Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Imagine stepping back in time to enter the lives of your ancestors as easily as stepping into your kitchen. Living history museums and re-enactments can make your heritage come alive with details about your ancestors’ experiences. You can find out what unfamiliar-to-us foods they might’ve eaten, what their clothing felt like, what current events they witnessed and what skills they needed to get through a day. Maybe you’ll learn how to make iron gall ink from the growths on oak trees, observe an artillery crew execute the precisely timed tasks of firing a cannon, or try carding wool and spinning it into yarn. All sorts of particulars about your forbears’ lives will materialize when you visit a living history exhibit.

Living history enthusiasm started in the 1920s when John D. Rockefeller began funding acquisitions and restoration at Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg. In 1929, Henry Ford founded Greenfield Village in Michigan to showcase American life in the mid-1800s. Today, small museums and interpretive sites across the country join large, well-known museums such as Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, Old World Wisconsin and This Is the Place Heritage Park in Salt Lake City. You can find living history museums representing every time period and culture from around the world—likely including your ancestors’. A bit of planning is necessary, though, to find a living history site near you and make the most of your visit. Whether you want a day trip or a weeklong history immersion, here’s how to take your family along on a journey to your family’s past.

1. Pinpoint places to go.

Ideally, you want to find a living history site that’s easy to get to, affordable, has activities that’ll appeal to everyone in your family and offers a path to understanding your heritage. But before you start looking, decide what’s most important: If you’re set on showing your grandkids how their ancestors lived, begin by searching for places related to your family’s ethnicity or the historical era of interest. But if time is your most limiting factor, first create a list of nearby sites and then choose one in line with your genealogical interests.

ADVERTISEMENT

Try to build visits into your family history research. When you travel to a library, conference or repository in a place your family lived, look around for museums or historical sites where you can learn about the people who lived there.

Where can you find living history museums? Pay a visit to the state historical society or natural resources department in your state or your ancestor’s state; those organizations usually manage state historical sites. To find family-heritage-related sites, run a Google search on living history and an ethnicity, event, era or place—such as Civil War, German or pioneer. Heritage-focused historical and genealogical societies, such as the Swedish-American Historical Society and Shaker Historical Society also can point you to places worth visiting.

2. Find out what there is to do.

Once you have a short list of sites, research activities each one offers for those that appeal to your family. When the activities are scheduled and what they might cost will help you select your final destination.

ADVERTISEMENT

Historical re-enactments might occur regularly in the form of a costumed gardener tending heritage tomatoes, a blacksmith forging a horseshoe or “Thomas Jefferson” delivering a famous speech.

Sites typically also stage special events such as plays, military battles (particularly during anniversary commemorations) or court trials. Conner Prairie Living History Park in Fishers, Ind., for example, has an annual Follow the North Star program in which participants take on the role of fugitive slaves. Museums might even hold classes in historical skills, such as the Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer’s tinsmithing workshops in Grand Island, Neb.

Are you bringing your children or grandchildren with you? There’s nothing better than a living history site to help the next generation learn about previous generations. From living history places we’ve visited, my children know how big an ox is, how to play graces, how it feels to lay in a rope bed and what horehound candy tastes like. Yes, kids can be difficult to entertain, but many museums work diligently to provide engaging activities for youngsters: Kids clubs, petting “zoos” of farm animals and old-fashioned crafts are some of the activities you might find. Historic Cold Spring Village near Cape May City, NJ, for instance, has an activity area where children can try on historical costumes and play games from yesteryear. Fort Nisqually in Tacoma, Wash., fires a “candy cannon” during summertime family nights.

Examine museum websites for events calendars, schedules of regular activities and kids programs. You’ll also learn about the site’s history and architecture, how to get around, and accessibility for visitors with special needs (unfortunately, few historic buildings will have ramps or elevators). While you’re online, look for details on hours, directions, nearby accommodations, restaurants and other local tourist activities. For advice from those who’ve visited the place, search online for the museum name and reviews, or use a website such as Virtual Tourist.

3. Plan your trip.

Now that you’ve chosen a destination, a little planning will go a long way to making your trip run smoothly and saving you money. Check online for information on reservations, tickets for events and workshops, tours, membership discounts (depending how long you’re staying, becoming a member might be worth the money), vacation packages, and any special closures of buildings or exhibits.

Prepare for the weather and wear comfortable shoes—you’ll be walking, standing and climbing stairs during your visit. Remember that many of the buildings you’ll enter were built long before air conditioning and central heating. Dress as if you’ll be spending the day outside, but wear layers you can remove inside a stuffy 200-year-old shop or put on inside a too-cold visitors center. Bring water and sunscreen for hot weather.

Be sure to plan enough time for your visit. Some sites are small enough to explore in an afternoon; others take a few days or longer to fully experience. You won’t feel you’ve gotten your money’s worth if you have to rush through, but you might be bored if you run out of things to see or do. The museum’s website might offer advice on how much time to allot, and check the online reviews mentioned in step 2. Think about your family, too:

- If you’re traveling with little ones or Grandma—or someone who likes to thoroughly read all the placards—you might need more time.

- Prepare a list of activities you want to do and scheduled times. Let each family member select one so everyone feels included.

- Be flexible: Prioritize your itinerary with must-dos, would-like-to-dos and could-dos. Plan around the must-dos; you can eliminate activities in the latter two categories if you run out of time or are faced with fussy youngsters.

- Also figure out when and where you’ll eat, and schedule breaks for kids to nap, run around or text their friends.

Most important, plan to connect your visit with your family history. Study up on those whose lives most relate to the place you’re visiting and select activities with them in mind. Tell your traveling companions about them. Get out photos of those folks and a chart showing how they’re related to make them more real. Help the kids brainstorm questions for the museum interpreters: Ask “How long did it take to raise a successful corn crop on freshly broken prairie?” to get a sense of your farming ancestors’ struggles, or “What kind of toys did kids play with?” to learn what childhood was like.

4. Make your visit.

When you arrive, stop at the visitors center to get your bearings and to ensure you know where your must-do activities are taking place. Try to slow down, relax and enjoy the haven from rushed, everyday life. It may take a little transition time. When my kids and I volunteered at a living history site, it would take them 30 minutes to an hour to unplug their 21st-century brains. But once they adjusted to their old-fashioned surroundings, they found adventures with the outdoors, animals and crafts the site offered.

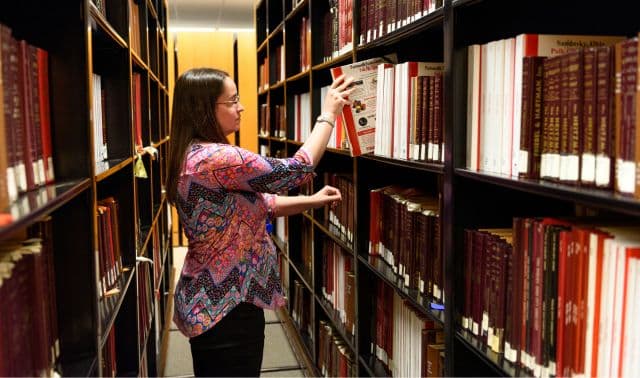

Most living history activities rely on extensive historical research to create a sense of stepping back in time for visitors. Professional actors and trained interpreters dressed in historical clothing use accurate replicas of artifacts and tools to demonstrate activities typical of the time and place, such as cooking, cleaning, handicrafts, songs and games. Interpreters may act as though they’re from the past (first-person interpretation) by assuming real or fictional characters, or they may teach about the past (third-person interpretation). Take advantage of the guide’s knowledge and training by asking your questions about your ancestors’ lives.

Critics point out that museums’ historical authenticity varies depending on the skill and enthusiasm of the interpreter. The same can be said of books, movies and teachers you might turn to for historical insight. Even the most meticulous family historian usually can find a new perspective from a living history actor portraying an ancestral time and place.

During your visit, don’t forget to focus on what you know about your ancestor. Besides participating in activities that apply to your family’s history, try traditional foods and bring home old-fashioned souvenirs. Pick up brochures to save. Take plenty of photos and if you like to write, record your thoughts. Periodically ask youngsters about their favorite part of an activity and what they learned. If you enjoy your visit and you’re able to, make a donation to help others learn about our past.

5. Document your experience.

Living history representations can be great examples of your family’s history and help explain how the lives of your ancestors unfolded. Use the images from your visit to illuminate your family history research. Record new information (such as when that pioneer ancestor might’ve finally seen a successful crop) and research theories, along with the place and date of your visit.

If you had kids or teenagers along, encourage them to create a scrapbook, shadowbox display or video about the event. They may even be able to incorporate materials from the trip into a school project. Perhaps the seeds you’ve planted will grow into a genealogical interest (you can’t force it; all you can do is continue to provide learning opportunities and cross your fingers).

Finally, share your best pictures and stories and video on Facebook, your blog, YouTube or in a photo book. Living history sites are museums without the “don’t touch” signs. They make your ancestors’ names come off the page and turn into living people.

ADVERTISEMENT