When my daughter and I both lived out of town and would come to visit my parents, we’d sleep in one of my brother’s rooms, which still contains his little-boy beds. My mom has enough space in her house for us to sleep separately, but we chose this room so we could spend the night together and trade magazines back and forth across the great twin bed divide.

A family tree hangs on the wall beside the bed my daughter slept in. It is a semi-elaborate work, drawn in gold and royal blue ink. It was presented to my grandmother, my Nana Amy, for her 80th birthday. It is actually more a chart than a tree, a chart consisting of squares filled in with names that diverge and connect with each other.

I’ve been looking at these names for years now: Adolph and Blanche, Rosa and Abraham, Morris and Anna, Frances and Allen, Eliza and Aaron, Henry and Molly, Amelia and Max. Amy and Alfred and Milfred and Ruby, Rosina, Rosa, Cora, Flora, and the poor baby girl who died at birth.

That’s what they’ve been. Names. Names in squares, not people. This is a geometric way to look at family, reminiscent, it has always seemed to me, of the way we used to diagram sentences in school. If Eliza and Aaron were the nouns, were Alfred and Amy the verbs? Was Uncle Mif the dangling participle?

This is why the stories are important. They put faces and actions and personalities to the names. They animate the squares.

My great-grandmother was Blanche. Blanche’s square connects with Adolph’s.

Blanche was literate and capable, according to my mother’s written history. “Not to be trifled with,” she writes. “Does that sound familiar?”

Yes, it sounds familiar. It describes my mother’s mother, my Nana Amy, Blanche’s eldest daughter, to a T

Blanche’s son, my Nana’s brother, remembers his mother as small, her features quite regular.

“She expressed her love for us in a quiet way and we regarded her highly for her assumption of both the father and mother role that became hers at a young age. Forty-six if my calculation is correct.”

Adolph would have been 50 on April 13, 1914. Blanche had planned a party for him. He died four days before his birthday. He was two years younger than I am now.

“I remember the day he died,” my great-uncle wrote in black ink on typing paper. “I was upstairs at home and I can remember my mother came in the house and said, ‘It seems like a dream.’”

Blanche’s friends were Stella, Tillie, Hattie, Jennie and Ida, Mink, Fanny and Eliza. Eliza became my great-grandmother, too. Her son, Alfred, married Amy, my Nana.

This I know from Nana’s sister, my Aunt Rosina, who we called RoRo.

“By the way,” RoRo wrote, “the ladies called each other ‘mrs.’ for a long time after becoming friends.”

A different era, a whole other time. I can see the ladies, Tillie and Stella and all the rest, arriving at a friend’s porch or entry hall, wearing gloves and hats and calling out for “Mrs.”

These are the things you don’t get from a chart or a family tree. The images, the history lessons, the character sketches, the customs. For these, you need the memories someone has had the benevolent foresight to write down.

My daughter named one of her kittens Ruby Rosina. She swears she wasn’t influenced by the family tree. I feel, though, some of its inhabitants must have whispered to her while we slept in those twin beds, having traded magazines and stayed up talking. Mother and daughter, connected forever, through Phyllis, through Amy, through Blanche.

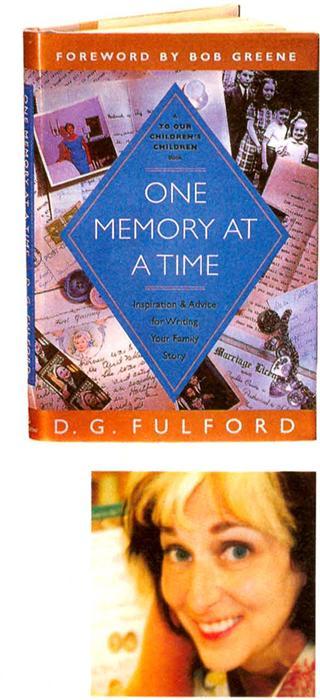

From the October 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine