Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

If you’re a genealogist, you’ve probably devoted considerable time to discovering your ancestors’ origins. Just knowing the place they came from, however, is rarely enough. Genealogists also want to know how their ancestors lived, what they did for work, what they wore and ate, and what their homes looked like. What you need is a resource that’s not only rich in genealogical information, but also shares the richness of your ancestors’ culture.

And if a relative’s specific place of origin yet proves elusive, learning the history of that heritage group may offer another research pathway, suggesting new records to try or offering clues about the lives of his countrymen.

Heritage or cultural centers and museums situated throughout the country—usually in places where people of a particular heritage settled together—cover just about every ethnicity and cultural group woven into the fabric of America. Whether your ancestors hail from Germany, India, Ireland, Japan, Sweden, Syria, Ghana, Mexico or anywhere else, there’s probably a museum that provides historical materials and a glimpse of that culture’s customs, history and people.

Some such centers serve both as history museum and research destination, with manuscript collections, foreign-language newspapers, photographs, maps, local histories and more. They may offer genealogy workshops or history classes. “Every month, we have a genealogy session that covers what our library has available and how to get started finding Irish relatives,” says Kathy O’Neill, a staff member of the Irish American Heritage Center in Chicago.

Those who work and volunteer at heritage centers often share the culture or have intense interest in it. Karile Vaitkute, a genealogist at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, reads Russian and Polish and understands the name change patterns of immigrants from these areas.

Okage Sama De, the title of an exhibit at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i, translates to “I am what I am because of you.” That’s the crux of why heritage museums are important: Exploring one rewards you with a better understanding of who your ancestors were—and thus, how you came to be who you are.

In this article, we highlight 11 of the best heritage museums in the United States, chosen for their genealogist-friendly research libraries, exhibits, tours, classes and community events. Use this guide as a springboard to similar organizations covering your family’s heritage. Note that previews of each destination were accurate as of this article’s original publication in 2017 but may have changed—contact each museum to verify details.

That’s the crux of why heritage museums are important: Exploring one rewards you with a better understanding of who your ancestors were—and thus, how you came to be who you are.

Planning for a Heritage Museum Trip

Planning to visit the research library at a heritage museum? Get the most out of your trip by following these tips:

- Scan the museum’s website to understand the types of materials its library holds. The collection will probably be helpful no matter where your ancestors lived, but you’ll want to know if, for instance, it focuses on immigrants who settled where the museum is located. If possible, search the online catalog from home to identify materials you want to use.

- Call ahead to verify hours and any fees (including acceptable forms of payment), ask about special services such as translation, and make an appointment with a research center staff member if needed.

- Find out about research room rules. For example, you may need to apply for a researcher ID or use only pencils.

- School yourself in the basics of history and genealogy research for the heritage group of interest by reading Family Tree Magazine guides. That way, you won’t have to spend as much of your visit getting up to speed.

- Bring a pedigree chart with as much information as you know, including relatives’ names and birth and death dates and places. Summarize what you’ve learned about the people who immigrated, even if all you have are stories. “If your family talks about your great-grandfather who always went to the river to catch fish, that can be a clue to a geographic area,” says Karile Vaitikute of the Balzekas Museum.

- Bring good-quality images: full-color copies or high-resolution digital images of any records needing translation.

- Consider becoming a museum member or making a donation, especially if the research center charges minimal fees. After your visit, send a thank-you note to acknowledge any special help you received.

American Italian Cultural Center

New Orleans

Immigrants from Sicily, who flooded New Orleans in the late 1800s, gave the Big Easy its famous muffuletta sandwich. You can still steep in your family’s Italian heritage here, in addition to starting your genealogy search. Sal Serio, the center’s genealogist, conducts family history classes for Italians and those of other nationalities.

Genealogists researching Italian roots can access special collections at the library, including books, magazines and Italian-language newspapers. “We’re especially strong on vertical files,” Serio says. “Those files are packed with information about businesses and especially benevolent societies which are prolific in this part of the country.”

If you can’t make a class, make an appointment. Experts will help guide you to the right sources, and can help with translation. The center also offers Italian language courses for those who want to translate on their own. Museum exhibits focus on the stories of Italian immigrants to the Southeast, and Italians in jazz and sports. Don’t miss the nearby outdoor Piazza d’Italia, built by the city to honor its Italian heritage, where you can play bocce ball, listen to a concert, watch traditional flag-throwers and attend wine tastings.

Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture

Chicago

Home to the world’s largest Lithuanian community outside Lithuania, Chicago also hosts the Western Hemisphere’s only museum focused on Lithuanians. The genealogy department here holds newspapers, books, obituaries, annals, maps and other documents in an collection that spans most of Lithuania’s turbulent history, from the 13th century to 1940.

