My grandmother baked cookies, but she didn’t believe in eating them fresh from the oven. She stored them in her cookie jar for a day or two before she would let me have any. “Wait till they come in order,” Granny would say. The crisp cookies softened in their ceramic cell — their snug humidor — acquiring more flavor, ripening both in texture and in my imagination.

“Coming in order” — my life is coming in order, as memories waft out of that cookie jar. But what is the recipe for those cookies? Who knows? My grandmother is dead, and her knowledge and memories are lost.

Like many Americans, I long to know the past. There’s a sense of loss in America today, a feeling of disconnectedness. We’re no longer quite sure who we are or how we got here. More and more of us are rummaging in the attic, trying to retrieve our history. We draw genealogical charts and hang old quilts on the wall. We seem to hope that if we can find out our family stories and trace our roots and save the old cookie jars and coal scuttles, we just might rescue ourselves and be made whole.

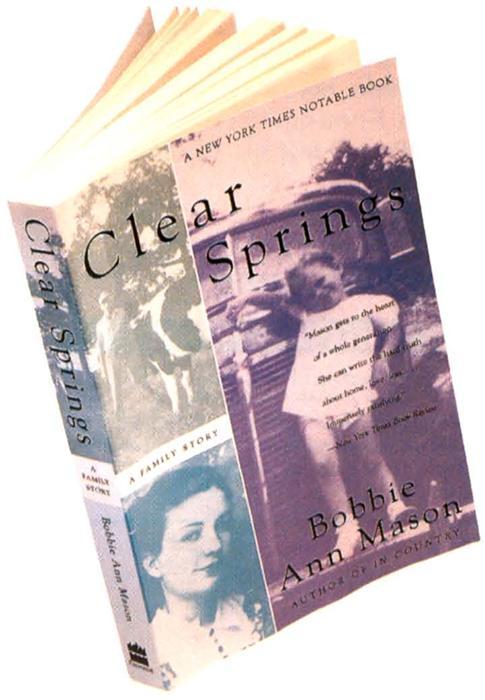

I grew up on a small family farm, the kind of place people like to idealize these days. They think the old-fashioned rustic life provided what they are now seeking — independence, stability, authenticity. And we did have those on the farm — along with mind-numbing, back-breaking labor and crippling social isolation. Sometimes I think I can remember the 19th century. When I was born in Kentucky, in 1940, farm ways had not changed much since pioneer times. No true cultural upheaval had hit Clear Springs, the rural community my family came from, since the Civil War. We seemed to live outside of time.

But World War II hurled us into the 20th century. All three generations of our extended family were challenged simultaneously by news from a fast-moving outside world. Suddenly it was possible for the newest generation of country people in our region to go to college, travel to Europe, and even choose a life off the farm. I didn’t want to spend my life canning beans and plucking chickens so, trundling my innocence before me like a shopping cart, I headed for New York — where else? — and got a job on a movie magazine. But I wasn’t a glamour-puss, I hated cocktail parties, and writing celebrity gossip soon palled. I wanted to be a real writer, which I thought meant I had to become a Greenwich Village bohemian.

Confused, unsure of my direction or purpose, I left the city for an upstate New York graduate school. Then the ’60s exploded. In one ear I heard the Beatles singing the magic of transcendence, and in the other I heard about my grandmother’s nervous breakdown, apparently caused by her worry over me — the innocent who had “gone off up North” to the evil big city. I teeter-tottered between two worlds. As I struggled to become sophisticated, my folks and their country culture were always present in the deepest part of my being. Yet I was estranged from them, just as I was a stranger there in the North. I was an exile in both places.

If my mother had had the chance, she might have busted out to the big city years before I dreamed of doing so. Many of the impulses I felt burned in her breast, too. But she remained caught in a household dominated by my cautious, worried, tight-stitched grandmother. To understand what happened to my mother and subsequently to me, I recently began to sort through the scraps of the past, looking for the patterns of our quilted-together lives.

From the October 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine