Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The theme song to NBC’s “Apprentice,” starring over-the-top rich man Donald Trump and a gaggle of go-getting Trump wannabes, drives home how important the green stuff is. We seemingly devote half our lives to making it, and the other half to worrying about it (or ostentatiously spending it, in The Donald’s case).

If it’s so difficult to make ends meet nowadays, imagine life for our forebears. Way back when, it wasn’t uncommon for a major bank collapse to send the country into an economic tailspin and your family into a struggle to get by. Wages were low, but then again, goods were less expensive, so your ancestor’s net worth would stretch further — right? How do you know whether your family lived large Trump-style, or scrounged for every meal like the castaways on the CBS hit “Survivor”? The answers are in documents you’re probably familiar with: census, tax and estate records, plus social history resources. All of these can do more than just give you names and dates. They’ll also tell you about your ancestors’ economic standing — if you know how to tease out the clues.

Making dollars and census

ADVERTISEMENT

For basic information on your ancestors’ finances, you need look no further than that most popular of genealogical tools, the US census. Starting in 1850, every census had a column for occupation. The 1880 enumeration asked people who were unemployed during the census year to list how many months they’d been out of work. Variations of this question appeared in the 1900, 1910 and 1920 censuses. The censuses in 1850, 1860 and 1870 required property owners to list the “value of real estate.” The latter two asked all heads of household to list their “value of personal estate.” According to Kathleen W. Hinkley’s Your Guide to the Federal Census (Betterway Books), that could include items such as “stocks, bonds, mortgages, notes, livestock, plates (china),jewels, and furniture, but not wearing apparel.” In 1860 slaves were included, too. This column was left blank if the property totaled less than $100. In enumerations from 1900 to 1930, residents indicated whether they owned or rented their homes, and if the abodes were subject to mortgage.

Manufacturing, industry and agriculture schedules, often called special censuses, are rife with economic information. For the 1820 industry schedules, census takers asked for the number of employees, amount of capital invested and type of articles manufactured. From 1850 to 1880 (and 1885, for the few states participating in that census), you’ll find even more detail. The agricultural schedules covered the number of livestock, amounts of produce, value of total production and more. Business schedules (called industry schedules from 1850 to 1870 and manufacturer schedules in 1880) included questions on the number of employees, type of articles produced and capital invested.

You’ll find microfilmed census records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> and its regional facilities. Most major libraries, including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City, have them, too. You can borrow FHL microfilm for viewing at branch Family History Centers (FHCs); see the FamilySearch Web site to find one near you. Search the census online using the subscription sites Ancestry.com and Genealogy.com; or access the records for free through libraries that subscribe to HeritageQuest Online or Ancestry Library Edition.

ADVERTISEMENT

Glass Act

In 1798, the fledging American government authorized the US Direct Tax (nicknamed the Glass Tax or Window Tax), hoping to replace the Income from the unpopular levy on distilled spirits that led to the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. The Glass Tax was repealed In early 1799, leaving just one year of returns — but, oh, what a snapshot they provide. The assessment on the document’s Particular List shows:

- owner’s name (and occupant, if he or she isn’t the owner)

- number of dwelling houses and outhouses worth less than $100

- dimensions and descriptions of dwelling houses and outhouses (which can help you identify surviving structures)

- the houses’ values

- number and descriptions of all other buildings and wharves

- an adjoining property owner’s name (useful for finding the property on a map)

- property acreage

- type of soil

Some of the lists even say whether the house was built with round or squared logs. Ironically, the number of glass panes taxed goes unmentioned.

Pennsylvania claims the largest surviving body of Window Tax returns; they’re on microfilm at NARA and Pennsylvania’s state archives. Many historical and genealogical societies have indexed their counties’ records. Massachusetts also has substantial returns (they’re part of the New England Historic and Genealogical Society‘s members-only databases), as do Maryland and portions of Georgia, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont and Connecticut. Find them at state archives and see the resources listed on the opposite page. Click here for more on the Glass Tax.

Collecting taxes

Much of the information from that Civil War-era income tax might have been published for all your ancestors’ friends and neighbors to see. In Berks County, Pa., for instance, the 1863 listings (including incomes) for everyone subject to the tax appeared in the Feb. 18,1865, Berks and Schuylkill Journal. To look for your ancestors’ records, check local historical societies for abstracts of tax listings from newspapers and other sources. Click here for NARA’s information on researching this income tax. Keep in mind many people were exempt, as the tax applied only to incomes of $600 and above.

Since state and local governments levied most pre-20th century taxes, the records they generated are localized, too. Many tax lists from centuries gone by are still in custody of the original county courthouse office in charge of taxation. In same states, tax lists are at the state archives or published in books such as the Pennsylvania Archives series, parts of which are available on CD from Retrospect Publishing. Search online library catalogs and booksellers’ Web sites — type in your ancestor’s state or county name and the search term tax records.

The USGenWeb Project‘s county Web sites are great sources of transcribed tax lists, though the amount of information on these volunteer-run sites varies. The site for northwest Ohio’s Lucas County, for example, has a transcription of an 1837 poll tax list (the now-illegal fee certain jurisdictions once required before voting). To access a county site, go to USGenWeb, click on your ancestral state and look for a county list (some sites have handy clickable county maps).

Estating the facts

Few record groups surpass estate papers for gauging economic standing. Even if your ancestor died intestate (without a will), the process of distributing his worldly goods could have created a number of helpful records. Look for these documents:

- A will, if your ancestor had the fore thought to write one, can be as simple as 2 single sentence (“All to wife”) or as complex as a detailed list of the deceased’s land, goods, investments and more.

- An estate inventory outlines the deceased’s possessions and their values. In addition to belongings, inventories show debts (often in the form of bonds or notes) owed the deceased. (See the toolkit, right, for resources that will help you demystify these documents.)

- Vendue lists are especially interesting because they include prices your ancestor’s personal property fetched at auction. In some cases, you’ll find the values shown on the estate inventory differ vastly from the actual prices paid.

An estate executor or administrator had to file an account — or sometimes several, if the estate wasn’t settled quickly — of how the assets were distributed. These documents are filled with details; far example, some men created “life estates” granting their widows use (but not ownership) of a house and other real estate. Rent from land leased for farming would be recorded as income to the estate.

Estate papers are usually at the ancestor’s county courthouse, but schemes for organizing them vary widely. The best-cast scenario is when you find all the estate papers (such as a will, inventory, vendue lists, legal petitions) together in one file. But at some courthouses, each type of document is filed separately—all the wills in one place, the inventories in another, and so on. Luckily, papers for many counties are on microfilm at the FHL. Run a place search of the online catalog on the county name, then look for the court records, wills and estates headings.

Learning home economics

If numbers from census records, estate documents and tax lists are to speak clearly about your ancestors, you’ll need some historical context. We’re used to the last 70-something years of nearly uninterrupted gentle rises in wages and prices. But the boom-and-bust economic cycle was far more vicious up until the Great Depression of the 1930s. Though most of today’s senior citizens remember those hard times, they and younger folks haven’t lived through the type of peaks and valleys that happened every 20 years or so throughout the 1800s. During these early crises (often called panics, some of which are listed below), wages and prices plummeted, businesses defaulted and unemployment spiked. A major company going belly-up could trigger the downward spiral: The Aug. 24, 1857, failure of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Co.’s New York branch, for example, sparked a panic in 1857. Learn more about historical panics and depressions.

The centerpiece of the American dream — the family home — was part of this up-and-down equation. Be especially careful when you research deeds and land records, and see real estate prices from your ancestors’ era. Learn the circumstances surrounding a particular sale and the history of the place where it happened. If you know the nation was in one of those periodic panics, that may explain a low price for a home that earlier brought twice the amount. County histories and old newspapers provide a wealth of information on ups and downs in your ancestor’s area.

Another crucial fact to remember: American society gets more and more agrarian the further back in time you travel. For many of our ancestors, “making a living” didn’t mean “earning an income.” The need for income could be almost nil for a farmer who raised enough crops to feed his family, and his wife, who made the family’s clothes. Even many craftsmen farmed enough to subsist.

Relative values of items have fluctuated over time. Farm animals, for instance, were much more highly valued in the 18th and 19th centuries than they are today because of their usefulness for transportation and farm labor.

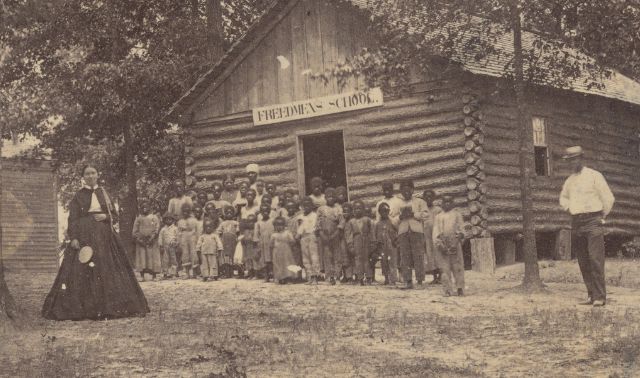

Several professions have risen in status, too. Doctors and lawyers, for the most part, were members of the middle class in yesteryear. Now, with these careers’ demanding training requirements, they usually pay top dollar. From 1850 through 1870 and in 1885, the government created social statistics schedules, gathering information such as the number and kind of an area’s schools, libraries and newspapers; seating capacity of churches; numbers of paupers and expenditures for their support; and wage information. In 1870, for example, an Ada County, Idaho carpenter could make $6 a day—but not far away in Aduras County, he could pull in $8. The Government Printing Office 1886 Report on the Social Statistics of Cities, compiled by George E. Waring Jr. from 1880 census information, gives details on 222 cities. You’ll find this publication at most federal depository libraries.

Comparing your ancestor to others from his area and era not only lets you translate his worth into today’s dollars, but also see what that amount of money meant at the time. A 1700s tax list showing your ancestor owned 250 acres may seem impressive until you notice most others in his township had 300 to 500 acres. Whether it’s tax bills or land or some other measure of wealth, look at records for an entire neighborhood. This type of “macro” approach will give you a better handle on your ancestor’s financial well being than studying him in isolation. Likewise, when you check mid-19th century US censuses for the values of your relatives’ real estate, make notes of the information on nearby property owners.

Of course, your ancestor’s net worth might look like peanuts if he lived down the road from an 18th-century Donald Trump — or maybe your great-great-grandfather was the neighborhood’s high roller. Either way, now that you understand your forebears’ financial fortune, genealogical wealth will trickle down to you.

Toolkit

Web Sites

- 1798 Tax Assessment for Northern New York, <www.rootsweb.com/~nyclinto/1798tax.html>

- Cyndi’s List: Taxes, <www.cyndislist.com/taxes.htm>

- Cyndi’s List: Wills & Probate, <www.cyndislist.com/wills.htm>

- Department of the Treasury: History of the US Tax System, <www.treas.gov/education/fact-sheets/taxes/ustax.shtml>

- EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic and Business History, <eh.net/encyclopedia>

- Maryland State Papers (Federal Direct Tax), <guide.mdarchives.state.md.us>: Under State Agency Series, click on State Agency Records on Microfilm. Then under Maryland State Papers, click SM56-Federal Direct Tax, 1798.

- Tax History Project, <www.taxhistory.org>

Books

- 1798 Direct Tax New Hampshire District #13 compiled by John S. Fipphen (Heritage Books, out of print)

- The Beginner’s Guide to Using Tax Lists by Cornelius Carroll (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Estate Inventories: How to Use Them by Kenneth L. Smith (Masthof Press)

- History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928: Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics #499 by Estelle M. Stewart (US Government Printing Office, out of print)

- Your Guide to the Federal Census by Kathleen W. Hinckley (Betterway Books)

1792 Panic ensues when big speculator William Duer goes insolvent

1819 The Second Bank of the United States tightens credit and spurs a panic

1837 Land speculation creates the panic of 1837

1857 The Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Co. bankruptcy leads to a panic

1866 Internal revenue collections peak at $310 million

1873 Philadelphia firm Jay Cooke and Co. goes bankrupt; panic follows

1884 Strikes sweep the country amidst severe depression

1893 Falling crop prices help fuel the panic of 1893

1907 A failed scheme to corner United Copper Co. stock leads to the panic of 1907

1929 Black Tuesday starts the Great Depression

1933 The Glass-Steagall Act creates the FDIC to insure bank deposits

1950 The Diner’s Club introduces a credit card accepted at 14 restaurants

EH.Net’s online tool How Much Is That? can tell you. Just choose What is the Relative Value? (for US dollars), then key in your price and year, and choose CPI (consumer price index). You’ll learn that Great-grandma’s dress, brand-new, would cost $3,800 today. Similar calculators are at <www.westegg.com/inflation> and <www.minneapolisfed.org/research/data/us/calc>.

Use The Value of a Dollar: 1860-2004 by Scott Derks (Grey House Publishing) to affix costs to family lore. This book lists what your ancestors paid for everything, including silver-plated dinner knives ($3 a dozen in 1881), a steak dinner ($1.50 in 1915), a dozen eggs (23 cents in 1910) and a new brick home ($2,500 in 1880). The new suit Great-great-great-grandpa Ed sports in the 1880 photo would’ve set him back about $12.50. You can assess heirlooms, too. For example, your antique music box cost your Civil War kin around $5.

Historical prices seem low, but your ancestors had far less to spend than you do. To appreciate this, go back to How Much Is That? and price Great-grandma’s 1885 wedding dress, this time using the Unskilled Wage option. Measured this way, her $200 dress purchase equals your spending $23,500. And Great-granddad’s Model T ($850 in 1908) would be the same as an $80,000 car to you. A few dollars for your ancestors adds up to a modern-day fortune. Understanding that math will give you new respect for their lives.

The Value of a Dollar also can supply your ancestor’s earnings in various occupations: A bricklayer made $1.53 an hour in 1860; a telegraph operator, $592 per year in 1905. A 1901 teacher pulled in around $700 a year — roughly $13,000 today.

ADVERTISEMENT