Getting Started

Italy has a way of capturing your heart with its miles of vineyards, picturesque coastal towns, tranquil countryside, ancient ruins, stunning art and architecture, delicious foods (gelato, anyone?) and melodious music. If you have Italian ancestry, you may have cherished memories of a childhood in an Italian-American community. Or maybe you remember your nonna (grandmother) making pasta sauce.

As you unravel the stories of your ancestors, you’ll learn about the sacrifices they made to provide more opportunities for their children and grandchildren. These opportunities weren’t possible in the Italy that they left behind.

To start your Italian genealogy research, you’ll need to know the basics on Italian immigration to America and your ancestor’s town of origin. You’ll also need to learn how to access key genealogical records in Italy. So what are you waiting for? Cominciamo (let’s get started)!

How to Find Italian Origins

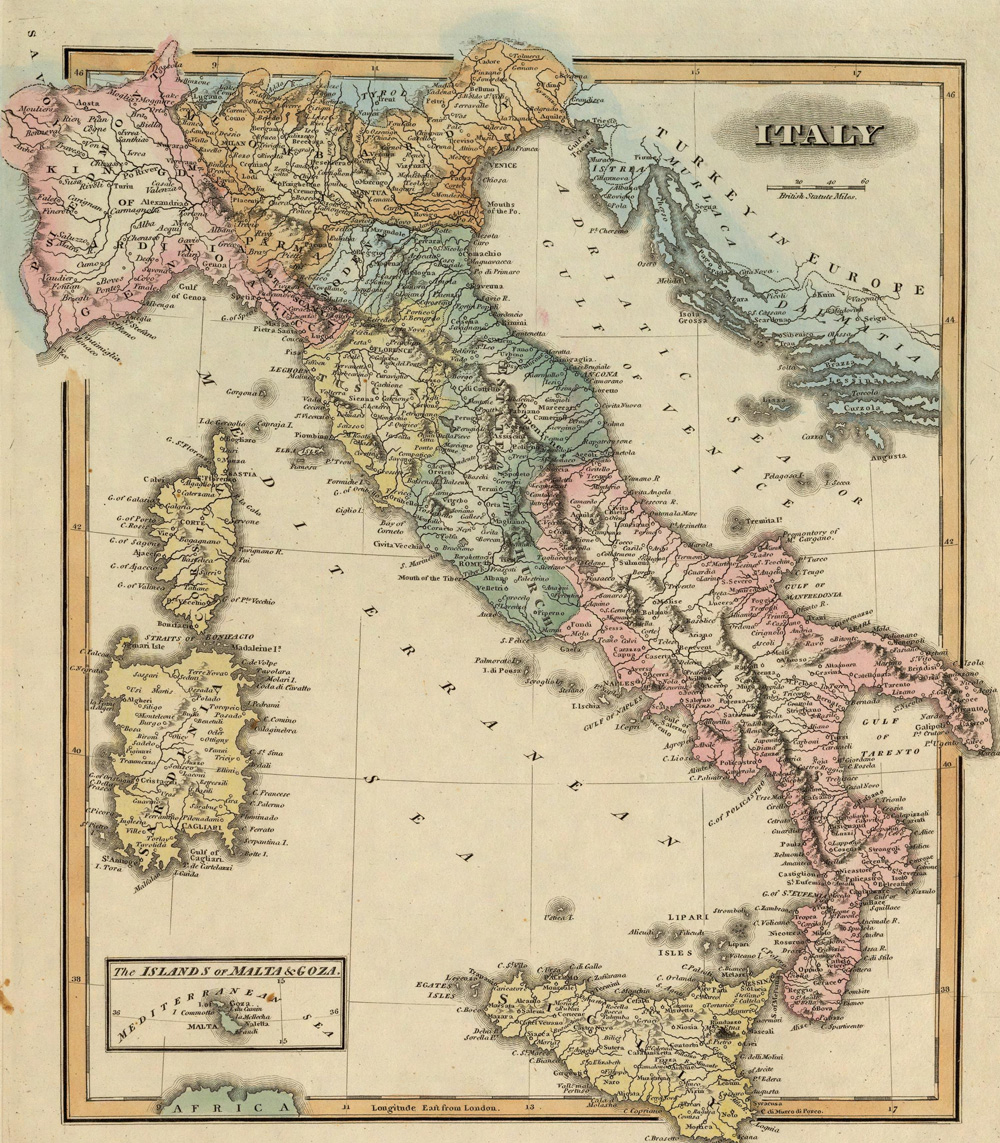

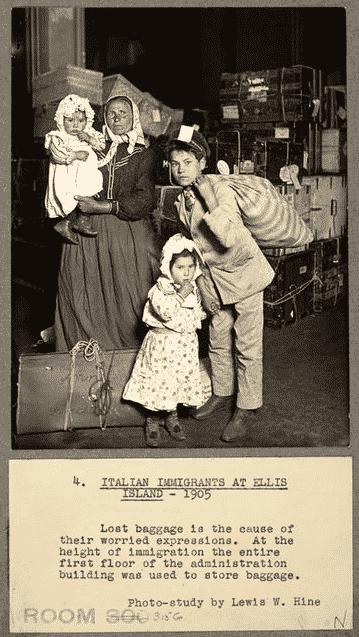

The largest wave of Italian immigration to America occurred between 1876 and 1930. That is when nearly 5 million Italians entered through American ports. Poverty often motivated an Italian’s decision to emigrate. Most immigrants were from southern Italy and Sicily (Sicilia, to Italians), which tended to be the poorest areas of the country. More immigrants came from Sicily’s Palermo (also Palermo in Italian) province than from any other province on the island.

Some immigrants never intended to make the United States their permanent home, immigrating seasonally to earn money to take back to Italy. Some worked as sailors to earn their passage, keeping more money in their pockets when they arrived home. These “birds of passage” and their trails often lead to multiple US and Italian ports and cities, placing them among the hardest Italians to track.

Common Italian Ports

The ports of Genoa (Genova) and Naples (Napoli) were the most common Italian ports of embarkation. Some ships stopped first in Palermo to pick up passengers before moving up the coast to Naples where they loaded the majority of the passengers and supplies for the transatlantic journey. Occasionally, you’ll see northern Italian families leaving from Le Havre, France. The port that an ancestor left from was usually the closest major port. Therefore, it can provide a valuable clue to his Italian town of origin.

Italians often settled in large communities in US cities such as New York City, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago and New Orleans. Each of these cities had an area that became known as Little Italy, often with those from a particular town or province living in close proximity to each other. Italians call this sense of identity and pride in one’s birthplace campanilismo.

Find Your Italian Town of Origin

The key to researching your Italian ancestors is knowing what town they came from. This is because th town or parish created nearly all of the useful records, so finding those records is difficult if you don’t know that information. Therefore, finding that information is an important first step.

Start your search with your US family’s records. Interview your oldest living relatives. Dig in the attic for old documents inherited from your Italian ancestors. Often you can find the town of origin noted in family papers or on the backs of old photos. Some Italian immigrants even kept their military discharge papers, passports or Italian identification booklets, all of which can provide clues to their origins.

To help narrow the choices of ancestral towns, use the Comuni.Italiani website. Let’s say that your ancestor’s immigration manifest says he was born in Polizzi and the ship he sailed on left from Palermo. On Comuni.Italiani, you can search for all towns beginning with or named Polizzi. The only possibility is Polizzi Generosa, a town in the Palermo province of Sicily. However, keep in mind that sometimes you’ll find multiple towns starting with a certain name.

Take, for example, Santo Stefano. At least eight towns in Italy begin with these two names. Knowing the immigrant departed from Genoa could help to narrow the list of towns in which to begin your research.

Unpuzzling Italian Places

Once you know the town of origin, you can discover the civil and religious jurisdictions that created your Italian family’s genealogical records. Italian civil jurisdictions include:

Town/city (Comune/cittá): The designation of a place as a comune or cittá is similar to an American town or city. This is determined by population numbers. Within a comune or cittá, you’ll find the common subcategories of frazione (a hamlet or village) and quartiere (neighborhood). These areas were under the jurisdiction of the town or city to which they belonged. Sometimes the hamlet where your ancestor was born is the location he gave as his birthplace or last residence when booking passage to America.

Province (Provincia): An Italian province is similar to a US county. Currently, Italy has 110 provinces. Each province has a provincial/state archive (archivio di stato) in its capital city (capoluogo). The name of the archive usually corresponds with the provincial name. Therefore, you’ll find the archivio di stato for the province of Reggio Calabria in the capital city of Reggio Calabria; it’s named the Archivio di Stato di Reggio Calabria. You can send record requests to these archives, but they won’t do extensive research for you. Their websites often contain databases or documents detailing their collections.

Region (Regione): Italy has 20 regions. Five of these regions — Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Aosta Valley and Fruili Venezia Giulia — are relatively autonomous and have their own legal statutes by which they govern.

Tip: Just like we have cities, counties and states in the United States, Italy also has civil jurisdictions: comune (town), provincia (province) and regione (region).

Religious Jurisdictions

You’ll also want to determine the parish and diocese your ancestor lived in. This is an important resource for finding church records in the predominantly Catholic country of Italy.

Parish (Parrocchia): The local parish is where your ancestors attended services, baptized their children and married. Smaller towns may have only one or two parishes; larger cities could have dozens. If your ancestors come from a large city, find out what neighborhood they resided in. This will help you narrow the choices of which parishes you’ll need to research.

Some civil records provide an address where the family resided and can be used to determine the neighborhood. To find a town’s parishes, check the official website of the Catholic Church in Italy as well as the parish search engine site. Keep in mind these websites list active parishes, and you may find that your ancestor’s parish is no longer in use. In some towns, all old records are consolidated in the Mother Church (Chiesa Madre), cathedral (Duomo) or cathedral (Cattedrale).

Diocese (Diocese): A group of parishes in an ecclesiastical district is called a diocese. Each diocese has a diocesan archives (Archivio Diocesano/Archivio Storico Diocesano). Marriage dispensations and records of closed parishes are often in the diocesan archives. While few of these records are online, you can access most in person, by appointment.

Occasionally, certain records will be held in an archive at the Archdiocese. One example of this is the diocesan archive at the Archdiocese of Lucca, which has parish birth, marriage and death records dating back to 1740. We’ll cover more on Italian genealogy church records below.

Understanding Italian Records

Italian Civil Records

Italy doesn’t have a single archive that’s comparable to the US National Archives and Records Administration, so genealogical records are most accessible at the provincial or town level. Birth, marriage and death records are some of the most useful for Italian research.

Italian archives categorize civil registrations into three different groups, depending on location and/or time period:

Napoleonic civil records (Stato Civile Napoleoico) were kept between 1804 and 1815. Many areas of northern Italy ceased civil registration in 1815 and didn’t begin again until 1866.

Restoration Civil Records (Stato Civile della Restaurazione, also called Stato Civile Borbonico or Bourbon civil records) were mainly kept in the area known as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies between 1809 (1820 in Sicily) to 1865.

Italian civil records (Stato Civile Italiano) generally encompass all civil registrations after 1866 or the Unification of Italy. Two sets of civil records were created at the time of a birth, marriage or death. One set is held in the town hall (municipio), where you can generally find them in the civil records office (ufficio dello stato civile). The registry office (anagrafe) often contains town and federal census records, but accessing those records is difficult. They’re available only when researching on site. In smaller towns, the ufficio dello stato civile and anagrafe offices may be combined. Most Italian town halls have websites where you can find the address of the civil records office to request records.

Italian Vital Records

The second set of civil records was sent to the district court (tribunale) at the end of each year. They’re held there for 70 years, at which time they’re transferred to the provincial/state archives. For privacy reasons, Italy restricts civil records access to 70 years after the creation of the record. The following are the types of civil records you’ll want to look for:

Birth records: In the birth certificate (atto di nascita), you’ll find the person’s date of birth, the baptismal date (before about 1865), and the names, ages, occupation(s) and residence of the parents, among other information.

Marriage records: Italians kept four types of marriage documents: banns (atto di pubblicazioni/notificazioni), act of solemn promise to celebrate marriage (atto di sollene promessa di celebrare il matrimonio), records (atto di matrimonio) and supplemental documents (processetti/allegati).

Death records: A death certificate (atto di morti/morte) provides the date, place and time of a person’s death. Often neighbors, not relatives, reported a person’s death. These are kept in the same places as birth and marriage documents.

Other civil records: A “historical state of the family certificate” (stato di famiglia storico) records the vital statistics of a whole family. The certificate is a compiled record, meaning it was created from other records at the time of the request. Town population registers (registri di popolazione) or schedules (scheda) were often used to compile these documents. These are usually in town archives, but they may be at the provincial archive. A certificate of family status (certificato di Stato di Famiglia) is a residency certificate providing details about a person’s residence in a certain town. Italian consulates often request this document when a person seeks dual Italian-American citizenship. The certificates are typically available from the town registry office.

Italian Marriage Records

Marriage banns usually provide information about the names, ages, occupations and places of residence of the couple and their parents. Sometimes you will find more information in the banns than in the marriage record. Prior to about 1865, marriage banns may contain two or three parts. However, after 1865 they usually are in a single document.

The act of solemn promise to celebrate marriage is a promise to marry, not the actual marriage document. The couple filed their banns and marriage promise civilly, then proceeded to marry in the church. Information about the names, ages, occupations and places of residence of the couple and their parents are provided. The date of the couple’s marriage was subsequently added to this document. You’ll find this document for pre-1866 records in most parts of Italy, in the same places birth records are kept.

The marriage record is often available only after 1866, when the civil marriage record became the legal one. It provides the names, ages, occupations and places of residence of the couple and their parents. Supplemental documents had to be attached to the marriage documents, potentially providing information on three to four generations of your family tree.

Supplemental documents included the couple’s birth or baptismal records. If any parents were deceased at the time of the marriage, their death records would likely be attached. If the father was deceased, the grandfather would appear to give permission, or his death record would be also attached.

Church Records

Catholic church records will figure big into your Italian research. Parishes and/or diocese hold most records. A few diocesan archives’ websites to explore include the Diocesan Archives of Vittorio Veneto and Diocesan Archives of Lodi. These websites often give the address of the archive for requesting records, operating hours and limited information on their holdings.

Church records begin earlier than civil registrations in Italy. You’ll find that many church records were written in Latin, rather than Italian. A translation resource can help you interpret these records. Once you’ve identified your ancestor’s the parish or diocese, you can search for baptismal, birth, confirmation, marriage, death/burial and parish census records.

Baptismal records (Battesimi): Baptismal records document the date of baptism, parents’ names (although the mother’s surname is usually not given) and the names of their godparents. From 1815 to 1865, some dioceses in northern Italy chose to record both birth and baptismal records after the government ceased civil registration, so an ecclesiastical birth record may be available for that time period. Exact titles for these records vary.

Confirmation records (Cresima/Confirmazione): Confirmation records are often found for children between ages 8 and 12. The records contain the child’s name, age, father’s name and date of confirmation. Few of these records have been microfilmed or digitized.

Marriage records (Matrimonio): These documents serve as proof of the couple’s marriage within the Church. Parents’ names are not always included.

Death/burial records (Sepolture): Depending on the age of the record, it may read more like a burial record than a death record. These records are usually very minimal, providing only the name, date of death and sacraments given.

“State of the Souls” (Status Animarun/Stato delle Anime): Essentially a parish census, this is a wonderful source of genealogical information. These documents are especially helpful in areas of Italy that ceased civil registration from 1815 to 1865. Vital statistics of whole family units were recorded, as well any sacraments they received. In Sicily, these records include less information and were called the Riveli di Beni ed Anime.

Italian Military Records

Military records might exist for male ancestors born after about 1850, although conscription wasn’t universally enforced until 1865. They were kept by province and military district, rather than by town. These records are useful when you know your ancestor’s province of origin, but not the town. They’re at the provincial/state archives. Military records include:

Extraction Lists (liste di estrazione) were kept in most areas of Italy between 1855 and 1911, and recorded an ancestor’s name in the order in which his number was assigned in the military “toss.” These records are sometimes difficult to find but may help to clarify information on an ancestor, especially when there is record loss.

Conscription records (liste di leva, also called registro di leva) may include the man’s name, date and place of birth, current residence, occupation, parents’ names and even a physical description. You also can usually find information on whether the soldier was deemed eligible to serve and the regiment he was assigned to.

Service records (ruoli matricolari or registri dei foglio matricolari) recorded a soldier’s regiment, military campaigns, injuries sustained and medals earned.

Discharge papers (foglio di Congedo Illimitato) document a soldier’s discharge from the Italian military, and may include service information. Immigrants often brought these papers with them to the United States as proof that they had already served their time in the military, in case they were conscripted again.

Accessing Italian Genealogy Records

FamilySearch

The easiest way to access Italian records from the United States is through Family History Library (FHL) microfilm and online at FamilySearch.org. The FHL’s microfilm collection is the largest collection of Italian records outside of Italy. To find available records, search the FamilySearch catalog for your ancestors’ town of origin. A few church and military records are available through the FHL, including military records for eight provinces, plus the Aosta region and city of Messina.

Many provincial/state archives have been digitizing records for years. Often they began with military conscription records, the focus of research requests from around the world. For example, the Cosenza province’s digitization project is one of the largest and is free for anyone to view. You just have to register with the website. The Gorizia province has a PDF index to service records and a searchable database of conscription records.

