Did your ancestor serve in the US military during the Revolutionary War, War of 1812 or Civil War? If so, look for a pension record related to his service. Military pension records are some of the richest family history resources available, often containing information not found anywhere else.

Access to these potential treasures has grown easier as online databases and digitized records bring more pension indexes and files to our fingertips. This workbook will arm you with the knowledge you need to scout out and capture your ancestor’s pension file. We’ll also examine records for each conflict, run through some quick drills and provide a worksheet to help track your research.

Clues in pension records The US government issued pensions under various conditions, which changed over time. Disabled veterans applied for invalid pensions, documenting their physical hardships. Widows of men who died of war wounds applied for widows’ pensions, citing loss of support for themselves and their children. Veterans and widows who lived long enough applied for service-based pensions when new laws made them eligible.

The government, hesitant to hand out money on word alone, required proof that the applicant qualified for benefits. This often created thick files of affidavits, letters, service confirmations, marriage records, physical examinations and more.

Not every man who served in the military from 1775 to 1865 received a pension. A veteran or his survivors had to qualify under existing laws, file applications with the necessary documentation, and be approved by the government to receive benefits. These steps were laden with difficulty.

Pensions based on service, rather than death or disability, were generally unavailable until decades after the conflict ended. As a result, many veterans died before they could apply. In addition, some early pension records have been lost.

Most pension files include personal and military information. Civil War files tend to be larger than files from earlier wars. In a typical veteran’s file, you might find:

• the soldier or sailor’s full name

• his rank and the name of his company, unit or ship

• his date and place of enlistment

• his age and residence at time of enlistment

• his term of service or date of discharge

• his date and/or place of birth

• his residence at time of application

• descriptions of his service, wounds and claims

• testimonies of comrades, friends and neighbors

If a soldier applied for a pension, and then his wife applied for a widow’s pension after his death, you’ll find the files together. Most widows’ files hold genealogical data such as:

• the widow’s maiden name

• her date and/or place of birth and death

• her age and residence

• the date and place of her marriage to the soldier

• names and ages of their living children

• birth dates of minor children

• information about any previous marriages

• the veteran’s date and place of death

This information, usually scattered throughout a file, can point your research in many directions. The date and place of enlistment can help you identify your ancestor in census, land and tax records. Birth information opens possibilities for finding parents. Marriage and death dates can substitute for missing vital records. An elderly pensioner’s file might help you trace the family’s migration over a lifetime.

Because pension files contain more personal details than compiled service records, seeking out the pension first helps you make sure you have the correct person. From the pension, you’ll get the information you need to find the right service record, any bounty land warrants granted and associated records like pension ledgers, vouchers and last payments.

Finally, the affidavits of comrades, relatives and neighbors give you a glimpse into the pensioner’s circle of friends. Their statements help you reconstruct the family and understand events. Not only can this lead you to additional records, it brings the story of your family’s wartime and postwar challenges, joys and heartbreaks to life.

Revolutionary War pensions After the American Revolution, the new US government was land-rich and cash-poor. Prior to 1818, veterans of the Continental Army and state militia units were more likely to be compensated with bounty land grants than with pension payments. Pensions were initially restricted to officers, severely disabled veterans, and widows of men who died in the war. Unfortunately, nearly all of the earliest pension files were destroyed in a War Department fire in 1800. Another fire in 1814 claimed more records.

An 1818 act granted service pensions to men who’d served in the Continental Army or Navy for at least nine months. Response was so great that two years later, a new law required applicants to show financial need. Not until 1832 were benefits extended to anyone who’d served at least six months in Continental forces or a state militia. By that time, the ranks of survivors were thinning rapidly. Laws governing widows’ pensions became more generous starting in 1836.

Surviving Revolutionary War pensions are at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC. They’re alphabetized and microfilmed (see NARA microfilm M804). A finding aid, Index of Revolutionary War Pension Applications in the National Archives, is in many libraries.

In addition, the files are now digitized, indexed and available at subscription sites Fold3 and Ancestry.com, and free at FamilySearch.org.

