Successful identifications result from partnerships: Readers supply their family data, and I sort through the clues. Faithful readers know it’s possible to identify a picture based on their knowledge of family history and attention to photographic details, such as image type, photographer’s imprint and costume clues.

The following eight strategies have brought me success, either by dating a picture, identifying the subjects or eliminating suspects. Employ these surefire methods to tackle your own mystery pics.

1. Consult family.

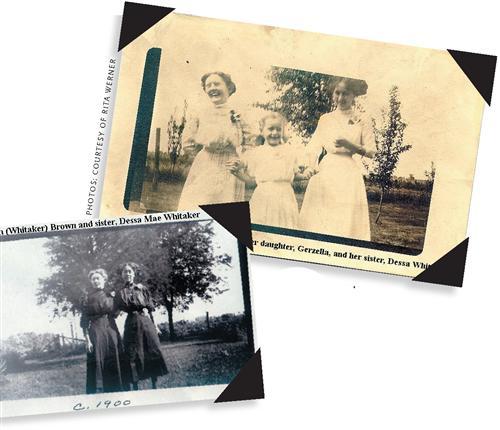

In 2001, Rita Werner sent me a candid photograph of two women and a young girl. Werner had found the image in an album that belonged to her grandparents, both born in 1910. At the time, she wrote, “It’s possible that this picture is of my grandmother’s mother, who was orphaned in Indiana and raised by family members in Illinois.” She had shown the picture to several relatives, but no one could identify its subjects. Yet they did notice a resemblance to her grandmother’s side strong resemblance to her grandmother’s side of the family.

Werner specifically wanted to know if the picture predated World War I. The little girl’s hair bow and the length and style of the women’s dresses dated the image to 1900 to 1910. Although I answered Werner’s question, I couldn’t identify the image’s subjects.

The photo seemed to be a dead end. No one could identify the group, and having a date didn’t help, either. Then a cousin mailed Werner the missing piece to the puzzle — an early 1900s picture of her grandfather’s family (see above left). Werner sent me a jubilant e-mail: “When I saw this picture along with the original one in question, I knew beyond a doubt that I had the identity! Notice the tiny waist on the woman on the right in both pictures. Also, the hairstyle of the woman on the right is the same in both pictures.”

Connecting with family and comparing images resulted in a positive identification. The women belonged to Werner’s grandfather’s side, not her grandmother’s, as others had suggested. Werner discovered that the woman on the left in both pictures is her great-grandmother Adah (Whitaker) Brown, born in 1880. The woman on the right is Adah’s sister Dessa Mae Whitaker, born in 1885. The child in the first picture is Dessa Mary Gerzella Brown, the only sister of Werner’s grandfather. She was about 5 years old when the picture was taken. Werner recalled that her great-aunt never went by Dessa Mary, only Gerzella. “Now when I look at her with fresh eyes, I can see the resemblance to my grandpa!” she wrote. “Gerzella was born in 1904. So now I know that it’s Gerzella holding onto her mother’s and aunt’s hands in a picture taken prior to 1910 because that’s when Grandpa was born – and as you can see, Adah is definitely not pregnant.”

2. Use genealogical resources.

Some of the same resources used to collect family history information – such as city directories, newspapers and vital records – can solve picture puzzles, too. The photographer’s imprint “M. Chandler, Marshfield, Mass.” on the man’s portrait on the previous page started the identification process. By checking A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers by Chris Steele and Ronald Polito (Picton Press, $89.50), I learned that a Martin Chandler worked in Marshfield between 1853 and 1896. You can find information about the photographers of your family pics by consulting city and professional directories and the Web site Finding Photographers <www.findingphotographers.com>. Knowing when a photographer was in business can help narrow a picture’s time frame and the identification possibilities. In this case, a date appeared on the back of the image: 1879.

In 1879, Marshfield was still a small town, and it couldn’t have had many residents around this man’s age (I guessed he was at least 90). Working with that hypothesis, a colleague checked Vital Records of Marshfield, Massachusetts to the Year 1850 compiled by Robert M. Sherman and Ruth Wilder Sherman (Society of Mayflower Descendants), which actually included vital data beyond 1850. A quick scan of the listings provided a possible candidate: “Samuel Curtis, died 21 August 1879, aged 100, 22 days.”The final clue was Curtis’ obituary in the Boston Daily Advertiser Aug. 25, 1879. This sentence confirmed my hunch: “On his last birthday he had his photograph taken twice, once alone and once in a group.”

3. Get fashion conscious.

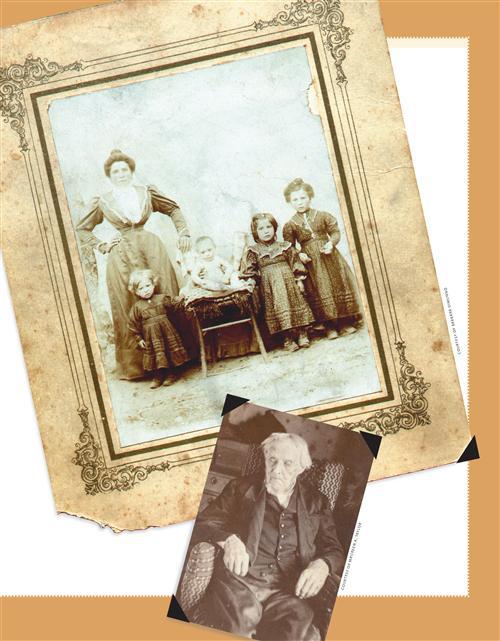

Recognizing fashion details, such as a leg-o-mutton sleeve or a shawl collar, and knowing when they were in style can help you date a photograph at a glance. When Barbara DiMunno submitted a group portrait of a woman and her children, owned by either her great-aunt Lillian (Clark) Hewitt (1873-1955) or Lillian’s mother, Harriet (Ogden) Clark (1842-1912), she asked for help dating the image.

The woman’s clothing provides the most clues. With one hand on her hip and the other on the photographer’s chair, she draws attention to her small waistline, which is held in by a restrictive corset. According to Support and Seduction: A History of Corsets and Bras by Beatrice Fontanel (Harry Abrams), these undergarments were popular from the 1870s through 1914, which provides a tentative time frame for the image.

John Peacock’s costume encyclopedia 20th Century Fashion (W.W. Norton & Co.) indicates that the mother’s dress — with the deep V-neck opening, white high-necked shirt with full collar, and tight lower sleeves with fullness at the upper arms — resembles dresses worn around 1906. These details suggest the picture was taken between 1900 and 1910, accounting for style variations within the decade. The three girls in this photograph wear dresses of similar design and fabric. Girls’ attire mimicked women’s fashions; notice that the oldest child wears her hair in a topknot like her mother’s.

At this point, DiMunno can’t name the family in the portrait. Hewitt would be the right age for the picture, but other portraits of her disprove this theory. Although the costume clues weren’t enough to identify these individuals, they did allow DiMunno to narrow the possibilities.

4. Know your photo history.

Determining the photographic method can establish an image’s time frame and correct a misidentification. Different types of photos were popular at different times. For instance, the earliest images — shiny metal daguerreotypes (1839 to 1860), glass ambrotypes (1854 to 1865) and iron tin types (1856 to mid-1900s) – all debuted in the mid-19th century, but only the tintype remained popular into the 20th century.

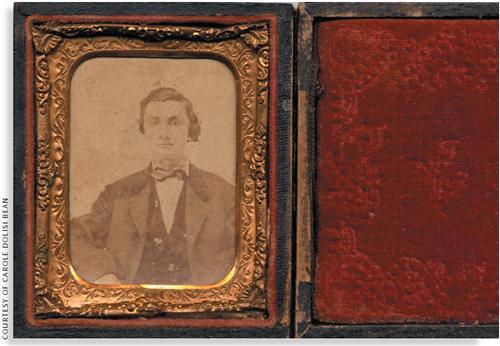

Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes and paper prints all came in cases like the one above, which Carole Dolisi Bean discovered in her grandmother’s sewing box. If you have to hold a cased image at an angle to view it, you know it’s a daguerreotype. Ambrotypes often have holes in their backing material; this makes them look transparent. Tintypes are magnetic. If at first glance you can’t determine the photographic method, resist the temptation to remove the image from its case. Doing so can cause irreparable damage to both the picture and the case. The cover glass is missing on Bean’s image, so I could tell that it’s a paper print.

Dating an image’s enclosure – frame, mat or case – also can aid the identification process. Cases came in a variety of sizes, shapes and designs. Two great guides to cased images are Floyd and Marion Rinhart’s American Miniature Case Art (A.S. Barnes, out of print) and Adele Kenny’s Photographic Cases: Victorian Design Sources, 1840-1870 (Schiffer, $59.95). The Rinharts’ book lists names and locations of case manufacturers — a handy reference tool if your case bears its maker’s name.

All the evidence in Bean’s photo case – the wood frame and ornate mat – dates the image to the 1850s. The man’s patterned vest, colorful tie, white shirt and loose sack coat with velvet collar suggest the picture was taken in the late 1850s. These clues disproved Bean’s theory that the subject’s her great-grandmother’s brother August Edward Moll (born 1847). Using the photo’s date, she’s still trying to discover the man’s identity.

5. Magnify your images.

The key evidence in the photograph at left, submitted by Valerie Moran, was so obvious that she initially overlooked it. Sometimes the smallest details can be your biggest clues. In this case, the details were the flags. By simply magnifying the image, counting the number of stars on each flag and reading up on Old Glory’s history, I discovered the picture was taken within a four-year time frame — July 4, 1908, to Jan. 6, 1912.

Everyone in this picture wears summer attire — most of the women have on white summer dresses or shirts, while the men pose without jackets. The women’s pouched-front blouses, wide belts, straight skirts and Gibson Girl hairstyles fit the flags’ time frame.

When identifying a photograph, I usually try to narrow the time frame even further. The flag’s history came in handy here. Oklahoma joined the Union Nov. 16, 1907, but the new flag didn’t debut until July 4, 1908. The subjects’ summer attire and crisp flags suggest these people were celebrating the Fourth of July, or maybe the introduction of the new flag.

Based on her family data, Moran suspects the photograph was taken in 1912. She thinks the young man on the right is Clifford John Caminade (born 1885), who would have been 27 that year, and the older man on the left is his father, Louis Cass Caminade (born 1852). Their apparent ages and the photograph’s date support this conclusion.

6. Examine props.

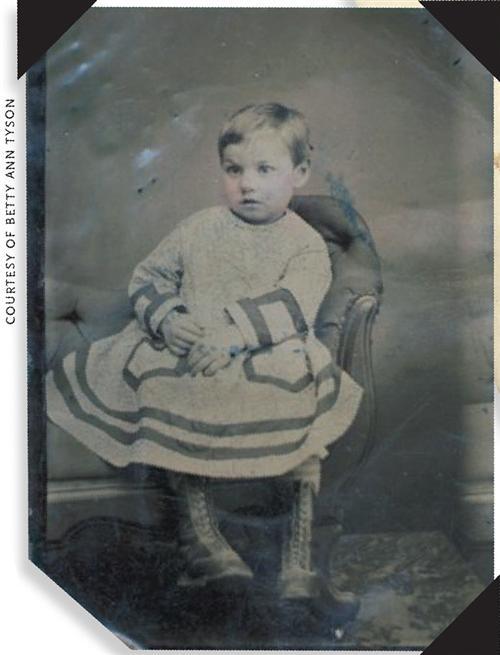

Many photos submitted for analysis have identifications, but no dates. Such is the case with Betty Ann Tyson’s hand-colored tintype, tentatively identified as “Grandma Tyson.” Positive identifications rarely rely on a single piece of evidence; you must add up all the clues before drawing a conclusion. Here, the child’s dress and chair date the picture. The girl wears a white summer dress with a wide, open neckline; ruffled (perhaps eyelet) trim; and shoulder bows — features of dresses popular in the late 1860s and early 1870s, according to The Child in Fashion 1750-1920 by Kristina Harris (Schiffer) and Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900 by Joan Severa (Kent State University Press.

The chair in this image was a common photographer’s prop during the same time period. Since it usually took a few minutes for a camera to capture a scene, photographers used furniture or special braces to hold subjects still. You’ll find examples of this furniture in Identifying American Furniture by Milo M. Naeve (Altamira Press) and The Tasteful Interlude: American Interiors through the Camera’s Eye, 1860-1917 by William Seale (Rowman & Littlefield). Judging by the furniture, clothing clues and subject’s age, we’re sure this image depicts Betty Ann’s grandmother Lizzie Tyson, who was born in 1867.

7. Network online.

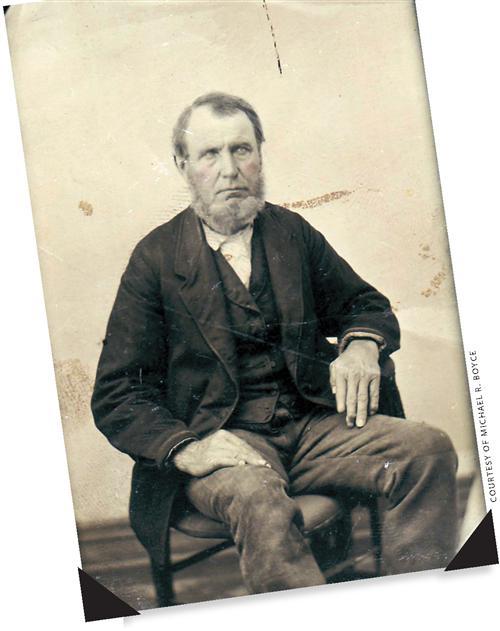

By connecting with cousins over the Internet, Michael R. Boyce has discovered that some of the seemingly far-fetched stories his father told him — including the one about their relation to a Dutch sea captain – are true. Through these “Internet cousins,” Michael also has uncovered a surname change, an unexpected link to his ancestor Stephen V.Boyce and a tintype (above) of a man he thinks is Stephen’s father, John Boice (born 1794).

Confirming that identification requires comparing family pictures to eliminate other prospects. Michael thinks the portrait above depicts his third-great-grandfather because he already has identified images of two of John’s three brothers. The third brother died as a young man, so this couldn’t be him.

Clothing clues further support the identification. This man wears work clothes suggestive of the 1860s. At that time, John would have been in his 60s.

Although Michael still can’t confirm this man’s identity, he’s off to a good start. Perhaps his photographic family tree posted on the Buys/Boice/Boyce Web site <webpages.charter.net/boyceweb> will help bring new information forward. Consider creating your own family Web site, or connect with distant kin through surname message boards, such as those at Roots Web <www.rootsweb.com>. Through photo-reunion sites such as DeadFred <www.deadfred.com> and AncientFaces <www.ancientfaces.com>, you might even find some long-lost images of your ancestors.

8. Be persistent.

It took Jackie Hufschmid three years, but she finally identified the young couple in a photo she’d submitted for my first Identifying Family Photographs column. Initially, I researched the photographer, Bonell, and the couple’s clothing to place the portrait in Eau Claire, Wis., between 1875 and 1890, but that’s as far as I got.

An amazing thing happened when the picture appeared online and then again in the August 2000 Family Tree Magazine. We received e-mails from several people who said they’d seen the photograph before – some even owned copies of it. A network of family historians developed, and they worked together to try to identify the couple. Hufschmid refused to give up.

In summer 2003, she finally found the missing link to Eau Claire. A cousin in Wisconsin revealed that two of their female relatives had moved there in the late 19th century – one to open a dress shop and the other to work in it. Upon hearing their names, Hufschmid realized that she had another picture of the couple taken years later. Once she placed the identified 1920s image of the couple and their children next to the original portrait of the young couple, she knew she had a match. The mystery people are Julia Gullickson (1872-1948) and her husband, James Wood (1868-1933). Scanning and enlarging sections of the images to compare facial features confirmed the identification.

Like Hufschmid and these other Family Tree Magazine readers, you can date and identify your own old family photos. Just put on your detective cap, pull out the magnifying glass and start sleuthing. All it takes is a little time, perseverance and old-fashioned genealogical research.

From the February 2005 Family Tree Magazine