If you have Polish roots, you’re a member of the largest Slavic group in the United States. You also share the legacy of Polonia, a diaspora that built new communities abroad while the Polish homeland suffered more than a century of foreign occupation.

Today Poland is a country again, but Polonia became permanent for millions of its former citizens. Ten million Polish progeny are Americans, and many of them have begun looking backward at their families’ pathways from Poland.

The stories they encounter vary widely. Some find comforting images of a grandmother in her Detroit kitchen, preparing pierogi for her autoworker husband. Others discover a WWI soldier uncle’s longing for an independent Poland. Still others, grim but grateful, record their survival of the Holocaust and the names of loved ones lost.

Whatever brought your Polish ancestors here, you can retrace their pathways home. Polonian communities in the United States proudly record their heritage, and increasingly accessible Polish records can tell you more about lives lived under Russian, German or Austrian rule. Here’s how to start your own virtual journey back to the Old Country.

Pieces of Polonia

Poles began coming to the United States in large numbers in the 1880s, along with many other immigrants looking for a better life. Nearly 100,000 arrived in the 1890s, over a quarter-million in the 1920s and another 50,000 in the 1960s. They came largely for jobs advertised by industry recruiters and to escape harsh governmental policies at home.

Polish immigrants flocked to Michigan, Wisconsin and Connecticut, but also to other Great Lakes and northeastern states, and even Florida, Texas, Arizona and California (see the map at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/5/5c/Polonia_USA.png). Polish-American neighborhoods grew, with their own religious parishes and schools, benevolent societies and newspapers. Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Buffalo and Cleveland all claimed pieces of Polonia.

These new heartlands can be excellent sources for material on your relatives’ Polish-American experience. Polish genealogical groups in these areas preserve records and ethnic identity. See the Polish Genealogical Society of America for links to such organizations. Local histories capture stories and images, such as those in Chicago’s Polish Downtown by Victoria Granacki (Arcadia Publishing) and the Wisconsin Historical Society’s online article “Fifty Years of Polish Settlement in Portage County[WI], 1857-1907”. A Google search on Polish and your ancestors’ US hometown or state will turn up publications and organizations relevant to your search.

Determining Your Destination

You’re traveling your ancestor’s route in reverse: Your final destination is the exact village from which their pathway from Poland originates. Look to these US sources:

Censuses

US census records can pinpoint your immigrant ancestors’ year of arrival (starting with the 1900 census), help identify a birthplace (beginning in 1850) and report citizenship status (starting in 1900). Parents’ birthplace is requested beginning in 1880. Subscription site Ancestry.com has indexes and images of the entire US census (see if your library offers the free Ancestry Library Edition) and Archives.com is adding them. Many censuses are on the free FamilySearch.org.

Naturalization papers

Post-1906 citizenship papers may give an applicant’s last foreign address and birthplace (married women and children didn’t need their own paperwork until after 1922). Order these records from the US Citizenship and Immigration Service; some are on National Archives and Family History Library (FHL) microfilm. Pre-1906 records, which may reveal only the country of origin, could be in county, state or US district courts. Consult The Family Tree Sourcebook for information on how to request naturalization records for each state or county. Ancestry.com and Fold3 have some naturalizations made in federal courts.

Social Security applications

SS-5 forms start in 1936 for people who registered with the Social Security Administration, and may show a town of birth. You can search the Social Security Death Index on several sites, including FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com. Most names are for deaths after 1961. Request a copy of the SS-5 by mail or online for a fee; see www.ssa.gov/foia/html/foia_guide.htm.

Draft registrations

WWI and WWII draft cards, which even nonnaturalized immigrants had to fill out, request a birthplace in detail—town, state and nation. (Also look for clues in draft registrations of your ancestor’s brothers, cousins, uncles and parents.) Digitized draft cards are on Ancestry.com for both wars. FamilySearch.org has an index for World War II and has begun to post images. You can order $5 copies of WWI draft registrations at eservices.archives.gov/orderonline; click on Order Reproductions. For the same price, order WWII draft registrations from the National Personnel Record Center by mail; see archives.gov/st-louis/archival-programs/other-records/selective-service.html.

Passenger lists

Ship manifests can give an ancestor’s hometown, though you may find just the country or last port-of-call. It’ll help your search to know the arrival year or ship name, plus your ancestor’s proper Polish name, which may be different from the name in US records. Ancestry.com has post-1820 US passenger manifests. Search Port of New York records from 1892 to 1924 at www.ellisisland.org. Also check indexes at immigrantships.net and www.theshipslist.com.

Other US records

Church records, vital records and newspaper announcements of births, marriages and deaths may mention a hometown or relatives whose origins you can research. Local histories also may mention villages from which many local immigrants arrived.