A collection of selected records from NARA microfilm M805 draws from the same set of files, but contains no more than 10 pages deemed to have the most genealogical value from each file. HeritageQuest Online, accessible via subscribing libraries, has digitized and indexed this film.

Several other online collections can enhance your Revolutionary War pension research. Ancestry.com’s database “American Revolutionary War Rejected Pensions,” includes rejected application files, and the “U.S. Pensioners, 1818-1872” database contains Treasury Department pension ledgers describing payments made to veterans and widows. These ledgers are helpful in tracking migration and may name heirs.

The same records are in the FamilySearch’s unindexed database “United States Revolutionary War Pension Payment Ledgers, 1818-1872.” Fold3 has the “Final Payment Vouchers Index for Military Pensions, 1818-1864,” a finding aid for locating the last payment made to a veteran or to his heirs. It’s particularly valuable for identifying relationships.

War of 1812 pensions The War of 1812 utilized seamen on the Atlantic coast and Great Lakes, regular Army troops and local militias organized by county and state. After the war ended in 1815, the federal government—which had not yet begun issuing service pensions for the Revolutionary War—wrestled with how to compensate these men.

The first post-War of 1812 acts offered half-pay pensions to widows and orphans of men who’d died in action or from wounds incurred during the war. The family received half of the monthly pay their soldier or sailor was entitled to for a period of five years, later extended to 10. Veterans who’d sustained disability also could apply for invalid pensions.

Nearly 60 years after the War of 1812 began, its veterans and their widows finally became eligible for service pensions under the Acts of 1871 and 1873. Restrictions on the length and type of service, and date of marriage if a widow, limited the number of applicants. The Act of 1878 lifted the restrictions and granted pensions based on as little as 14 days of service.

Regular Army death and disability applications comprise part of NARA’s “Old Wars” series of pension files, which also includes records from the Mexican War and various Indian wars. The files haven’t been microfilmed or digitized, but you can search digitized index cards at FamilySearch.org. See directions below for ordering the files from NARA.

War of 1812 pension application files also are arranged alphabetically at NARA. An index of file jacket envelopes is on microfilm (M313) and online in the Ancestry.com “War of 1812 Pension Application Files Index, 1812-1815” database. A second and smaller index, known as the Remarried Widows’ Index, is on microfilm (M1784) and online at FamilySearch.

Digitization efforts to bring the War of 1812 pension files online are underway. The Preserve the Pensions project will make free digital images available on Fold3. Imaging has started alphabetically. Check the database for your ancestor’s record if his surname begins with letters A through G. At present, most files must still be ordered from NARA.

Because land was the preferred compensation for servicemen until the mid-1800s, always look for a bounty land warrant for your War of 1812 ancestor. Our Land Records Workbook helps you find federal land warrants and patents. Some veterans’ bounty land papers were consolidated into their pension files.

Civil War pensions The Civil War pulled an unprecedented number of American men into military service. Even before the war ended in 1865, parents, widows, orphans, and wounded men looked to their governments for relief. Both the federal government and former Confederate state governments responded.

Union soldiers

Volunteers and draftees bolstered Union forces. As these men and their widows aged and new laws took effect, pension rolls swelled into the 20th century. The first pension law for Union widows, orphans and disabled soldiers was enacted in 1862. Later acts were less stringent, but until 1907, death and disability were the only grounds for a pension. The Act of May 11, 1912, granted service-based pensions to most veterans of the Civil War and Mexican War. Widows’ compensation became more generous in 1916 and 1920.

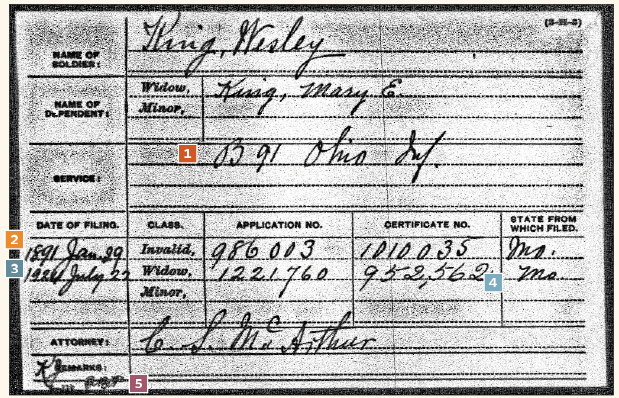

All Civil War Army pension application files at NARA are in the “Civil War and Later” series in Record Group 15. The vast majority of these pension files aren’t microfilmed or digitized, although a fraction are at Fold3. Two pension indexes can help you find your soldier’s file: The General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934, arranged alphabetically by veteran’s name, is on microfilm (T288) and online at FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com. The Organizational Index, arranged by state and military unit, is on microfilm (T289) and online at Fold3.

