My mom’s voice was strained. “There’s something I need to tell you, and it’s going to rock your world.” I was 45 years old, still grieving my dad’s death the previous year. Mom explained that in the early 1970s, my dad learned he was incapable of fathering children. Heartbroken, they saw a physician who suggested using a sperm donor.

And there it was—the truth. My dad, whom I loved and missed more than seemed possible, was not my biological father.

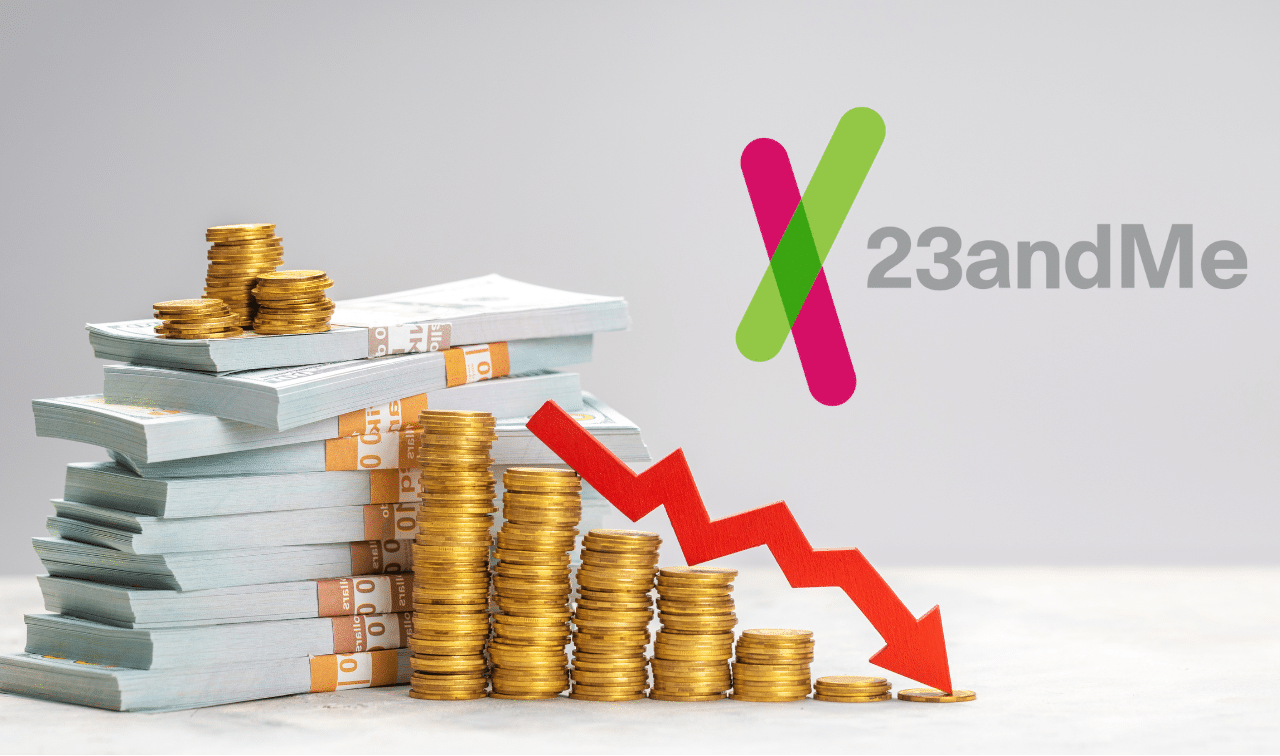

With recent developments in DNA testing, many people are discovering that their paternity differs from what they believed. They might find that they were adopted, conceived through a sperm donor or conceived naturally by a different father. The revelation is fraught with emotion, both for us learning the news and for our parents, who may never have intended for us to know.

Thankfully, you can navigate the overwhelming emotions and decisions that follow such life-changing news. Here are six steps to working through a big revelation about your genetic family, based on my experience as both a doctor and the child of a sperm donor.

