Thanks to “American Idol,” “Survivor” and their reality-TV brethern, just about anyone can achieve instant fame. Of course, it hasn’t always been that way. Years ago, the path to stardom involved more than garnering millions of votes via cell phone or ingesting vile insects on a remote island.

Yes, show business has evolved (some might say devolved) considerably from the “classic” entertainment our forebears enjoyed—theater, vaudeville, radio, opera. What hasn’t changed is the important role entertainment has played in our culture. Ever since the ancient Greek tragedies, people have been performing for others’ amusement, and plenty have made a living at it. Did any of your relatives star in local theater productions, dance across Broadway or make ’em laugh under the carnival tent? Follow these six tips to bring your showbiz ancestors to center stage.

1. Research your ancestor’s talents

Performers paid their dues before hitting it big, so start locally to learn about your ancestors’ talents. Scour high school and college yearbooks for their pictures and activities they participated in. In Duquesne High School’s 1951 yearbook, for example, I discovered my uncle Nick was in the drama club — he’s even in the group photo. Check the senior class highlights, too: The same annual profiled a student named Louie as “tall, dark, and handsome … outstanding voice, which he used in the Mixed Octette … plays violin well.”

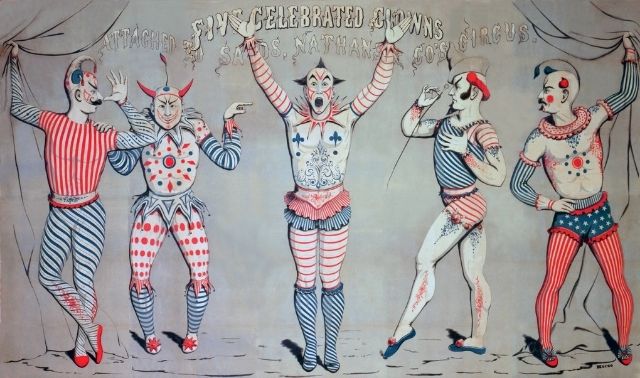

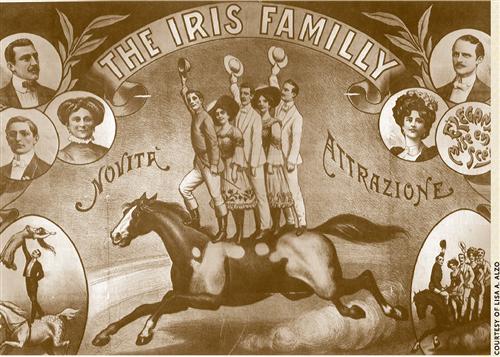

Also look for playbills, ticket stubs and other memorabilia tucked into yearbook pages — they may tip you off to a relative’s talents. While cleaning out my parents’ closets, I found an old Syria Temple Shrine Circus program from a performance in Pittsburgh. It detailed the acts, had photos of the performers and listed sponsors.

Other local sources might hint at an ancestor’s theatrical or musical endeavors: Town and local histories often spotlight residents” accomplishments. City directories — the precursors to modern telephone books — list people’s occupations; they also contain advertisements, which you can scan for local theaters and other venues.

Search Google to identify libraries, museums and historical societies in your ancestor’s area, which serve as storehouses for all of these sources. You’l find some city directories online at Ancestry.com and Fold3. For yearbooks and memorabilia, check flea markets, antiques shops, estate sales and eBay.

And don’t overlook family members. A friend of mine obtained a copy of a decades-old letter to his mother’s oldest sister, which describes the musical career of his ancestor Karl Haney: “He taught himself piano. He had perfect pitch and such a feeling for music. It had to be born in him. Later he traveled with a circus band one or two seasons, theater work and played with all the big bands, Sousa, New York Philharmonic, Pittsburgh Symphony … He also played in the Homestead and Braddock Library Bands when I was very young.” The letter continues with telling details—including names and places—my friend could use to uncover even more information about his ancestor.

2. Learn about old-time entertainment

Learning about old-time entertainment puts your ancestor’s role in context and focuses your research by providing additional leads. American Variety Stage, part of the Library of Congress’ American Memory Web site, is a treasure trove for vaudeville history: You’l find information about performers and theaters, sample playbills, sound recordings and other goodies. American Memory has several more entertainment-themed collections, including The New Deal Stage: Selections From the Federal Theatre Project.

For your Broadway-bound relatives, check the Internet Broadway Database, the official online archive of the “Great White Way.” If your ancestor had an unusual skill, you might find a website devoted to it (such as www.swordswallow.com) using Google or another search engine.

Some cultural groups had rich theatrical or musical traditions — for example, 200 traveling Yiddish theater companies were performing around the country between 1890 and 1940. Type the group plus keywords (such as yiddish vaudeville or african american theater) into the WorldCat metacatalog to identify heritage-focused social histories and locate them in nearby libraries.

You’l also want to chronicle your performer relative’s legacy in pictures. Besides American Memory, search DeadFred and Ancient Faces for photos of historic Hollywood and vaudeville. Old Postcards’ collection of more than 50,000 vintage cards includes images of historic theaters and performance venues; eBay is a great source for posters and other memorabilia.

You might even be able to track down a photograph of your ancestor or his troupe on the Web — for instance, the University of Washington Library has a collection of 19th-Century Actors Photographs. Try a Google search on terms such as historical actor photographs and vaudeville photos.

The University of Iowa Libraries’ special collections department has a terrific resource on East Coast vaudeville: the Keith/Albee Collection. Covering 1894 to 1935, it chronicles the expansion of the circuit, changes in leadership and vaudeville’s decline. Especially valuable to genealogists are the descriptions of both little-known performers and vaudeville stars. Because the collection contains fragile and oversized documents, the staff doesn’t fulfill research requests, however—you’d have to go there yourself or hire a local researcher.

Even familiar genealogy records websites are worth a try: Searching on show business at Fold3, I turned up a 1918 passport for circus performer Charles Sasse and a Lincoln Theater playbill.

3. Deconstruct stage names.

Celebrity pseudonyms aren’t a modern phenomenon—just as today’s actors often change their monikers to sound more “Hollywood” or mainstream, performers in olden days also adopted names as part of their on-stage personas. Hungarian-born magician Harry Houdini, for example, began life as Erich Weisz (later Ehrich Weiss). He took his stage name as an homage to a French magician he admired, Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin.

But how’s a genealogist to tell that Maxmillian the Magnificent is actually her ancestor Michael Maxwell? Several websites catalog stage-name conversions. You’ll find a list of vaudeville performers’ names at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/category:vaudeville_performers; click any name to view a bio that reveals the person’s original name. SideshowWorld links to some performers’ bios, as well as historical sideshow Web sites.

You also can try searching court records for official name-change documents. But many performers adopted their stage names informally—so ultimately, you might have to settle for circumstantial evidence, by looking in other records that might reference the old and new monikers.

4. Look for biographies.

Biographies are a great resource for tracking showbiz ancestors. Performers’ star status means they’re more likely than the average person to be profiled online or in a book. Start at sites such as Biography.com, which offers short bios of 25,000 famous folks, and Infoplease, with 30,000 entries. Search for famous females in Biographies of Notable Women.

Next, look for entertainer biographies in book form. Performing Arts Biography Master Index edited by Barbara McNeil and Miranda C. Herbert (Gale) catalogs 270,000 biographical sketches from 100 different performer directories. George B. Bryan’s Stage Lives: A Bibliography and Index to Theatrical Biographies in English (Greenwood Press,) covers 4,000 artists. Vaudeville, Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, 2 volumes, by Frank Cullen (Routledge Press) contains 1,000 biographies.

Other vaudeville resources include The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville by Anthony Slide (Greenwood Publishing Group), No Applause—Just Throw Money by Trav SD (Faber & Faber) and Women Vaudeville Stars: Eighty Biographical Profiles by Armond Fields (McFarland & Co.). Use WorldCat to locate libraries that have the books you want? if they’re not available nearby, ask your reference librarian if you can borrow them through interlibrary loan.

Be sure to look in general biographical compilations, too, such as the Who’s Who series (in libraries) and the American Genealogical Biographical Index, at large libraries and online at Ancestry.com.

5. Scan through newspapers.

Entertainment news was a big part of yesterday’s media, too (minus the celebrity rags and paparazzi), making newspapers an obvious source for researching your showbiz ancestor. Look in the society pages for marriages and special appearances, as well as advertisements announcing upcoming performances.

I found one such gem while browsing microfilm of the McKeesport, Pa., Daily News. In the Sept. 13, 1941, edition was the headline “Charles Wakefield Cadman, Composer of Fame, Once resided in Duquesne.” This profile—complete with a photo—talks about the musician’s localities as a former resident, and tells his year and place of birth, his sister’s name, and schools he attended.

Showbiz ancestors are almost certain to show up in the obituary pages, which will likely recount their performance careers. Houdini’s Nov. 1, 1926, New York Times obituary, for example, tells of the magician’s joining the circus at age 9, regaling European audiences with his tricks and confounding President Theodore Roosevelt. You can use resources such as Online Searchable Death Indexes & Records and Stage Deaths: A Biographical Guide to International Theatrical Obituaries, 1850-1990 compiled by George B. Bryan (Greenwood Press) to track down obits and death notices. (No burial info in the newspaper? Find A Grave‘s <www.findagrave.com> and Interment.net‘s user-submitted gravestone transcription databases could help you find your ancestor’s cemetery.)

Libraries often have historical newspapers on microfilm. Visit the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America directory to identify US newspapers published since 1690 and learn which libraries have them.

Old newspapers are increasingly being digitized and posted online in searchable form, too. Through libraries that subscribe to ProQuest Historical Newspapers, you can search happenings in entertainment hubs from the Big Apple to Hollywood: New York Times coverage goes back to 1851, the Los Angeles Times to 1881. Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank also have sizable collections. Search Google (try historical newspapers) or browse the links at Cyndi’s List to turn up smaller-scale sites that may hold hidden gems.