When searching these indexes, it’s helpful to know the soldier’s unit, state and widow’s name to ensure you’ve identified the right man. Both sets of cards indicate the filing date, application number and certificate number of the invalid and/or widows’ pension. Use the last number assigned to order the file from NARA. One exception: If your ancestor was still receiving benefits after about 1928, you’ll see an X or XC on the General Index card. While you should still check NARA first, this indicates the Veteran’s Administration may hold the file.

FamilySearch’s US Civil War Era Records web page is a good launching point for Union and Confederate Civil War research. Related Union records on FamilySearch.org include Veteran’s Administration Pension Payment Cards (1907-1933), Remarried Widows Index to Pension Applications (1887-1942) and Index to General Correspondence of the Pension Office (1889-1904).

In addition, a five-volume list of 1883 pension rolls is digitized on Ancestry.com and free via Google Books. If your ancestor served in the Navy, check the Navy Survivors’ Certificates and Navy Widows’ Certificates (from NARA microfilms M1469 and M1279, respectively) of approved naval pensions from 1861 to 1910. Both collections are online at Fold3 and in Ancestry.com’s “US Navy Pensions Index, 1861-1910” database.

Confederate soldiers

Following the Civil War, each southern state issued its own pension laws and retained its own records. NARA doesn’t hold Confederate pension files; you must get them from the state that issued them. Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia all have pension collections.

A Confederate soldier had to apply for a pension from the state where he was currently living. This wasn’t necessarily the state for which he served during the war. Like the federal government, most Southern states initially offered pensions only for death and disability. General service pensions came later, and many required applicants to prove financial need. Some Southern states have suffered record losses; for example, most South Carolina pensions issued before 1919 were lost in a fire.

NARA is still a good place to begin your search because of its online Confederate Pension Records guide. The guide gives contact information for each state agency, along with links to databases. Another helpful resource with links is the FamilySearch Wiki Confederate pension records article. FamilySearch has microfilmed all known Confederate pension records and digitized many.

Increasingly, more state indexes and records are appearing online. Ancestry.com has pension collections for every southern state except South Carolina. Find them by going to Ancestry.com’s online database catalog and entering Confederate pension in the Keyword search box.

Ordering and using a pension file Once you’ve identified your ancestor in a pension index, you’ll probably be eager to get a copy of the file. You can obtain copies from NARA in person, by mail or online using NATF Form 85. Find instructions and links in the Military Pension/Bounty Land Application section. Select the full or complete file (not the pension documents packet) for the right time period. Pre-Civil War files cost $55. Civil War and later files cost $80 for up to 100 pages; if the file is longer, they’ll tell you how to order the rest of it. You can opt to receive paper copies or a PDF file on CD/DVD. Allow up to 90 days to receive your order. To order a Confederate Civil War pension file, contact the appropriate state archive.

Once you receive a copy of a pension file, what do you do with your find? The pages of the file may not be in logical order, but first, carefully read through it just the way you receive it. It may reveal names, dates and relationships for your family history. Experts recommend transcribing the pages word for word to best absorb and correlate the information. For long files, you may have to selectively transcribe the pages that contain pertinent information.

After noting the original page order, you can rearrange the pages chronologically or sort them according to your needs. Keep a list of questions that come to mind as you read and think about the records. Can you find something in the file that suggests an answer? Where else might you look?

