Sensitive subjects were rarely mentioned Sat our house, but three were particularly taboo — money, my father’s being Jewish and sex. None of the three was ever articulated by any of us in the family; in fact, nothing difficult or personal was discussed among us. There was such an aversion to talking about money or our wealth that, ironically, there was, in some odd ways, a fairly spartan quality to our lives. We were not showered with conspicuous possessions, elaborate toys or clothes. At one point, when my sister Florence was 11, my mother wrote in her diary that she had gotten Flo very modest presents for her birthday — “books, pralines and other simple things.” Though Mother felt that she had been a bit mean, she also felt that “it is the best way to continue their chance for happiness to restrain the desire for possessions.”

Remarkably, the fact that we were half Jewish was never mentioned any more than money was discussed. I was totally — incredibly — unaware of anti-Semitism, let alone of my father’s being Jewish. I don’t think this was deliberate; I am sure my parents were not denying or hiding my father’s Jewishness from us, nor were they ashamed of it. But there was enough sensitivity so that it was never explained or taken pride in. Indeed, we had a pew in St. John’s Episcopal Church — the president’s church, on Lafayette Square — but mainly because the rector was a friend of the family. When I was about 10, all of us Meyer children were baptized at home to satisfy my devout Lutheran maternal grandmother, who thought that without such a precaution we were all headed for hell. But for the most part, religion was not part of our lives.

One of the few memories I have of any reference to my being Jewish is of an incident that took place when I was 10 or 11. At school, we were casting for reading aloud The Merchant of Venice, and one classmate suggested that I should be Shylock because I was Jewish. In the same way I had once innocently asked my mother whether we were millionaires — after someone at school accused my father of being one — I asked if I was Jewish and what that meant. She must have avoided the subject, because I don’t remember the answer. This confusion about religion was not limited to me: My sister Bis recalls that at lunch in our apartment in New York once, with guests present, she blurted out, “Say, who is this guy Jesus everyone is talking about?”

My identity as Jewish did not become an issue until I reached college and a discussion arose with a girl from Chicago who was leaving Vassar. She had been asked if she would see another acquaintance, a Jewish girl, also from Chicago. “Oh, no,” she replied, “you can’t have a Jew in your house in Chicago.” My best friend, Connie Dimock, later told me how horrified she was to have this said in front of me. Only then did I “get it” — and this was 1935, with Hitler already a factor in; the world.

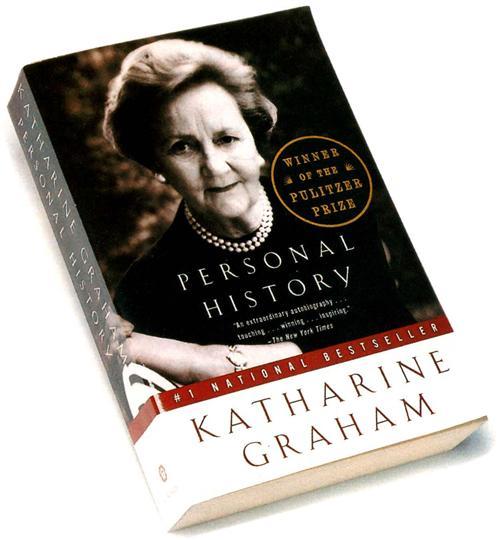

From Personal History by KATHARINE GRAHAM, copyright © 1997 by Katharine Graham. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House Inc.

From the October 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.