6. Turn to archive or museum records.

If your usual research protocols don’t produce results, you can try writing to an archive or museum affiliated with your ancestor’s showbiz profession to see if it has any records that could help you (see the resources section below for suggestions). Keep your requests brief, and include details such as your ancestor’s name, age, the time frame for his career (or years he performed for that company) and special physical characteristics or talents (juggler, clown, trapeze artist). Consult the organization’s website for specifics. With some, such as the Circus Historical Society you pay a fee to become a member, which gets you access to newsletters or other information.

To save time—and learn the group’s guidelines for research requests—consider calling or e-mailing first. Remember: Employees or volunteers affiliated with these archives and museums aren’t there to be your dedicated research assistant, and they’re often inundated with requests. So be courteous and concise when asking for information. You’ll also need to be patient-your request may not be answered immediately. If you haven’t received a response within six to eight weeks, follow up with a phone call, e-mail or brief second request. Or if you’re able to travel to the museum or archive (and the organization allows it), consider making a visit for on-site research.

Lucky for your ancestors, they didn’t have to win immunity idols or suffer Simon Cowell’s biting critiques to make their mark on entertainment history. Use your own talent for sleuthing to ensure they keep stealing the show.

Researching Circus-Performer Ancestors

Who doesn’t remember his or her first trip to the circus? The magical performances under the big top, scents of peanuts and popcorn, parade of animals, flying trapeze artists and, of course, the clowns. From the ancient circus day in Pompey’s Rome to today’s “Greatest Show on Earth,” the circus has entertained millions and provided livelihoods for countless men and women all over the world. If your ancestor jumped aboard a circus train or spent time in the carnival tent, use these tips to find out more.

Learn the big-top backstory.

The first American circuses began shortly after US independence, and circuses became a popular source of entertainment during the 1800s. At the beginning of the 20th century, more than 100 circuses were traveling around the country, performing for nearly 12,000 spectators at each stop. Get a crash course in circus history and lore at circushistory.org. You can learn P.T. Bamum’s genealogy at www.barnum.org and read how the Ringling Brothers got their start at www.ringling.com.

Jump in the resource ring.

You’ve discovered your forebear was a “fancy pants” or “roustabout” — but what does that mean? Check out The Circus Dictionary for definitions of 300-plus circus terms. Then search FamilySearch for the keyword circus to learn what records they may have. You can browse circus-related biographical sketches from 1733 to 1870 in the online version of T. Allston Brown’s History of the American Stage.

Perform ancestry acrobatics.

Just as high-wire acrobats reach out to support each other, so do genealogists. Reply to a query or post one about your circus ancestor on the Circus Historical Society’s message board or on related Facebook groups. Scour the Occupations, Circus and Theater sections of Ancestry.com’s message boards.

Researching Show Business Ancestors Resources

Websites

Books

The African American Theatre Directory, 1816-1960: A Comprehensive Guide to Early Black Theatre Organizations, Companies, Theatres, and Performing Groups by Bernard L Peterson (Greenwood Press)

American Sideshow: An Encyclopedia of History’s Most Wondrous and Curiously Strange Performers by Marc Hartzman (Tarcher)

Carny Folk by Francine Homberger (Citadel)

Finding Your Famous (and Infamous) Ancestors by Rhonda R. McClure (Betterway Books, out of print)

From Traveling Show to Vaudeville: Theatrical Spectacle in America, 1830-1910 edited by Robert M. Lewis (Johns Hopkins University Press)

A Geographical Index to Local Histories of the Theater in America by Clifford Eugene Hamar (Stanford University Department of Speech and Drama)

Opera on the Road: Traveling Opera Troupes in the United States, 1825-60 by Katherine K. Preston (University of Illinois Press)

Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical Theater by John Bush Jones (Brandeis University Press)

A Pictoral History of the American Theater 1860-1970 by Daniel Blum (Crown Publishing Group)

The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero by William Kalushand Larry Sloman (Atria)

Theatre in the United States, Vol. 1: 1750-1915 edited by Barry B. Witham (Cambridge University Press)

Two Hundred Years of the American Circus: From Aba-Daba to the Zoppe-Zavatta Troupe by Tom Ogden (Facts on File)

Vaudeville, Old & New: an Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America by Frank Cullen (Routledge Press)

Where Are They Buried? How Did They Die? Fitting Ends and Final Resting Places of the Famous, Infamous, and Noteworthy by Tod Benoit (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers)

Where the Bodies Are: Final Visits to the Rich, Famous, & Interesting by Patricia Brooks (Globe Pequot)

Wild, Weird, and Wonderful: The American Circus 1901-1927 by Mark Sloan and F.W. Glasier (Quantuck Lane Press)

Organizations

International Brotherhood of Magicians

International Clown Hall of Fame

Theatre Historical Society of America

A version of this article appeared in the January 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Updated: August 2021

Related Reads