Common abbreviations you might find in files include:

• S.O.: Soldier’s original application for a pension

• S.C.: Soldier’s certificate number of approved pension

• W.O.: Widow’s original application

• W.C.: Widow’s certificate number

• B.L.: Bounty land warrant number

As you become familiar with pension records, you’ll probably find it helpful to learn more about military service, pension laws and types of associated records. A pension file may lead you to service records, unit histories, bounty land grants, payment vouchers, marriage or divorce records, cemeteries, the registers of soldiers’ or orphans’ homes, the special 1890 veterans’ census, lineage society records and more.

Your Revolutionary War, War of 1812 or Civil War ancestor likely put considerable time and effort into applying for a military pension. Fortunately, it’s easier than ever to get a copy of that pension record today. As some of the largest and most interesting sources that genealogists use, pension files have the potential to reveal key dates, places, names and events. Adding them to your research arsenal can open up a whole new frontier for discovering your ancestors.

Fast Facts

• Records begin: 1775, but few Revolutionary War pension files issued prior to 1814 survive

• Records end: Union Civil War pension files closed by 1928 are at the National Archives (NARA); files still open later may be held by the Veteran’s Administration

• Key details in pension records: soldier’s name, age, rank, unit name or number, date and place of enlistment, service term, residence and disability (if any); in widows’ files, also the maiden name, age, date of veteran’s death, date and place of marriage, names and ages of minor children; records also may include previous marriages, names of relatives, and birth dates and places.

• Where to find: most federal pensions are at NARA; Confederate Civil War pensions are at state archives where pensioner lived; Revolutionary War and some War of 1812 and Civil War Union pensions are on microfilm and digitized; indexes to other federal pensions are on microfilm and online

• How to order from NARA: use NATF Form 85

• Online availability: Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, Fold3, some state archive websites

• Search terms: Revolutionary War, War of 1812 or Civil War plus pension records; Union pensions; Confederate pensions plus the state name

• Associated records: compiled service records, payment vouchers and ledgers, unit histories, pension rolls, lineage society applications, soldiers’ home records, 1890 veterans’ census, bounty land grants