Step 1: Don’t Seek Answers Right Away

My first impulse was to find my sperm donor’s identity through DNA analysis. There was an entire piece of my existence unknown to me, and I wanted answers! But my husband suggested I wait a few months, giving me time to process my emotions and make thoughtful choices about how I’d seek out that information.

Some people discover accidentally through DNA testing that their paternity is different than they believed, rather than being told by a loved one. If that is your experience, you might already know your biological family’s identity. If you can, refrain from contacting them until your emotions have stabilized.

Step 2: Process Your Emotions, and Seek Counsel

While not everyone faced with a discovery like this needs formal counseling, I strongly recommend it. As a family doctor, I’ve seen how unprocessed emotions can cause problems later in life. Sharing your feelings with a counselor or a wise and trusted friend or family member can help you work through the complex web of emotions you’re feeling.

For weeks, I could hardly eat or sleep. From anger to excitement to a deep sense of grief, my emotions fluctuated. Attending several sessions with a licensed counselor proved invaluable in working through my feelings.

Disappointment was my biggest struggle. I looked up to my dad more than words could express. I had patterned my life and values after his. I was devastated to realize he wasn’t biologically a part of me. I felt like I’d lost him all over again.

My counselor assured me that my dad will always be a part of me. Decades of research show that environmental cues—not just genetic information—affect the development of brain structure in early childhood. Though we didn’t share genes, my dad was a biological part of me, as his modeled behavior influenced the physical connection of neurons in my brain. That brought me great comfort.

Step 3: Decide Who You Will Tell

Initially, I shared my discovery only with my husband and a few close friends. I worried people might take the news flippantly, not understanding its significance to me. My parents had kept the information a secret themselves, and I wanted to respect that.

The decision whom to tell is complex because it can affect both you and your family members. Consider your parents’ desires if they are still living. Give them time to process their feelings and attempt to find a common ground about whom to tell.

If you have children, consider when you’ll tell them, depending on their ages and your comfort level. Remember that with DNA testing and the wealth of information available online, they’ll likely find out someday. They may resent the information less if they hear it from you and are given the proper space to process it themselves.

Step 4: Make Peace in Your Own Way

At first, I felt hurt that my parents hadn’t told me the truth. My mom explained that they never told anyone. At the time of my conception, use of a sperm donor was unusual and carried a stigma of shame. Mom and Dad were concerned their families and friends wouldn’t understand or accept their decision.

Most importantly, they saw me as their daughter and wanted everyone, including me, to view me as such. Over time, through talks with my mom, I began to understand why they made that decision. Mom and I came to a place of loving understanding.

It was harder for me to make peace with my late dad because we couldn’t have a conversation. I wanted to tell him how much I loved him and assure him this news didn’t affect my view of him in any way. So one day, with tears streaming down my face, I spoke out loud, expressing everything I wanted him to know.

You might also feel angry or betrayed that your parents or other loved ones didn’t share the truth with you. Try to understand their point of view, considering cultural context. Secrecy is common in these situations, and was especially so in the past.

Making peace with them—at least in your own heart—is important. If you’re able, you could have a conversation with them, or (particularly if they’ve passed on) write a letter or journal about your feelings.

Step 5: Research the Identity of Your Genetic Family

Exciting questions flooded my mind soon after finding out the news. Differences between me and my family that I’d often wondered about began to fall into place like missing puzzle pieces. Could the shape of my nose, my personality and even my career choice have been influenced by my biological father?

At the same time, I felt guilt about pursuing answers. Was I betraying the memory of my dad by seeking out my genetic family? Other family members assured me that my dad would want me to find answers that could benefit me and my children. Over time, I found peace about beginning the search.

Consider both the positive and negative outcomes that could result from learning the identity of your genetic family:

- Positive: Discovering your ancestry can have both emotional and medical benefits. Your genetic family tree might be publicly accessible online, and simple searches for obituaries could reveal your recent ancestors’ ages and causes of death. The latter might suggest diseases linked to your genetic makeup. And if you choose to contact your biological relatives directly, they might share detailed family medical history.

