Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It’s 1744, and a 7-year-old boy’s life is about to change course. His father, a minister, has just passed away. Now he’s leaving his home in Quincy, Mass., for Boston, where his uncle Thomas — one of the city’s wealthiest merchants — will raise him. As Thomas’ adopted son, he’ll graduate from Harvard at age 17, then inherit his uncle’s business after Thomas’ death in 1764. Five years later, the young man will win a seat in the Massachusetts legislature, and ultimately become one of the most recognizable names in US history as a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

That boy’s identity? John Hancock. And he’s just one of many well-known American adoptees or orphans: Naturalist John James Audubon, author Edgar Allan Poe, singer Ella Fitzgerald and burger baron Dave Thomas are all in Hancock’s company. Even two US Presidents — Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton — were adopted by their stepfathers.

Ever since Hancock’s day, “nontraditional” families have been a traditional part of American society, leaving question marks in many family trees. For genealogists, encountering an adopted or orphaned ancestor might seem like the ultimate brick wall. Sealed records, falsified birth certificates and uncooperative relatives are just a few of the obstacles that could stand in your way. But don’t resign yourself just yet to a blank branch on your pedigree chart. Muster up your creativity, patience and persistence, and adopt these 11 research strategies.

1. Study Adoption History

Before you try to dig up genealogical details, it’s helpful to have a grasp of past adoption practices. Adoption as we know it today is a relatively recent phenomenon. The first adoption law, enacted in Massachusetts, didn’t come about until 1851. Although other states followed suit, legal adoptions remained fairly uncommon as late as 1900.

So what does this mean for your genealogy research? In 18th- and 19th-century America, adoptions were typically informal. “Adoptions frequently took place between relatives or neighbors — it was common for the family or community to step in to care for a child,” says Sandy Mochal Thalmann, a professional genealogist and social worker who, through her research firm Authentic Origins, specializes in helping families unravel adoption mysteries. “Some of these arrangements were never legalized, but came to be known in the family as adoptions.”

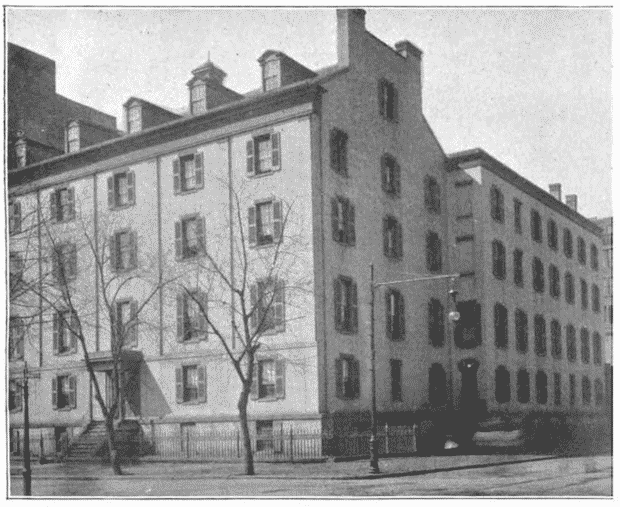

In the 1800s, government and charitable organizations established institutions to care for poor, abused and orphaned children (private facilities were known as orphanages; public ones included poorhouses and almshouses). Between 1820 and 1860, 150 orphanages sprang up across the country; in the decades following the Civil War — which left thousands of children fatherless — the number of orphanages tripled. Don’t let the term orphan mislead you: Many children who lived in or were adopted out of these institutions had at least one living parent.

Wealthy New York socialites formed the first specialized adoption agencies between 1910 and 1930. In response to popular attitudes, especially the stigmas of illegitimacy and infertility, social workers began sealing adoption records in the ’30s through the ’50s. Today, most states have strict statutes governing access to adoption documents.

2. Verify Family Legends With Records

Perhaps you’ve heard family stories about an adopted ancestor. Maybe you have baby photos of all your aunts and uncles but one. Or census records suddenly show Grandma living with a seemingly unrelated family. Whatever triggered your suspicions, how can you find out if they’re true? Don’t jump to conclusions — look for evidence in staple genealogical sources.

Going back to census records, for example, the relationship column (in 1880 and later enumerations) could provide proof: Look for the abbreviation AD, census-taker shorthand for “adopted.”

In his will, great-grandpa may allude to the fact he’s giving an inheritance to “my adopted son,” or “my sister’s daughter whom I’ve raised as my own.” Likewise for deeds. Check the county courthouse for name-change petitions, and don’t overlook criminal proceedings (in case a parent’s crime led to the child’s being orphaned).

Did your ancestor’s case make news? Scour local newspapers’ notices of adoption hearings, as well as the headlines. “I recently found a front-page article in a [1913] small-town Minnesota newspaper detailing a child’s adoption, and the agony his young mother went through,” says Thalmann. The story revealed the names of the child (both pre- and post-adoption), the father who deserted him and the adoptive parents.

Genealogical and historical societies have published some adoption lists in their journals. You can locate relevant articles using the Periodical Source Index (PERSI), available on HeritageQuest Online (free via subscribing libraries). Try searching for a place or person plus the keyword adoption, then click on an article title for details. To get the actual text, request the journal through interlibrary loan or order copies from PERSI’s creator, the Allen County (Ind.) Public Library.

Carefully study home sources such as family papers, photos and letters, too. For informal adoptions, these may be your best (or only) clues. They also could give information that dispels your theory: Does Grandma’s diary explain the absence of Uncle Stan’s baby pics? Perhaps she recorded his birth in the family Bible.

3. Question Your Relatives

Conducting interviews with older family members can prove productive for gleaning information about a relative’s adoption. Though you can’t take an oral history as gospel — after all, people forget details and confuse facts as the years pass by — your kin’s recollections will serve as a foundation for further research.

This can be a difficult topic to broach: Relatives may be reluctant to talk because of the shame historically associated with illegitimate births. “Some families have closed ranks around the secret,” says Thalmann, and would consider it a betrayal to tell that secret — even if the people involved are no longer alive.

So ease into the subject, and approach it with an attitude of openness and acceptance. “The atmosphere of the interview is more important than the questions,” says Thalmann. Tell your interviewee how you’ll use the information, and let him or her know you’ll honor the privacy of living people (including him or her).

Thalmann recommends interviewing multiple family members, including kin further removed from the adoption. “Grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins (or their descendants) may have less apprehension about sharing [their knowledge],” she says. Plus, they’ll give you additional information you can use for comparison and corroboration.

4. Obtain Birth Records

Naturally, you’ll want to see if you can get your hands on your relative’s birth records, since they provide information about a baby’s parents. The good news: “Sealed record laws were not retroactive,” says Thalmann, so if your adopted ancestor was born before her state enacted such restrictions, you’ll have the same access to her birth records as any other forebear’s.

Adoptees may have two birth certificates: an original record with the birth parents and child’s birth name, and an amended, or “delayed,” certificate noting the adoptive parents and the child’s new name.

Keep in mind that the existence of a delayed birth certificate doesn’t necessarily signal an adoption. Government record-keepers issued them for many other reasons; in most states, for example, people who were born before the start of statewide vital-record-keeping could file for delayed birth certificates in order to apply for Social Security or passports.

Now for the bad news: There might not be a certificate — original or delayed — for you to get. “Some parents chose not to record the birth due to the shame of a child being born out of wedlock,” says Thalmann. Further, many states didn’t require vital statistics until the early 1900s. So a lack of documentation could be your real obstacle. See if the county’s records predate the state mandate, and search for alternative sources such as baptisms, family Bibles and newspaper announcements.

5. Arrive on Time

Be sure you’re looking for evidence in the right time frame. Formal adoptions didn’t always occur immediately after a child was taken in. Adoptive parents sometimes waited until they were certain the child would mesh well with the family, especially if an inheritance was involved.

My great-uncle Richard Reese, who was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1890, was one of those delayed adoptions. Richard’s father abandoned his mother and eight siblings — including my grandmother Emily — in 1895. Richard and Emily subsequently ended up in Brooklyn’s Home for Destitute Children, part of the Brooklyn Industrial School Association.

In 1903, the home sent Richard out “on trial” to William and Hannah MacKay of Brooklyn. Though he stayed with the family and even took their last name, they didn’t officially adopt him until 1911, when he was 21. I found the date in the index to adoption records on file at Manhattan’s municipal archives, but unfortunately, I couldn’t access the actual court documents — New York has one of the strictest sealed records laws in the country.

6. Make Internet Connections

The Internet makes it easier than ever to connect with distant cousins and fellow researchers who may hold clues to your adopted or orphaned ancestor’s parentage. That’s how I learned more about my great-uncle. After obtaining a Social Security application and census records for a man I suspected to be Richard, I posted queries on genealogy message boards. In a few months, one of Richard’s adoptive cousins e-mailed me. Much to my delight, she shared memories of Richard and sent me several original photos of him.