Polish Places

Once you’ve identified your ancestors’ town, plot its location in modern Poland. That’s not as easy as it sounds: Poland is made up of 16 provinces (voivodeships), 379 counties (powiats) and more than 2,000 municipalities (gminas, some of which are large enough to have concurrent powiat status). Records on individuals are generally kept by municipalities. Because records may be in several languages and you’ll be communicating with Polish records custodians, you need two important traveling tools: maps and translating devices.

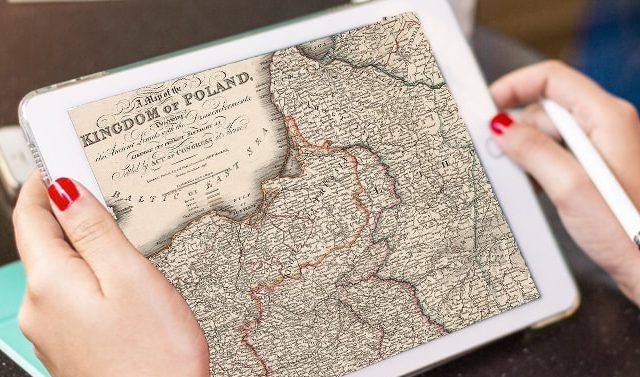

Maps

First, identify your ancestral town on a historical map and then confirm its modern location. You can use online maps; the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny (Military Geographical Institute) is a go-to source for pre-WWII Poland. Between 1919 and 1939, this organization published geographic materials that are now online, along with a Polish-English map vocabulary list. You can order copies free of charge via the Library of Congress’ Ask the Librarian program (click on Geography & Map). Request a specific map (or the village name, longitude and latitude) along with the map key.

If your ancestor lived in a predominantly Jewish village (shtetl), turn to the ShtetlSeeker, a village-seeking tool that uses a Soundex system tailored to Central and Eastern European languages. You’ll also find links to modern maps.

Marco Polo Polska Atlas Drogowy (Road Atlas of Poland) is an excellent modern map series. As a companion tool, you’ll want the First Edition Index to this map, published by Genealogy Unlimited. It references 90,000-plus place names that correspond to cataloging by voivodship for FHL microfilms of Poland.

You also can access a modern city-finder at mapa.szukacz.pl. Even if you don’t read Polish, you can do a place search in the field labeled Miejscowosc, then hit Pokaz (find). Results will appear as circles on a map (the name might correspond to more than one location). See a guide to using this site and other invaluable place-finders in Sto Lat: A Modern Guide to Polish Genealogy by Cecile Wendt Jensen. Find a helpful directory of regional Polish resources at rootsweb.ancestry.com/~polwgw/areas.html.

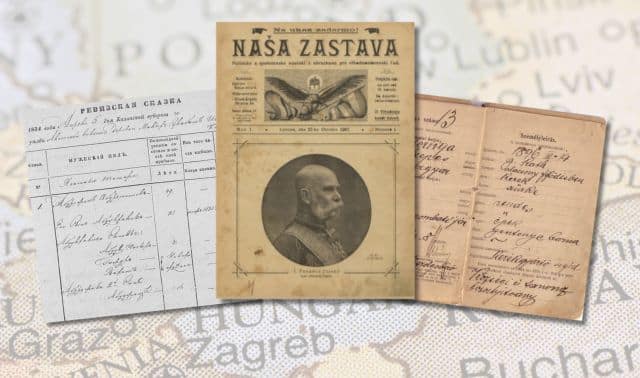

Translation tools

Before 1918, genealogical records may be in Polish, German, Russian or Latin. In Russian Poland, Polish was used in vital records from 1808 to 1868; Russian took over until 1917. In German Poland, you’ll see German or Latin records, with a sprinkling of Polish. Austrian Poland primarily relied on Latin, but you’ll come across German and some in Polish.

For help reading Polish records, consult A Translation Guide to the 19-Century Polish-Language Civil-Registration Documents by Judith R. Frazin (Jewish Genealogical Society of Illinois), free in Google Books (see Family Tree Magazine’s Google Library at snipurl.com/ftm-google-library). Also see Jonathan D. Shea’s Russian Language Documents from Russian Poland: A Translation Manual for Genealogists (Genealogy Unlimited). You’ll find translation tips at the Society for Germany Genealogy in Eastern Europe website www.sggee.org/research/translation_aids and in the FamilySearch Research Wiki (enter the language and word list in the search box).

Letter-writing guides will be vital if you need to write to Polish archives (don’t expect archivists to read English). The Polish Genealogy Project website posts helpful links to letter-writing guides (including FamilySearch’s) as well as tips for understanding records an archives sends back (or why your request isn’t successful).