FamilySearch.org frequently adds Italian civil records due to a 2012 agreement with the Italian government. The agreement allows FamilySearch to digitize records in every provincial and state archive. The records, including digital images, are online at FamilySearch. You’ll need to visit a FamilySearch Center to view newly added records, per the terms of the agreement. They’re also on an Italian government website.

To see a list of Italian records available on FamilySearch.org, click on the Search tab and select Records. Scroll to find Search by Place and then select Browse Places. Choose Continental Europe on the map, then select Italy from the menu that appears on the right side.

Ancestry.com

Ancestry.com has more than 150 databases of Italian records, including civil registrations. Most of these records are separated by town and province, but some have been combined and indexed into databases by record type. A few other databases of interest include Italy Historical Postcards, Order Sons of Italy in America Lodge Records and Order Sons of Italy in America Mortuary Fund Claims.

For immigration records, search for New York arrivals in an index to Castle Garden records (1820–1892) or in Ellis Island records (1892–1924). You also can search immigration records for other large ports such as Philadelphia and Boston on FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com. Some Italians also are listed in Ancestry.com’s “New South Wales, Australia, Unassisted Immigrant Passenger Lists” database.

How to Request Records

If you can’t find records online or on microfilm, you’ll need to request them from an Italian archives or parish. Write in Italian; this letter-writing guide will help you. Don’t send money for postage unless it’s requested. Include your email address in your letter, and the recipient will let you know if you must send postage before the request is fulfilled.

To request military records, write to the provincial archives. Write to the parish or diocesan archives for church records. For civil registrations, write to the municipio or town hall (use the Comuni-Italiani website to find the sito ufficiale or official website of the commune). Ancestry.com’s Italian website also has a free list of the archives with their contact information.

If you reach a brick wall, don’t be shy to ask for help on Italian genealogical websites or blogs. Someone who reads your question may have just the answer you are looking for. A professional genealogist from the Association of Professional Genealogists, the International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists or the Board for Certification of Genealogists who specializes in Italian research may also be able to help you and offer suggestions that will enable you to move your research forward. Buona fortuna (good luck) in your research.

Tip: Typically, Italians named the first son for the paternal grandfather, the second son for the maternal grandfather, the first daughter for the paternal grandmother, and the second daughter for the maternal grandmother. If a child died in infancy, the next child of the same gender might be given the name of the deceased child.

Italian Genealogy Resources

Language

Italy is a rather young nation, having been formed from multiple city-states in the 1860s. This means you’ll find differences in cultural mores and spoken dialects from one area of Italy to another. As you delve into Italian research, you’ll need to learn Italian genealogical terms and numbers to find and understand the records. You also may need to know a bit of Latin to decipher parish records.

Many beginning Italian genealogy books provide sample record translations and record request templates in Italian. Also look for old Italian and dialectical dictionaries on Google Books. Google Translate can help you translate words, phrases and websites. In addition, consult these websites to learn the key Italian genealogy terms you’ll need to know:

• About.com Italian Numbers

• Ancestry.com: Italian Genealogy Terms—Occupations

• Corriere Della Serra/Dizionari (Dictionary)

• FamilySearch: Italian Genealogical Word List

• FamilySearch: Italy Language and Languages

• Italian Extraction Guide

• Italian Genealogy Letters

• Italian Occupations

Websites

- Ancestors Portal (Portale Antenati)

- Archivio di Stato di Cosenza Records Search

- Archivio di Stato di Gorizia: Liste di Leva Search

- Digital History: Italian Immigration

- FamilySearch: Italian Records and Research

- Immigrant Ancestors Project: Napoli and Torino Passport Requests

- Italian Genealogical Group

- Italian Genealogical Society of America

- Italian Genealogy Home Page

- ItalyGen

- Library of Congress: Italian Immigration

- RootsWeb Mailing Lists

- Transcribed Vital Records of Italian Towns

- Understanding Italy

Books

- Discovering Your Italian Ancestors: How to Find and Record Your Unique Heritage by Lynn Nelson (Betterway Books)

- Finding Italian Roots by John Philip Colletta (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Finding Your Italian Ancestors: A Beginner’s Guide by Suzanne Russo Adams (Ancestry)

- Italian-American Family History: A Guide to Researching and Writing About Your Heritage by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Italian Genealogical Records: How to Use Italian Civil, Ecclesiastical and Other Records in Family History Research by Trafford R. Cole (Ancestry)

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.