Try making your own connections online. A number of message boards at Ancestry.com cover adoption, orphans and orphanages. Don’t just post messages — you can get good tips and advice by searching or browsing old conversation “threads.” Ditto for e-mail lists: Go to RootsWeb for a lengthy compilation, including some that relate to adoptions and orphanages in particular states.

7. Go to Court

So you’ve determined your ancestor’s adoption took place through official channels. Your first course of action should be to pinpoint exactly where it happened. You’ll find a handy list of 21 states’ adoption jurisdictions — that is, which courts had purview and when they got it — in the court records chapter of The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy (Ancestry). But generally speaking, the county courthouse usually handled adoptions. So if you know the county where the adoptive parents resided at the time of the adoption, start with the probate court there. Juvenile courts weren’t established till the 20th century; before that, some jurisdictions had orphans courts.

Formal adoption records typically contain the prospective parents’ adoption petition (which gives their identities, as well as the birth parents’, if known) and the court’s final order, which may detail the circumstances leading to the adoption and give the child’s birth name. If the birth parents objected to the petition, the file might contain a transcript of a hearing.

Like adoptees’ birth records, pre-1930 adoption files are open in most states. The problem? “Formal adoption records are rare prior to the 20th century, and accessing them is difficult,” says Thalmann. “Many records have been lost in the zeal for keeping them private.”

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ FamilySearch Library (FSL) has microfilmed court records from many US locales; do a place search of the online catalog to see what’s available for your ancestor’s county. But there’s a good chance you’ll need to research at the courthouse. “Don’t begin the conversation with a records clerk with ‘I’m searching for an adoption,’” Thalmann advises, and know the record laws. If a clerk refuses you access to documents you should be able to view, talk to his superior. “Even if access is legal under the statutes of that jurisdiction, many record holders interpret the law as sealing adoption records permanently or forever.”

8. Consider Alternatives

Remember our tip about brushing up on historical context? If you can’t find evidence of an ancestor’s adoption, reconsider your assumptions. As we’ve noted, legal adoption didn’t come about until the mid-19th century. But perhaps your relative’s fate was formalized in another way.

Beginning in the Colonial era, for example, American courts carried on the English tradition of apprenticing orphaned children to local craftsmen or organizations so they could learn a trade. These apprenticeships (sometimes called indentures) typically lasted until the orphan reached age 18 to 21; the practice continued into the 19th century. That’s what happened to my great-grandfather William Henry Fross: When his dad died in 1847, 10-year-old William and his younger siblings became apprentices in the Shaker community of Waterlivet, N.Y. After William’s obituary tipped me off to his fate, I got his records from Waterlivet — which revealed the details of his apprenticeship, including that he learned carpentry and broom making.

Apprenticeship agreements usually tell how long the indenture would last, what trade the child would learn and — most important — who his parents or guardians were. Start by looking for published compilations such as Ancestry’s Apprentices of Virginia 1623-1800 by Harold B. Gill Jr. and Apprentices of Connecticut 1637-1900 by Kathy Ritter (both are out of print but available through libraries). To find the actual records, look in local, county and state courts, or check state archives and historical societies for microfilmed copies.

Apprenticeships were just one form of legal guardianship — other custody situations played out in court, too. In particular, courts often appointed guardians to manage inheritances left to orphaned kids until they reached adulthood. Even family matters could become legal matters: If a child’s father died, mother could remain the official guardian if the court deemed her capable of supporting the child. Paperwork from the proceedings varies, but it usually reveals the birth parents’ identities.

Since the cases involved the death (and estate) of a parent, guardianship proceedings typically occurred in probate court — the records might even be part of a probate file. Besides at the FSL (look in the catalog under the Guardianship and Probate headings), you may find older guardianships in state and local repositories, or get microfilmed records through interlibrary loan.