Homing In on Homeland Records

With these tools in hand, you’re ready to delve into Polish records. Start your search with these record groups:

Religious records

The dominant historical religion of Poland is Roman Catholicism. There were significant Jewish communities in Russian and Austrian Poland, and Mennonites in the Vistula Delta area. Lemkos, who inhabited the Lower Beskid range of the Carpathian Mountains, followed eastern Catholic traditions (learn more at <lemko.org>).

Catholic parish records can include parishioner lists, marriage banns, announcements, religious education rolls, and registers of lay ecclesiastical movements and religious orders. Priests consistently recorded parishioners’ individual sacraments as early as 1547; in 1782, they also began keeping registers of Jews and other non-Christians. Rabbis and ministers of other Christian faiths also recorded births, marriages and deaths.

Four key Catholic church records with rich genealogical details on the person and family members are baptismal records, marriage records, death certificates and burial records (these may reference the churchyard, but not specific plots). Term graves, the tradition of reusing graves, is a common practice in Poland even today; the family pays a leasing fee.

Determine the parish your ancestors likely attended based on their village in Stanislaw Litak’s The Latin Church in the Polish Commonwealth in 1772 or, more currently, Roman Catholic Parishes in the Polish People’s Republic in 1984 by Lidia Mullerowa (both from the PGSA). For southern Poland, turn to Gerald A. Ortell’s Polish Parish Records of the Roman Catholic Church: Their Use and Understanding in Genealogical Research (PGSA). You can order microfilmed copies of most extant parish records through your FHL branch FamilySearch Center or mail a request to local parish offices. Images of church books from parishes in the Czestochowa, Gliwice, Lublin and Radom dioceses are online at FamilySearch.org.

Civil records

Civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths before about 1800 exist most frequently for noble and middle-class families. Beginning in 1804, universal civil registrations were recorded in the Russian partition of Poland under the Napoleonic code; similar records began in the Prussian sector in 1874. You’ll find excellent genealogical information in these records: Birth registrations may name birthdate, time and place; parents’ names, ages and father’s occupation; and grandfathers’ first names. Most civil registrations older than 100 years are at Polish regional archives. The Polish national archives website directs you to regional archives. Click on State Archives, then List of Archives. If you request records, be prepared to pay an hourly rate. Microfilm of most pre-1880 records are available through FamilySearch Centers. An index of Jewish Poles listed in civil records is at www.jewishgen.org/jri-pl.Vital registrations less than 100 years old are in civil records offices at town halls across Poland. Address a request for a typed abstract (photocopies aren’t permitted of these records) to the Urzad Stanu Cywilnego, [town], Poland. Or hire a local researcher to visit the office for you.

Community histories

These are incredibly important in Polish research. The 15-volume Slownik Geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego (Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland) was published between 1880 and 1902. This amazing resource describes every Polish village’s geography, history, government, churches, demographics, history, schools, names of landowners and inhabitants, and more. Sources for further reading are suggested for each village, too. Find it online at dir.icm.edu.pl/pl/Slownik_geograficzny.

Yizkor books published by former residents of European Jewish communities pay tribute to their hometowns and Holocaust victims. The JewishGen Yikzor Book Project maintains a database listing all known books. Search under your ancestor’s town and region at www.jewishgen.org/yizkor, then check other areas of the website for available print and web versions, translations, mentions of your ancestors in the necrology index, etc. You also can read digitized versions of 650 yizkor books at the New York Public Library at legacy.www.nypl.org/research/chss/jws/yizkorbookonline.cfm.

Ship departures

Poles most frequently departed from Bremen, Hamburg and Stettin, Germany (Stettin is now in Poland); and to a lesser degree, Antwerp and Rotterdam, Netherlands. Some traveled by land and ferry to England and departed from a British port.

Seven million emigrants sailed from Bremerhaven between 1832 and 1974. Unfortunately, lists from 1875 to 1908 have been destroyed, and all but about 3,000 lists for 1920 to 1939 were lost in World War II. Surviving lists are indexed at www.passengerlists.de.

Hamburg Direct and Indirect Passenger Lists and Indexes (1850-1934) are on microfilm through FamilySearch Centers and on Ancestry.com. The database is indexed for 1885 to 1914; browse handwritten indexes for the 1855 to 1934.

Manifests for Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland) also are fragmentary. Surviving departure lists for 1871, 1876 to 1891, and 1896 to 1898 are in the Vorpommersches Landesarchiv in Greifswald, Germany.

The search for these records may be a long, winding road. But chances are good you’ll discover the ghosts of traveling companions along the way—like that freedom-fighting uncle—who will introduce you to long-gone relatives in Poland. That’s the best thing about travel: the people you meet.

Free Web Content

A version of this article appeared in the January 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine.