Sharon Diluvio always knew her grandfather as a hardened West Virginia coal miner. But his well-formed, richly curved script revealed an inner artistic bent. That confirmed her mother’s memories of a keenly observant father who loved nature and knew the name of every bird and tree. But maybe you have no memories of your ancestors — just the documents they wrote on.

Sharon Diluvio always knew her grandfather as a hardened West Virginia coal miner. But his well-formed, richly curved script revealed an inner artistic bent. That confirmed her mother’s memories of a keenly observant father who loved nature and knew the name of every bird and tree. But maybe you have no memories of your ancestors — just the documents they wrote on.

According to genealogical graphologists (handwriting analysts), your long-ago relatives actually wrote all about themselves on deeds, certificates, letters and other papers. Was your great-aunt Sarah demure or daring? Did your Colonial ancestor have an inquiring mind? They can tell you — not by what they wrote, but how they wrote it.

Graphology is no parlor trick, but a branch of psychology that’s performed by certified practitioners with years of training. The FBI uses graphology to enter the minds of its most wanted. Employers use it to select promising new hires. Historians use it to analyze the letters of famous people, from Winston Churchill to Marilyn Monroe. You can use it, too, to make some basic observations about your ancestors.

You probably already have the writing samples you need. Examples of ancestral handwriting abound in letters, diaries, store ledgers, the family Bible (even though entries may be short), deeds, court records, marriage certificates and naturalization papers (just make certain the writing isn’t the clerk’s!). Also gather old canceled checks (they carry signatures), Grandma’s recipe cards and photos with notes on the backs. Don’t read too much into any one sample — what if Great-granddad was angry when he penned that note? And like you, your ancestors changed over time. It shows in their writing: Three letters from your great-great-grandmother might introduce you to a hopeful bride, a loving mother and a revered matriarch.

Copy write

Remember learning to write by copying letters from the blackboard? By contrast, your forebears may have practiced from books of Spencerian and other now-antique handwriting styles. Graphologists such as Andrew Hunt, who specializes in genealogical work (see his Web site at <www.quantumenterprises.co.uk/handwriting>), pay special attention to these copybooks. Hunt says that compared to us, “previous generations were far more rule-oriented. They stayed much closer to their copybooks, meaning that large variations would suggest real independence.”

The writing styles in copybooks also vary by nationality. For example, your Hamburg kin’s knifelike strokes would normally indicate aggression, except that old German copybooks taught this very angular writing. Old Italian script looks curving and tall. What style of writing did your ancestors learn? You can view antique copybooks from around the world at <www.handwriting.org/main/hwacopyb.html>.

Hedy Bookin-Weiner, a member of the American Board of Forensic Handwriting Analysis, once examined the letters of an Englishman who left his homeland for the high-stakes gamble of the California Gold Rush. His writing was different from the examples in the Victorian copybook he would have studied. “This man’s handwriting showed extreme individuality,” Bookin-Weiner recalls, “a trait hardly tolerated in 19th-century Britain, but a key for success in the freewheeling American West.”

Writing instruments have changed, too. That explains the “thicks and thins” left by stick pens, used during the early 1800s, and fountain pens, which succeeded them around 1880. DiLuvio, a certified graphologist (see <www.4GenealogyNuts.com>), observes that your Colonial-era ancestor’s frequent smears don’t evidence confusion (the modern meaning). Rather, they’re the effects of rag paper and gall ink. Likewise, tiny writing from those days may merely reflect an attempt to save paper.

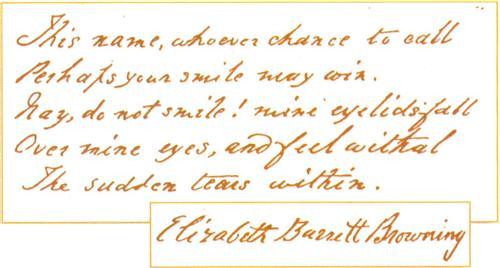

The high crossbars on poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ts reveal her lofty goals. Their placement to the right of the ts’ stems could mean she had a quick temper.

Metaphorically speaking

The first key to graphology is metaphor. In general, vigorous handwriting suggests a vigorous writer. Widely spaced words can mark emotional distance. Careful people write carefully, neatly dotting is and crossing ts. A business-minded kin’s entrepreneurial drive still lives in his firm, angular script. By contrast, your seventh cousin Horatio was probably impulsive. His words crash abruptly against the right margin — he doesn’t think ahead!

To understand how this works, try a simple exercise: First select an example of an ancestor’s handwriting and study it to get a general impression. Now describe how the writing looks to you: quick, forceful, systematic, detailed, enthusiastic. In basic terms, you may have just described your ancestor. Try the same exercise again, but this time turn the paper upside down — this will help you see the writing as patterns on the page, rather than focusing on what the words say.

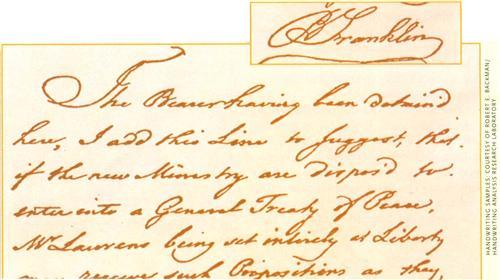

Tall upper loops in Benjamin Franklin’s writing indicate his interest in intellectual pursuits. Large capital letters show self-confidence, even conceit.

Different strokes

Next, look at the size of the individual letters. Larger writing indicates an extrovert, while smaller writing comes from quiet, introspective thinkers. The deep lower loops (common among “restless” folk) in your Wild West patriarch’s gs and ys help you envision the traveling man who spent his life in a saddle. How do your ancestor’s letters slant? In general, script that leans to the right suggests emotion, while “vertical writers” often are more formal. Words that lean backward may hold back information — literally. (Contrary to popular belief, the majority of left-handers normally don’t tilt their letters backward.) Also observe how the lines of writing rise or fall as they cross the page. In general, people whose script tilts upward are positive thinkers; lines that decline suggest a more somber manner.

Under pressure

Another key handwriting trait is how the writer applies pressure to the page. Your boisterous uncle Fred’s heavy pressure betrays his forceful, driving personality. Lighter lines are associated with a more gentle manner. How can you tell the amount of pressure the writer used? If you run your fingers carefully across the back of an old document, the pressure marks may still be there for you to find. (Such marks also permanently record where your ancestor first placed his pen tip, emphasized a point and paused to gather his thoughts as he wrote.) On a copied document, pay attention to how dark your ancestor’s writing appears, especially compared to someone else’s writing on the same document.

Sign here

Graphologists find that we sometimes express our feelings toward others by the way we write their names — or our own. Your Civil War ancestor loved his fiancee; see how he signifies her importance by writing her name slightly larger than the words around it. Your great-aunt Tessie, on the other hand, may have endured an unhappy marriage. The long crossbars on the ts in her signature cross out her last name!

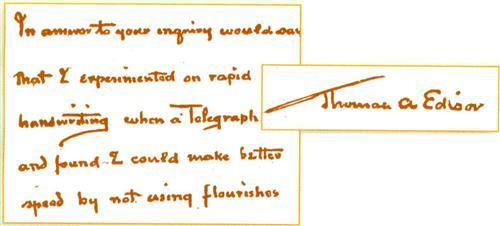

The wide spacing in Thomas Edison’s writing indicates a desire for social distance. Heavy pressure shows drive and determination.

The write approach

Graphologists also consider margin formation, how letters are joined (called garlanding) and a host of other handwriting characteristics. What can these reveal about your kin? You can find out by logging on to <www.quantumenterprises.co.uk> and <www.writinganalysis.com>. Both Web sites offer free, interactive handwriting analyses, complete with basic graphology reports. (For practice, try a sample of your own writing.) To see the same rules applied to the handwriting of historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln, visit <www.apogeegraphology.com/famouspeople6.html>.

To find a professional graphologist who can thoroughly analyze your ancestor’s writing, contact the associations listed in the Toolkit. Ask a pro about her certification and especially her experience with antique documents. The analyst also should request information about the writer’s age, birth date, country of origin and any health conditions that might affect his writing. Original documents reveal the most detailed evidence (especially those telltale pressure marks), but most graphologists will work from good photocopies. Some accept e-mailed scans. Substantive samples (say, 10 lines) are best; ideally, send several specimens.

You knew those old letters were precious. Now you know your ancestor’s writings have much more to tell you — maybe even a surprise or two.

From baptismal records to an old driver’s license, signatures often are the most accessible samples of ancestral handwriting. Although a stand-alone name is less revealing than a well-penned page, your kin’s signature still can provide a remarkable portrait.

That’s because graphologists find that, while your handwriting reveals your inner self, your signature presents your public image — the way you wish to be seen by the world. Thus, large capital letters say, “See me as important.” But overly large characters (see Richard Nixon’s signature at <iwhome.com/spectrum/presidnt.htrn>) can mark dangerous pride. An underscoring line — often seen in actors — can signify self-confidence. Neat, clear signatures speak to candor, while a disguised scrawl (when not written in haste) may reflect a guarded manner.

If you have a signed letter, you can compare the signature to the body of the letter. For example, rows of tiny script followed by a florid signature suggest that your third cousin was a shy thinker who showed a more forceful side to the world. Even the position on the page can be telling: A centered signature puts the writer at center stage — the choice of the outgoing.

Toolkit

Web Sites

• Analyzing Your Ancestor’s Handwriting

<www.ancestry.com/library/view/columns/george/31.asp>

• Cyndi’s List — Handwriting & Script

<www.cyndislist.com/handwrit.htm>

• FineLine Graphology

• Graphology Information Centre

<home.wmin.ac.uk/marketingresearch/graphinfo.htm>

• Handwriting Analysis: A Case Study

<www.ancestry.com/library/view/ancmag/764.asp>

Books

• The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Handwriting Analysis by Sheila R. Lowe (Alpha Books)

• Handwriting Analysis: A Complete Self-Teaching Guide by P. Scott Hollander (Llewelyn, out of print)

• Handwriting Analysis: Putting It to Work for You by Andrea McNichol (McGraw Hill/Contemporary Books)

• The Little Giant Encyclopedia of Handwriting Analysis edited by the Diagram Group (Sterling Publishing Co., out of print)

Organizations

• American Handwriting Analysis Foundation

Box 6201, San Jose, CA 95150, (800) 826-7774, <www.handwritingfoundation.org>

• Handwriting Analysis Research Library

Robert Backman, Curator, 91 Washington St., Greenfield, MA 01301, (413) 774-4667

• International Graphoanalysis Society