9. Check Into Institutions

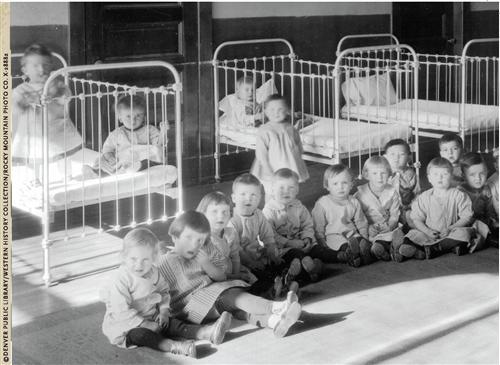

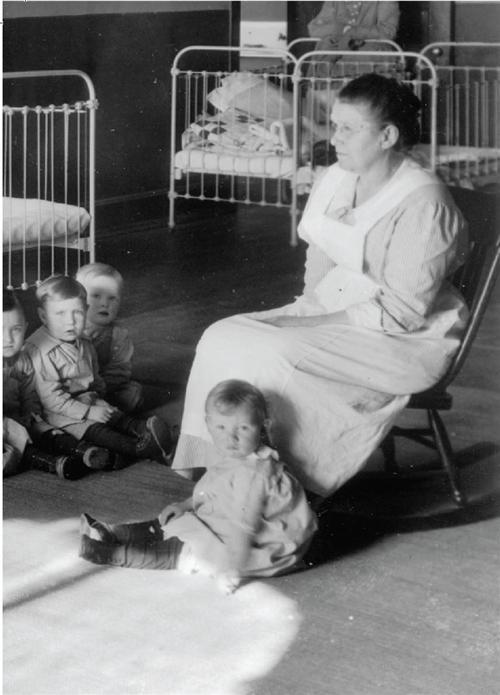

Did your ancestor end up in an orphanage? It might’ve been called a children’s home, almshouse, infirmary or asylum, but these institutions served the same purpose: taking in kids who were orphaned, abandoned, or whose parents couldn’t provide for them.

Aside from local almshouses boarding kids too young to be apprenticed, relatively few of these institutions existed before the mid-19th century wave of Civil War orphans. The number of needy children continued to climb as America coped with the effects of industrialization and mass immigration. By 1910, more than 100,000 US youths resided in institutions.

US census records are a good starting place for tracing them: Institutions were counted just like other households. So if your ancestor lived in an orphanage, he’d show up as a resident. (Hint: If you subscribe to Ancestry.com — or your library does — search its database on the keywords orphan and inmate.) In 1880, the government also took supplemental schedules of “defective, dependent and delinquent classes,” including lists for homeless children and “paupers and indigent.” Check the FSL catalog for microfilm, and see Kathleen W. Hinckley’s Your Guide to the Federal Census (Betterway Books) for a chart showing where the original records are.

If you can’t pinpoint your relative’s institution in the census, you’ll need to research children’s homes in his area. You can search the web and comb city directories to find orphanages and children’s homes. Learn the home’s genealogy, too: After your kin left, did it change names or owners, move to a new location or shut down entirely?

Your goal, of course, is to get records of your ancestor’s stay. Generally, admission documents give the child’s name, case number, age or birth date and birthplace; the parents’ names and birthplaces; and details about the next of kin. But the files’ full contents and whereabouts depend on who ran the institution — and whether it’s still in business. Government-run facilities have probably turned over their historical records to the state archives or social services department. Records of orphanages run by religious groups are often in the denomination’s archives. Currently operating private homes still might hold their old paperwork, so check there first.

Now-defunct facilities’ records could be in a nearby historical or genealogical society, state repository, local or university library, or even with institution officials’ families. For help, try consulting the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections under the institution’s name, its location and its officials’ names. You’ll find volumes since 1986 on the Internet; earlier editions are in print at large libraries and on microfilm.

With few exceptions — notably, the Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Children’s Home, Nevada Orphans Home (1870 to 1920) and Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum (1878 to 1969) — institutional records aren’t online.

10. Try the Train

In the mid-1800s, the Children’s Aid Society of New York City began a push for “placing out”: moving kids from orphanages into “stable” homes, where child advocates believed youngsters would be better off. So the society — led by founder Charles Loring Brace — shipped out orphans and abandoned children on “orphan trains.” Other charitable organizations, including the New York Foundling Hospital, the New York Juvenile Asylum and the New England Home for Little Wanderers, soon followed Brace’s lead. Between 1854 and 1930, 200,000 East Coast kids were loaded onto trains to the rural Midwest where they could be adopted by anyone.

Today, orphan train riders’ descendants number 2 million — and resources for tracking those forebears are correspondingly abundant. The Children’s Aid Society and other organizations have retained records of the children they placed out. You’ll also find records in historical societies, university libraries and state child-welfare agencies.

Also search local newspapers, too: Articles often announced the arrival of orphan trains, even listing the names of children and their foster parents.

11. Take a Detour

Above all, don’t give up. By putting these 11 tactics into practice, you can reclaim the orphan branches of your family tree.

When you can’t find your adopted ancestor’s origins, try the same “back door” approach you’d use for other elusive forebears: Look for her by studying her relatives. Emily Anne Croom, author of Unpuzzling Your Past, 4th edition (Betterway Books), calls this “cluster genealogy.” (Read Croom’s guide to cluster genealogy in the 2006 Genealogy Guidebook, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine.)

From the February 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated March 2023.