- Negative: Negative outcomes mainly consist of the emotional repercussions of your discoveries. You don’t know what you’ll learn—you could find disturbing information (such as evidence of a criminal record or dangerous genetic disease), or maybe no information at all. Be prepared to work through these types of disappointment.

Step 6: Consider Contacting Your Genetic Family

If you do find matches, you’ll next need to decide whether to contact them—and how you will respond if they contact you. (Even if you decide not to find your genetic family, DNA testing has made it easier for relatives to find each other.)

Consider the pros and cons of contact

As when deciding whether to research your genetic family, you should weigh the possible positive and negative outcomes of contacting newly found relatives. You could gain valuable information about your lineage and family stories, plus medical history and information such as where your eye color comes from or why you have certain interests. Your family might even agree to some kind of relationship, or one could develop over time.

However, your genetic family could have a drastically different lifestyle or set of values from you. They might respond curtly or in an unkind way (or maybe even not at all). Try not to take that personally—they don’t even know you, and their choice in answering or ignoring your message depends entirely on them and their circumstances. It has nothing to do with you or your worth as a person.

I decided to take a DNA test to learn more about my genetic family. When I received my results, I was thrilled to see matches not only with my sperm donor, but also three half-siblings. With this information, I learned more from internet searches and accessing public family trees online.

Contacting collateral relatives

I wasn’t ready to contact my donor directly. But I did reach out through the DNA matching system to my half-siblings. My half-sister replied immediately and with enthusiasm. Her sperm donor heritage had recently surprised her, revealed unwittingly by DNA testing. We supported each other emotionally as we shared the discovery.

About 18 months later, a second half-sister contacted me, questioning why she had matched with us. As her parents were deceased, it fell to me to gently explain the situation to her. I’ve since developed close relationships with both sisters, enriching my life greatly. Our children are near the same ages and consider each other cousins.

Since then, I’ve been contacted by two half-brothers and two additional half-sisters, one of whom is my donor’s natural daughter. Some relationships have grown closer than others, but each of them has brought me joy.

Deciding what to say

At first, I felt uneasy about messaging my donor. I worried he may not answer my message, or that his response might somehow hurt my feelings. These emotions are valid and normal, and it can help to talk about them with a trusted confidante.

My mom advised me to consider his advanced age and contact him while he was still living. With time, my concern about missing the opportunity outweighed any fear of rejection. After a few months, I messaged him, explaining that our DNA match indicated he was likely my donor.

I thanked him for the amazing gift he gave to my parents (who wanted so much to have a child) and to me (as I wouldn’t exist without him). I asked if he would share family medical history that could affect me and my children. He may not have expected any donor children to identify him, and I assured him I would respect any level of privacy he requested. I expressed my openness to continuing contact and my interest in learning more about him and about my heritage if he felt comfortable sharing.

Moving forward

His reply was friendly, expressing interest in continued email correspondence. We shared information gradually over time. He sent family medical history and a family tree tracing our heritage to passengers on the Mayflower. He sent photos of his family (including his parents and other ancestors) and shared stories from their past and from his own life. The resemblance fascinated me, especially our noses and face shapes.

I shared stories from my own life and told him about my children’s temperaments and hobbies. I sent photos of myself and my family. He wrote about his own personality and interests, which turned out to be similar to mine. Although we haven’t met in person, I feel that I know him well.

Nothing can compete with my deep love for my dad who raised me, but I’m delighted to know the man who contributed to my genetic makeup. I consider the relationship one of my most cherished.

My mom was right that Saturday when she predicted that the news she shared would rock my world. It was a life-changing event, shifting my perception of my identity and requiring time to process. There were difficult questions and emotions to face.

But it launched an intriguing adventure resulting in new knowledge of myself and priceless relationships. Nothing can match the unique, profound love I have for the family of my childhood. But I’ve found my heart is big enough for all my kin.

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2024 issue of Family Tree Magazine.