Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

More than 3 million Americans report having Scots-Irish ancestry. But who are the Scots-Irish? Are they Irish? Scottish? Irish and Scottish? Or are they something else entirely? Here’s a history of the Ulster Scots, plus how you can find your Scots-Irish ancestors.

Are Scots-Irish Scottish or Irish?

Simply put: The Scots-Irish are ethnic Scottish people who, in the 16th and 17th centuries, answered the call of leases for land in the northern counties of Ireland, known as Ulster, before immigrating en masse to America in the 18th century.

Since the Colonial period, the Scots-Irish have been one of America’s most interesting ethnic groups. Their distinct—some might even say stubborn—sense of independence has hurled them to and beyond the US frontier.

ADVERTISEMENT

That independence is present even in the group’s name. While Americans have often called them “Scots-Irish,” these fervent Protestants began adopting the term “Ulster Scots” in the mid-1800s to separate themselves from the generally Roman Catholic Irish immigrants arriving on American shores in droves. (For those not using the term Ulster Scots today, Scots-Irish has generally supplanted the use of “Scotch-Irish” in America.)

Their two-step immigration process (first to Ulster and then to America, often separated by a century or two) complicates Scots-Irish research. Record loss is another factor—assuming records were kept in the first place. But despite these difficulties, you can find a bagpipeful of records, documents and methodologies to track down the ancestry of these wandering, pioneering Ulster Scotsmen.

Why Did Scots Live in Northern Ireland?: Scots-Irish, Religion and Politics

Ethnic Scots ultimately lived in northern Ireland because of England’s historical desire to dominate Ireland. As early as the 12th century, English kings had made attempts to interfere with areas of Ireland.

ADVERTISEMENT

Fast-forward to the 1500s, when England’s Tudor Dynasty (notably King Henry VIII and his daughter Queen Elizabeth I) made it the Crown’s mission to bring Ireland under its control. Tensions were political as well as religious: After the Protestant Reformation, England became a Protestant country, while Ireland remained Catholic (and loyal to the pope).

The Anglo-Irish relationship became even more complex when the Scottish King James VI became King James I of England in 1603. Scotland also embraced the Reformation and became Protestant, albeit through its own Presbyterian Church of Scotland (rather than the Anglican Church of England).

And, given that parts of Ireland (especially in the northern area known as Ulster) were depopulated after earlier wars, James I came up with a plan: Take land from (Catholic) Irish nobles and give it to some of his (Protestant) cronies, who then would invite tenant settlers called “undertakers” from the lowlands of Scotland—just 20 miles away across the North Channel of the Irish Sea.

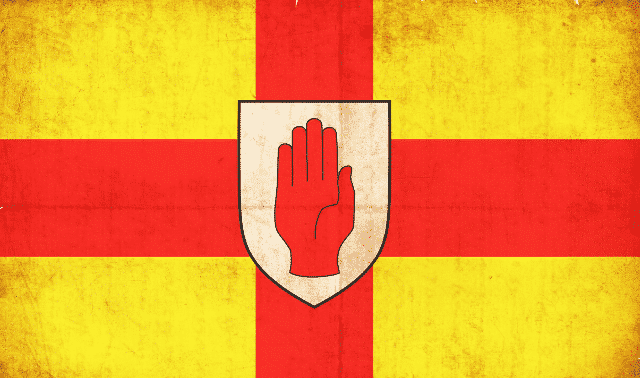

The Counties of Ulster

The land allotments appealed to these Scottish Lowlanders for a few reasons: Their own land on the border of England and Scotland had been cursed by war for seven centuries. And a change in land tenure rules had dispossessed many from their traditional lands. Some English from the England-Scotland border area also chose to settle in Ulster.

This “plantation” of Ulster began in 1609 and attracted thousands of settlers over the next couple centuries. It contained nine historical Irish counties:

- Antrim

- Armagh

- Cavan

- Donegal

- Down

- Fermanagh

- Londonderry

- Monaghan

- Tyrone

For a century, the Scottish colony in Ulster survived various rebellions; the remaining native Irish in the area did not take kindly to the “interlopers.” Each of these conflicts had the effect of attracting more Scots to Ireland. For example, in the 1650s a Scottish Covenanter army was sent to protect the colony, and many soldiers stayed after the war ended. Famine in Scotland in the 1690s also led many to Ulster.

Why Did the Scots-Irish Come to America?

Two major factors precipitated mass migration from Ulster to the American colonies in the 1710s. First, landlords sought large increases to renew the 20-year leases of many 1690s emigrants, leading to a “rack rent” crisis among Ulster Scots. Thousands were evicted from their lands. Second, the Presbyterians in Ulster were almost as politically disadvantaged as the Irish Catholics. Under British rule, only people who belonged to the Church of Ireland, the branch of the Anglican Church on the Emerald Isle, had the potential for political rights.

When added to occasional droughts in Ulster, these factors turned a trickle of Scots-Irish emigration into an open tap: Some 250,000 are thought to have come between 1717 and the beginning of the American Revolution. More than a million Scots-Irish would come to America in the 19th century.

After the first wave from 1717 to 1718, the Colonial era saw four more such upticks. The swells in the late 1710s and from 1725 to 1729 centered upon Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, the largest city and most important port in the Colonies, was the destination of the overwhelming majority of Scots-Irish. Many became the first pioneers of central Pennsylvania, which bears a host of names reminiscent of Ulster and Scotland, such as Carlisle, Cumberland, Rapho, Donegal, Derry and Londonderry. Scots-Irish generally planted settlements seven to 10 miles apart because that was about how far a family could ride to church for Sunday services.

As early as the 1740s, when the next great wave occurred, a number of Scots-Irish went into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and even into the Carolinas, where they pushed the envelope of settlement into and across the Appalachian Mountains. A limited number also came to New England. The final high tides of immigration occurred from 1754 to 1755 and 1771 to 1775.

The new American frontier allowed the Scots-Irish to realize their quest for land ownership. “There was a personal, passionate desire to own land permanently,” says Peter Seibert, a Scots-Irish expert and former president of the Heritage Center of Lancaster County, Pa. “They viewed land as the only true wealth.”

The Scots-Irish also sought independence and desired to stay at or beyond the limits of the authorities. Indeed, an oft-repeated axiom was that no Scots-Irish family felt comfortable until it had moved at least twice. But when these folks did find places where they would be left alone they became fiercely territorial, defending their homesteads and becoming known as hillbillies and rednecks by people who considered themselves more genteel.

Finding Scots-Irish Records in the United States

There’s a joke about searching for records of the Scots-Irish in 18th-century America: “They came, they left—and left no records.” While that’s an exaggeration, this group left less of a paper trail than other immigrant groups who arrived in the 1700s. Seibert notes that 19th-century Scots-Irish often gave children the mother’s maiden name as a middle name to tie themselves more firmly to clan and family. A good strategy can be to use “whole family genealogy”: tracing siblings of ancestors (this is also called “cluster genealogy”).

While you might be lucky enough to find a Scots-Irish immigrant’s origin on a tombstone or family record, in many cases the limited number of early documents won’t provide this information. But if you’re able to follow the immigrant’s descendants to where they ended up in the mid-19th century, a county history or newspaper obituary might well give the family’s Ulster county or village of origin. Therefore, you might need to trace several generations forward in time from your Scots-Irish immigrant—in a family line that is collateral to yours—to find information. Following are the records you’ll look for:

Passenger lists

The records dearth started when the Scots-Irish got off their ships in Philadelphia or other ports. Ports didn’t begin issuing comprehensive passenger arrival records until 1820. Philadelphia has lists for “foreigners” in the Colonial period, but because inhabitants of the British Isles—including the Scots-Irish—were subject to the King of England, they weren’t considered foreigners. For the same reason, you won’t find naturalizations of Scots-Irish before the American Revolution.

Some passenger listings show up in newspaper reports and in repositories (the Historical Society of Pennsylvania has a few, for example). For the 19th century, you can check standard sources of passenger lists such as National Archives and Records Administration microfilm, Ancestry.com’s paid-access immigration collection, the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild and Ellis Island.

Church records

Most Scots-Irish arrived in America as Presbyterians. They were considered “dissenters” in Ulster and thus did not carry with them a tradition of formal record-keeping. Records of baptism, marriage and burial were considered the personal property of the clerk of session (typically a congregational member who was in charge of keeping minutes at meetings and making annual reports for his local church). As a result, most Scots-Irish church records have been lost to history.

There are minutes of the church units called presbyteries from the 1700s, which yield some names. Surviving records can be found at the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania State Archives, historical societies of the congregation’s local area, and, of course, the local congregations themselves. “I’ve even found Presbyterian Church record books from the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania on eBay,” Seibert says.

Various schisms among Presbyterians aggravate this records situation. A split in the church from 1741 to 1758 centered on pastoral credentials (called the Old Side-New Side controversy), and 1837 saw a split over church governance and theology (known as Old School vs. New School). Geographic fractures occurred around the Civil War and the issue of slavery. In the past century and a half, most Presbyterian groups have reunified. That means you may find congregations of different denominational names, such as Reformed Presbyterian, United Presbyterian and Orthodox Presbyterian. On the positive side, more congregations in the 19th century kept records that survived. In the turmoil of the schisms, however, some Scots-Irish joined Baptist and Methodist churches, so check records from those groups as well.

Land records

Because Scots-Irish placed a high importance on land ownership, a wealth of information is available in land records (check with the county courthouse office in charge of deeds) as well as documents about land disputes (consult the county office in charge of civil court actions), which were often between family members.

And while it’s true that the early Scots-Irish knack for moving beyond authority—in this case, county boundaries—can stymie research, deeds eventually would be recorded. You may have to check deed indexes far beyond the time period in which an ancestor lived in an area, or even find later deeds to the property in question to uncover references to unrecorded transactions.

Finding Ulster Genealogy Records

Until 1922, the entire island of Ireland was one political unit; after that point, Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom and the rest of the island became independent. As a consequence, some government records before 1922 will be in Irish repositories and not in Northern Ireland.

As such, Scots-Irish research is affected by the destruction of the Public Record Office in Dublin during the Irish Civil War. Among the records lost were Ireland’s census returns from 1821 to 1851, registers from more than a thousand Church of Ireland parishes, and virtually all the wills probated before 1900 (though not the will indexes, called “calendars,” as noted below).

The late 19th-century censuses were scrapped for wood pulp during World War I. The surviving censuses, 1901 and 1911, are free on the National Archives of Ireland website. While these censuses took place after the vast majority of Scots-Irish had immigrated to America, they can help you find family members left behind and determine villages of origin for departed immigrants.

Missing Record Substitutes

The good news is that more records survived from Ulster than from any other part of Ireland. In addition, for every record group that has been lost, there are some workarounds and substitutes.

For example, the record group called Griffith’s Valuation is a great census substitute for those early censuses. Organized by “townland” (a subdivision of the Irish counties), this mid-1800s valuation shows names of renters (therefore, heads of households) as well as landowners. You can search Griffith’s Valuation free at Ask About Ireland. If you haven’t found an immigrant’s village of origin, you can at least learn which townlands contain the surname you’re looking for. Use Griffith’s Valuation as a substitute for early censuses destroyed during WWI. Search a free index to Griffith’s Valuation and other records at RootsIreland.

Going back to the beginning of the plantation of Ulster, see the free Ulster Ancestry website for links to records of those who took out land allotments in the early 1600s.

Of prime importance to those seeking Scots-Irish ancestry is the Public Record Office of Northern Island (PRONI), which has a personal name index for in-person visitors and has placed many of its holdings online, such as:

A Guide to Church Records identifies by name and year the registers held by PRONI and local congregations.

Church congregational histories provide additional historical background. You can find an alphabetized listing of these on the website of the Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland.

The National Library of Ireland has a detailed online catalog that can guide you to sources such as Irish manuscripts and articles in Irish periodicals. The library also has a significant collection of landed estate papers of families who owned multithousand-acre tracts before the 20th century, some of which will mention the tenants on those lands. PRONI actually has the best collection of these records; unfortunately, its Guide to Landed Estate Papers is only accessible on site.

Birth, marriage and death registration began in 1864, with non-Catholic marriages starting in 1845. Their location varies by the time period. The General Register Office of Ireland has master copies of Ulster vital events up to 1921. The General Register Office of Northern Ireland takes over from there, though it also has local copies of birth and death registers back to 1864.

A series of tax lists and population records provide early snapshots of Scots-Irish: the hearth money rolls (begun in the 1660s), the census of Protestant householders from 1740, the religious census of 1766, petition of Protestant dissenters (1775) and the 1796 Flaxgrowers’ List. All of these records are at PRONI.

Finding Scots-Irish Ancestors in Scotland

The final step in Scots-Irish research is tracing your ancestors back to Scotland itself. Church registers are the primary record group for this purpose, and fortunately, a variety of indexes and online sources are available. FamilySearch and its predecessor, the Genealogical Society of Utah, have created the Index to the Old Parochial Registers of Scotland on microfiche; Scottish Church Records is a CD version. Both are available at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library and through its local Family History Centers. FamilySearch’s online International Genealogical Index has abstracts of these same church records. Some records date to the mid-1500s, though a start of 1650 is more typical. For-pay service Findmypast offers digitized version of these church records.

Tracing Scots-Irish roots isn’t for the faint of heart—but then again, those to-the-brink-and-beyond ancestors wouldn’t want descendants who’d be ready to throw in the kilt at the first sign of a challenge. So be prepared to hone your genealogical battle skills in the United States and the British Isles. Then you’ll look forward to taking a wild ride worthy of the pioneering style of the Scots-Irish—or Ulster Scots.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT