes you think Polish-Americans are obsessively proud of our past, you’re probably right. But remember, our ancestors fought hard for centuries to keep that culture alive. Celebrating it is the least we can do to thank them.