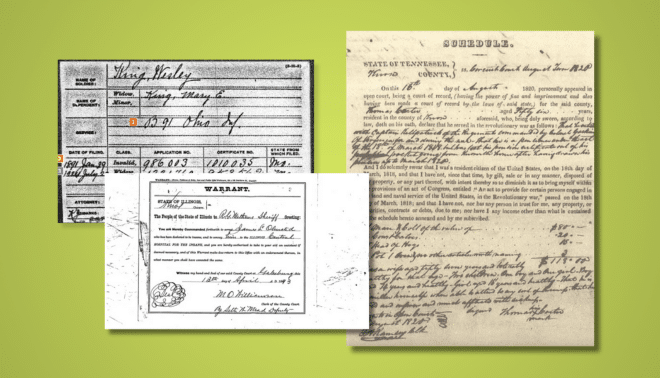

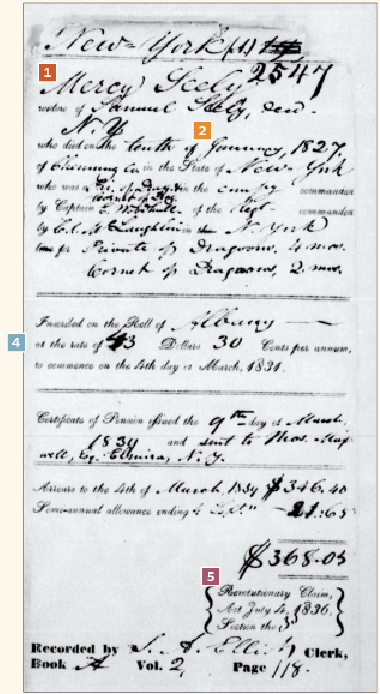

Record At A Glance: Revolutionary War Pension File

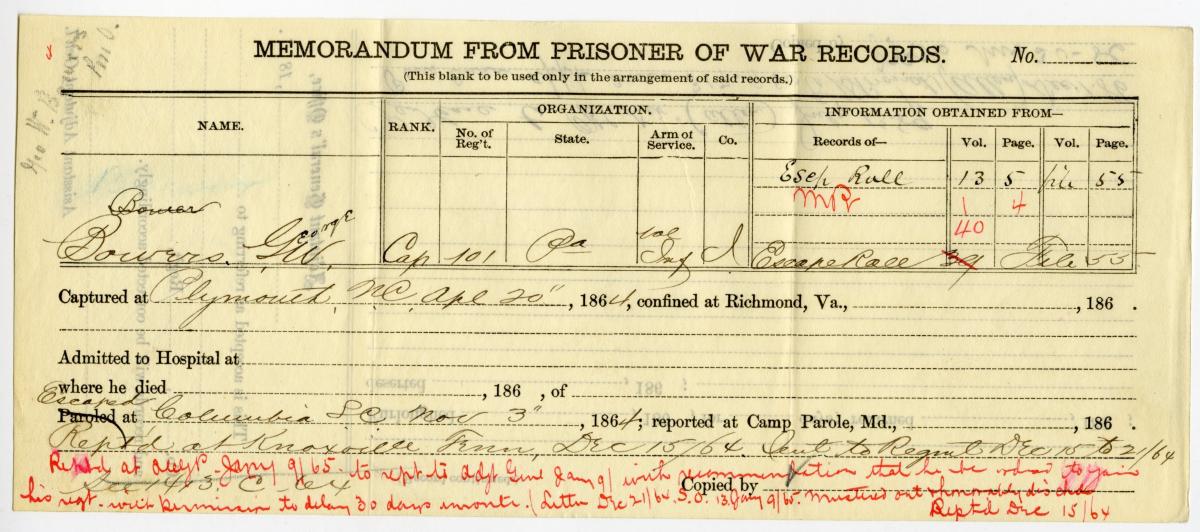

1. Mercy Seely, widow of Samuel Seely, received this pension for his service in New York. Like many veterans, Samuel died before an 1832 law made service pensions available.

1. Mercy Seely, widow of Samuel Seely, received this pension for his service in New York. Like many veterans, Samuel died before an 1832 law made service pensions available.Record At A Glance: Civil War Union Army Pension Index Card

Toolkit

Websites

• Ancestry.com: Pensions

•Confederate Pension Records guide

• Cyndi’s List: US Military Records

• FamilySearch Wiki: US Military Pension Records

• FamilySearch: US Military Records Collections

• Fold3

• Georgia Confederate Pension Applications

• HeritageQuest Online

•National Archives: Research Military Records

• National Society Daughters of the American Revolution

• National Society United States Daughters of 1812

• Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800

• Understanding Civil War Pensions

Publications and Resources

• Genealogical Resources of the Civil War Era by William Dollarhide (Family Roots Publishing Co.)

• Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States, 3rd Ed., by Anne Bruner Eales and Robert M. Kvasnicka (NARA)

• Index of Revolutionary War Pension Applications in the National Archives (National Genealogical Society)

• Index to Old Wars Pension Files, 1815-1926 by Virgil White (National Historical Publishing Co.)

• Index to War of 1812 Pension Files by Virgil White (National Historical Publishing Co.)

• Military Pension Laws, 1776-1858 by Christine Rose (CR Publications)

• Revolutionary War Pensions by Lloyd de Witt Bockstruck (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

•U.S. Military Records by James C. Neagles (Ancestry)

Put it Into Practice Quiz

2. Which resource typically contains more personal details for genealogy?

a. a compiled service record

b. a pension record

3. Where are most pension files issued by the federal government held, and how can you get a copy of one that’s not available online?

Exercise A: Go to Fold3’s main search page, click on War of 1812 and browse all War of 1812 titles. Select the free War of 1812 Pension Files collection. Enter the name Thomas Campbell in the search box and hit Go. When results appear, select the soldier from North Carolina (his file contains 74 pages). Click on View Larger.

1. What company did Thomas serve in?

2. What was Thomas’ wife’s maiden name? When and where did they marry?

3. What else does the card show Hannah received for Thomas’ service?

4. Write a citation for this record, using the source information that appears beside the image. (Browse through the pages to see the variety of documents the file contains.)

Exercise B: Choose an ancestor who served in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812 or Civil War who might have received a pension. Search for him in the databases on Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and Fold3 discussed in this article. If you find an index card, but the pension file itself is not online, determine the certificate number you’d use to order it.