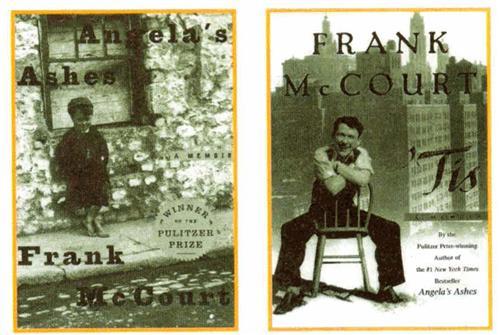

Frank McCourt would seem to have more than his share of the luck of the Irish. His memoir, Angela’s Ashes (Touchstone), shot onto the bestseller lists, sold more than 2.5 million copies, and won a Pulitzer Prize. The eagerly awaited sequel, ‘Tis (Scribner), became an instant bestseller when it was published this fall. Now there’s a new movie version of Angela’s Ashes, starring Emily Watson as mother Angela and Robert Carlisle as father Malachy (Young Frank is played by a progression of six Irish boys, cast from 6,000 who auditioned.)

Yet behind Angela’s Ashes is the painful true story of McCourt’s childhood in the slums of Limerick, Ireland. ‘Tis picks up the saga from his arrival in New York City at age 19 until, as a middle-aged man, he spread his mother Angela’s ashes. McCourt’s success is inextricably intertwined with his family history, and his story resonated with so many readers in part because it echoed that of their own immigrant ancestors.

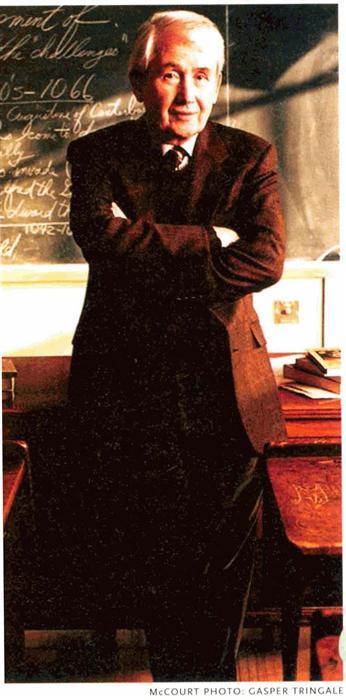

McCourt, 69, talked with Family Tree Magazine about his family history and his 30-year struggle to set it down on paper:

I learned storytelling at my mother’s knee, at my mother’s breast. It was the community, the lane, the slums. Everybody in Ireland was a storyteller. Books were so rare they were treated like gold. Writing was the joy of my childhood.

As a child I wrote on the back of brown paper bags under a street lamp in Limerick. I was always scribbling, always putting together stories. That’s how I earned the respect of the kids on the block. And when my fifth-grade teacher threatened to flunk me because I’d missed too many classes, the essay I wrote saved me. I learned early that language was power.

When you have nothing, you remember everything. In the Limerick slum — and yes, it was a slum, not a ghetto; no euphemism will work — there were no TVs, no computers, no videos. There was also no static. There was nothing between us and life. Everything was immediate and intense.

There were parts in the book that were hard to write: My mother’s humiliations, my father’s leavings, the sordidness of my going around from pub to pub looking for him, and then trying to get him to come home. Then there’s the time he took the pound my grandparents sent him and just went off and drank it. But it’s the process of writing that I enjoy. That’s why I was put here.

When I taught high school English and creative writing, I’d write two words on opposite sides of the chalkboard: “Fear” and “Freedom.” I’d tell the students that the first word, “Fear,” is something we all suffer from. But the second word, “Freedom,” we don’t all achieve. Angela’s Ashes was cathartic. It helped me to face my past, to achieve that freedom.

The best thing is to have done it. It had been gnawing at me for 30 years. If the book had sold its original 27,000 copies, that would have been enough for me. This success is like a Christmas tree with packages piled halfway up the tree. It’s almost too much to handle. What do I do with all these packages? There’s only one package that I care about. And that’s the one where I’m sitting at the table and writing the next book.