Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

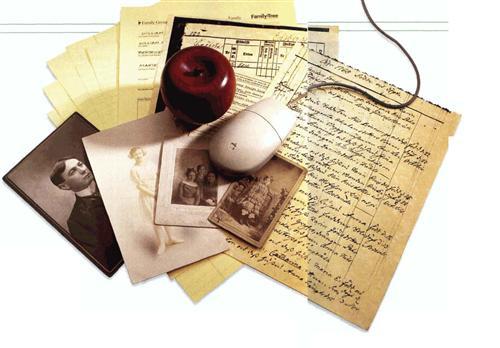

Genealogical research is a paper generator by nature. Visit any seasoned genealogist’s house, and you’ll discover piles of paper, bulging file cabinets and binders full of family group sheets, pedigree charts and old photographs. If you’re just starting your family tree, you might not have that much data yet — but you will soon, thanks to the Internet. Genealogy is now the second-most-popular subject on the Net (next to pornography), which means you can find millions of digitized records, compiled genealogies, photographs and other resources all at the click of a mouse. Chances are you’ll find a few distant cousins, too.

As you compile your family history, you can organize your research with one of the many genealogy software programs on the market. These programs enable you to type in your research just once, then print out attractive tables and charts you can show off to family and friends. They also let you publish your family tree online and swap data with other researchers using compatible software.

Genealogical research has never been easier. Of course, Internet genealogy is no substitute for flipping through original records, but it will give you a head start on your road to family discovery. And with the right software and organizational skills, you may be able to avoid those bulging file cabinets and piles of paper. Learn how to put your computer to work on your family tree with this roadmap to the information superhighway and genealogy software.

The library that never closes

When I work in a library, I’m forced to conclude my research at closing time. But online, 1 can research as long as my eyes stay open and my brain continues to function. Best of all, I can access records from around the world without leaving home. I can even wear my pajamas and bunny slippers while I surf the Net.

You can find all kinds of genealogy resources on the Internet, including census pages, vital records, tombstone transcriptions, land records, digitized newspapers and old photographs. Giant records repositories such as the National Archives and Records Administration <www.archives.gov> and the Family History Library in Salt Lake City <www.familysearch.org> are working to put their collections online, as are hundreds of state libraries and historical societies. And family historians have found the Internet an easy place to publish their research and connect with researchers with similar interests.

Just remember that you need to evaluate Web sites the same way you’d evaluate a book in a library. If a book has a bibliography and cites its sources, you can see where the author gathered her information and how she came to the conclusions in her book. Every Web site also should cite the sources of its data. If you can’t find source citations, contact the compiler; in most cases, you’ll find his or her e-mail address on the site.

With that in mind, here’s a look at the different types of genealogy Web sites. Each offers, a unique approach to research and can assist your quest for family knowledge.

? Directories: Perhaps the best-known genealogical directory is Cyndi’s List <www.cyndislist.com>, a catalog of more than 189,000 links organized into more than 150 categories. This is an excellent place to start your Internet research because it’ll give you an idea of what’s out there.

Keep in mind that the method by which any compiler organizes a directory may be different from the way you would have organized it. In other words, sometimes you won’t find a link under the subheading you think it should be under. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist; finding it will just require some creative thinking. If you’re looking for a Web site dealing with death records, for example, and you don’t find it under a “Death Records” subheading, perhaps it’s under a “Vital Records” subheading.

? Compiled family histories: Created by researchers of all skill levels, these are the most common genealogy Web sites. Content varies by site, but you’ll often find family trees, photos and links to related sites. An easy way to find compiled family histories is to type your surname (or your ancestor’s surname) into a general search engine such as Google <www.google.com> or a genealogy-specific search engine such as Ancestor Search <www.searchforancestors.com> or Family Tree Magazine‘s SuperSearch <www.familytreemagazine.com/search>.

Should you discover your family on such a site, jot down the information and the source. If the site doesn’t use source citations or the information contradicts your research, contact the compiler.

? Transcriptions or abstracts: Many genealogists participate in volunteer projects to transcribe or abstract records and make them available on the Internet. A transcribed record is a verbatim copy of the record that includes every word, misspelling and punctuation mark. With these records, you don’t have to wonder if the researcher left out important facts. Transcriptions take much longer to compile than abstracts, however, so they’re not as common.

When abstracting, the researcher records what she deems the pertinent facts for that type of record. For instance, in a land record, the pertinent facts include the names of the buyer and seller (grantor and grantee), the date of filing, the land description, the names of the witnesses and the release of dower, Remember that some of the people who abstract records are genealogy newcomers like you, and might not know which information they should include in an abstract. So when you visit their Web sites, you may discover that they left out an important detail. such as the release of dower. This is an important lesson about researching on the Internet: Never assume that compiled pages are complete. Always make note of questions, and try to answer them as you research.

? Searchable databases: Genealogists thrive on databases. One of the first databases available was the International Genealogical Index (IGI), which is searchable through the Family History Library’s FamilySearch Web site. The IGI lists the dates and places of birth, baptism, marriage and other events for I billion people who lived between the early 1500s and the early 1900s. The IGI is far from complete, but if you’re fortunate enough to find your ancestor in this index, you’ll have an idea of when and where he or she lived. The FamilySearch site now offers a number of additional searchable databases, as well.

You’ll need to find out who compiled the information in a given database in order to determine its validity. The IGI, for example, includes two types of research; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) patron submissions and extraction entries. The patron submissions, which come from information gathered by Latter-day Saints as they complete their family trees, may cite sources such as “family knowledge,” whereas the extraction entries have been carefully pulled from original records. When working with the IGI or any other database, look carefully at each entry for the source of the data. (Look for the batch number in IGI entries.)

Even entries extracted from original records may contain errors, though. If the database holds scanned images of records, errors couldn’t have crept in during digitization. While the original book may have had errors, at least neither human nor machine has compounded them. But even with the most stringent of verification practices, mistakes will sneak in when records are being digitized by hand. Therefore, you need to keep two things in mind when working with such databases. First, remember to verify the information against original sources whenever possible. Second, do not give up on a source just because you can’t find your ancestor in an online index. Perhaps the name wasn’t abstracted correctly, so your search won’t reveal the entry under the spelling or spellings you know. For example, the surname Hererndeen was included in one census index as Hundun. Until 1 found that, I had not thought of Hundun as an alternative spelling for Herendeen. I’ve since added it to my list of variant spellings, even though I haven’t seen it again.

? Discussion areas: We’re all guilty of hit-and-run research: We do a search on a search engine, click a link in the search results, read through the site, then move on. We forget that a person is behind that Web site — a family historian willing to share her research. Most genealogists are eager to connect with others to swap data, and to do so, they often utilize online bulletin boards and mailing lists.

The easiest way to comprehend an online bulletin board is to think of a physical bulletin board, such as one you might see in a college dorm or at the local library. These exist for many subjects, so you’ll need to search for one that fits your interests. A few to start with are GenForum <genforum.genealogy.com>, Ancestry Message Boards <boards.ancestry.com> and HeritageQuest Query Center <www2.heritagequest.com/eventcenter/qcenter.htm>, You might need to visit a message board frequently to view responses to your postings. Others offer e-mail notification when someone has responded.

Like bulletin boards, mailing lists cover numerous subjects — surnames, ethnicities, localities — and they come in two varieties. The first is the list mode, in which each message sent to the mailing list will come to you as a single e-mail message. It may be difficult to differentiate these messages from your regular e-mails. The second format is digest mode. This method sends you a couple of e-mail messages a day, depending on how busy the mailing list is. Each e-mail message contains a table of contents, followed by messages from subscribers. You’ll find genealogy-related mailing lists at Roots Web <lists.rootsweb.com> and Cyndi’s List <www.cyndislist.com/mailing.htm>.

? Commercial sites: To access the wonderful information commercial sites have squared away, you’ll have to pay for a subscription. These sites may let you run a complimentary search to see if your ancestor’s name appears, but seeing the actual information requires putting your money where your mouse is.

What draws researchers to commercial sites such as Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > and Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com> — which are owned by the same parent company — is the ability to access international birth, marriage and death records; census images; old newspaper pages; and more from one site. Essentially, they provide one-stop shopping from your computer. And, like everything else on the Internet, they’re always open.

But are these sites worth the money? That all depends on what each has to offer. If a site provides a clue that will help you break through a brick wall in your research, it’s definitely worth it. But if the bulk of the current resources exclude the localities where your ancestors lived, or if you can find the same information for free elsewhere, a subscription probably isn’t worth the money.

Getting with the programs

Before computers, family historians spent more time committing family histories to paper than they did researching. For each person on a pedigree chart, we had to write that relative’s information on three separate sheets of paper: the pedigree chart itself, the family group sheet where the ancestor’s listed as the spouse and the family group sheet where the ancestor’s listed as the child. Each paper included the same information about the person: name; spouse’s name; and dates and places of birth, marriage, death and burial. Now, if all your ancestors were named John Smith and they were born, married and died in the same town, this wouldn’t seem like such a horrendous process. I suspect few people are that lucky.

With genealogy software, however, you can enter a person’s information just once and reuse it to generate family charts.

No more writer’s cramp, and your files will be much more organized.

So how do you choose the right software program? First, find out if the program will let you record more life events than just births and deaths. Even if you don’t think recording the date of a bar mitzvah or first communion is important, the people you share your family tree with might find this information interesting. Recording additional life events also may help you track your hard-to-find ancestors and isolate those with common names.

While I consider myself pretty proficient at the keyboard, I’m more apt to make mistakes when I’m dealing with a lot of numbers and dates. As a result, I sometimes end up with a person dying before she was born. Luckily, many programs can be set up to warn you about such discrepancies.

Another great software feature is the ability to keep track of familial relationships. You are responsible for entering each person’s information correctly, but you can tell the program to create and print out a pedigree chart for a given line. If you were to create such a chart by hand, it would take some time to compile the proper families, going back the necessary number of generations and then listing them in the proper order and with the proper method. Your computer can prepare a chart in a matter of minutes. And no number of generations seems to be too much for a computer to handle.

Many programs also let you calculate how two people in a database are related. Instead of having to plot out the information yourself, you’ll get an answer quickly.

Sharing your work

While genealogists may prefer to work with pedigree charts and family group sheets, especially during the research phase, narrative-style reports will probably have greater appeal for our family members. Fortunately, the latest batch of software offers a vast array of pictorial and narrative-style reports that will appeal to nongenealogists. Take these reports to the next family gathering, and your relatives will find the organization and photos intriguing. Suddenly, the people who swore up and down that they didn’t know anything about the family will supply you with more information than you could hope to remember.

With the advances in genealogy software, you can publish your narrative report not only on paper, but also on the Internet. And you don’t need to be a computer whiz to do so. Your genealogy software will take care of much of the organization and structural work for you.

But before you publish on the Web, you need to understand GEDCOMs. GEDCOM stands for Genealogical Data COMmunication, and it’s the universal family tree file format compatible with most genealogy software. (In fact, you should be sure any program you buy is GEDCOM compatible.) It makes sharing data with other researchers possible. Basically, GEDCOM takes all the facts in your database and breaks them down into single pieces of information. These bits of data are identified with tags so that the program reading the file knows where to put each line of information — thus keeping all the family units together and all the events for each individual together. As a genealogy program reads the GEDCOM file (always given a .GED extension), it knows what to do with the names, dates, places, events, repositories and sources, and how to keep them linked as you go from one software program to another.

You can send your GEDCOM files to family members or to the Family History Library for sharing in the Ancestral File and Pedigree Resource File databases. Or use a GEDCOM-to-HTML converter such as GedHTree (<www.gedhtree.com/gedhtree.html>; PC, $20) or Ged2WWW (<www.lesandchris.com/ged2www>; PC or Mac, free) to put your pedigree online yourself — without having to learn programming code. To see examples of sites created with converters, visit <www.gedhtree.com/welkmayn/ghtindex.htm> and <www.lesandchris.com/genealogy/database>.

The only way is up

While genealogists look to the past for clues to their ancestors, they look to the future for the tools to time travel. Even those who grew up without computers have grabbed the beast by the horns and tried to master at least the basics, so they can come along for the ride. And what a ride it has been — and continues to be. Genealogy is more popular than ever, and technology has made research easier than ever. While seasoned genealogists like me were thrilled to have access to microfilmed census records, these records are now being made available online. And organizations are going even one step further: They’re enhancing those hard-to-read pages. This could mean a chance to find one of your lost families on a page that once was unreadable. The computer truly has become a wonderful vehicle for researching, organizing and sharing our family histories.

Excerpted from The Genealogist’s Computer Companion by Rhonda McClure (Betterway Books).

From Family Tree Magazine‘s November 2003 Trace Your Family History.