Although you won’t be able to research the collection yourself, staff provide in-depth consultation services to museum members (memberships start at just $35 per year). Nonmembers also can take advantage of fee-based services including translation of old, handwritten documents. Spellings of Lithuanian names and places can vary widely, as can languages used in records. Pre-WWI documents, for example, are usually written in Russia’s Cyrillic script. Records also may be in Latin or Polish.

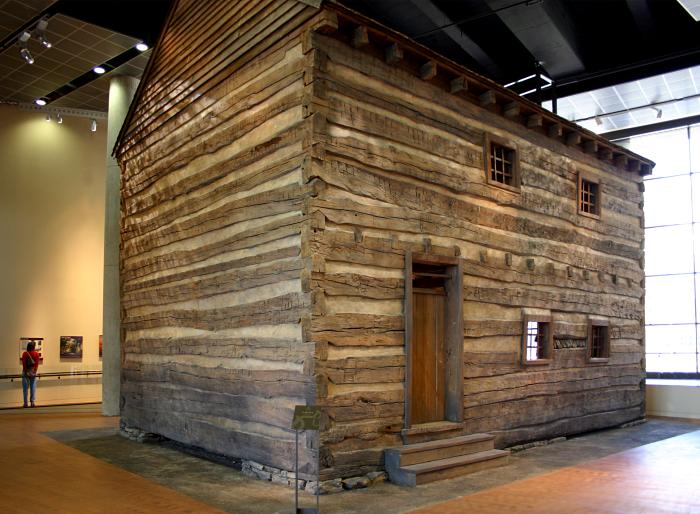

You can get to know the culture of your ancestors in the museum, says Karile Vaitikute, genealogy department director. “There are exhibits and a film that describe Lithuanian history, national costumes, Lithuanian art, agricultural items and even a small house,” she says. The museum also provides workshops and guided travel opportunities.

Cherokee Heritage Center

Tahlequah, Okla.

For those who want to explore Cherokee culture, there may be no better place to do so. Your admission to the Cherokee Heritage Center allows you access to the Trail of Tears exhibit, Diligwa (a 1710 Cherokee village), Adam’s Corner (an 1890s rural Oklahoma village) and Cherokee Family Research Center. Note that, as of April 2024, the center is temporarily closed to the public.

Most visitors are new to genealogy. “They’re here primarily because they learned from a family story or legend that one of their ancestors is Cherokee,” says Gene Norris, the center’s genealogist. He recommends starting your research with three federally conducted and compiled rolls covering the Cherokee: the Dawes Final Roll, the Guion Miller Roll and the Baker Roll. (The center’s website offers tips on getting started, and you can consult Family Tree‘s American Indian genealogy guides.)

The library provides access to a variety of websites and records, including government and private documents, photographs, posters, maps, architectural drawings, books, manuscripts and articles focusing on Cherokee history and culture.

Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration

New York City

Ellis Island’s immigration museum has expanded its goal to tell the stories of American arrivals before, during, and after the era when Ellis Island processed immigrants (1892 to 1954). The Peopling of America Center, opened in 2015, shares the migration history of American Indians, slaves transported against their will, and Colonial- and Victorian-era immigrants.

The island’s outdoor American Immigrant Wall of Honor is inscribed with more than 700,000 names of immigrants through all ports. “The wall is the only place in America to honor family heritage at a national monument,” says Stephen Briganti, president of the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation.

If your ancestors did come through Ellis Island, you can walk in their footsteps at the immigration museum, view the renowned Great Hall, and follow an audio tour through the immigrant experience as if you were a new arrival.

Since Ellis Island opened as a museum, a centerpiece has been the American Family Immigration History Center archive of passenger lists. Now numbering 51 million names of immigrants all the way up to 1954, the database is searchable both on-site and online; search results link to images of original manifests showing the immigrant’s name, age, last place of residence and more. You also can view images of ships that transported immigrants—maybe even your ancestor’s.

Historic Huguenot Street

New Paltz, NY

Anyone researching families from Europe’s “Low Countries” of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg should check out the research library at Historic Huguenot Street. Huguenots were Protestants largely from France, who fled their homelands to escape religious persecution. In the United States, many Huguenots settled in New York’s Hudson Valley, South Carolina and elsewhere along the East Coast. Their descendants include George Washington, the grandson of a Huguenot.

You don’t have to have Huguenots in your background, though, to appreciate this 10-acre museum. Start at the Visitor Center, then visit any of the historic stone houses, a reconstructed 1717 church, a burial ground dating to the earliest settlers, archaeological sites and more. Tours are available May through October. If you’re a Huguenot descendant, celebrate your ancestry at the annual Gathering, which includes history workshops that may open a door to your family tree.

“Historic Huguenot Street holds genealogies of the New Paltz patentees and associated families, transcriptions of church records, surname folders that include family trees, plus the archive of items such as letters, family Bibles, and estate records,” says spokesperson Kaitlin Gallucci. You can access the research library on-site by appointment or send a research inquiry.

Irish American Heritage Center

Chicago

A city that dyes its river green each St. Patrick’s Day is a fitting home for the country’s largest Irish cultural center. Nestled on Chicago’s northwest side, the Irish American Cultural Center houses a museum (open for tours by appointment) with artifacts including exquisite Irish lace, an art gallery, the Fifth Province pub, a theater, classrooms and a research library. “This is the place to find out where you’re from,” says spokesperson Kathy O’Neill.

Library resources include 25,000 books on Irish history and literature, newspapers, access to online databases, and other material. A limited-access archives section preserves documents, records and other rare and historic items. Family history classes take place once a month, or you can make an appointment with a staff researcher. Other classes cover Irish language, history and music.

To celebrate your Irish heritage, check out the center’s folk concerts, traditional céilí dances, festivals and storytelling events.

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i

Honolulu, Hawai’i

Those tracing Japanese roots, and especially Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, will find a valuable resource here. “The center’s historical Okaga Sama De exhibit tells the story of Japanese immigration to Hawaii, from 1860 to statehood and beyond,” says Derrick Iwata, education and cultural specialist.

Visitors can also tour the Honouliuli Education Center, which focuses on Japanese internment during World War II. Experience present-day Japanese culture during one of the center’s festivals, including a New Year’s Ohana (Family) Festival on the second Sunday in January. Or come for the classes on martial arts and the Japanese tea ceremony (called chado, or the Way of Tea).

The Japanese Cultural Center’s Tokioka Heritage Resource Center offers a wealth of material related to Japanese-American history, art and culture in Hawaii and on the mainland. “Our library and archives has an assortment books and oral histories, as well as a number of directories which list Japanese residents in Hawaii,” says center manager Marcia Kemble. Access the online library catalog. Volunteers and staff can provide fee-based services such as translation, Japanese name consultation, and genealogical assistance—including help obtaining a family registry record, or koseki tohon, from Japan. (Note that the center is not taking new translation requests as of April 2024.)

Tip: Cultural museums are inspiring and informative destinations even when they don’t represent your ancestry. “They represent diversity and the power of multi-ethnic communities,” says Audrey Kaneko, program director at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i.

Museum of Jewish Heritage

New York City

“In the case of Jewish genealogy, where so many records were lost and lives disrupted, an institution like the Museum of Jewish Heritage provides a crucial narrative,” says Michael Glickman, president and CEO of New York City’s Museum of Jewish Heritage. Its core exhibition uses first-person histories, photos, video and personal objects to explain pre-WWII Jewish history and tradition, European Jews’ confrontation with the hatred and violence of the Holocaust, and Jewish communities today. You can view a selection of photos and documents from its collection. The outdoor Garden of Stones serves as a memorial to those lost in the Holocaust.

This museum’s “research library” is online at its partner website, JewishGen. JewishGen hosts discussion groups with more than 30,000 participants and holds millions of Jewish records, including Holocaust records, a burial registry and the Communities Database. “Say your grandfather came from a town called Ostroleka,” Glickman says. “You might find six towns with the same name. How would you know which is the town your grandfather was referring to?” The database lists 6,000 Jewish communities, with their political jurisdictions and name variants over time.

National Hispanic Cultural Center

Albuquerque, N.M.

Archivist Anna Uremovich calls this center a “full saturation of the Hispanic culture.” Its art museum features a 4,000-square-foot buon fresco depicting thousands of years of Hispanic history, works from Spanish artists around the world, and classes and other events.

Its research library and archives is a destination for family historians with deep Southwest roots, holding Spanish census records, land grants, and an impressive 90-volume set of Enciclopedia Heraldica Genealacia Hispano-Americana and the 15-volume Diccionario Hispanoamericano de Heraldica Onamastica y Genealogia. These books include more than 15,000 names from Spanish and Spanish-American families.

You can search the research library catalog. Tracing family history is part of the Hispanic culture, Uremovich explains, and suggests researching Catholic parish records to learn birth, marriage and burial details, and sometimes, names of other relatives.

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

Cincinnati

If you’re searching for your African American roots, head for the John Parker Library on the fourth floor of this inspirational museum. (Admission isn’t required if you’re just visiting the library.) The library hosts a FamilySearch Center, where you can use databases, microfilm and other resources from FamilySearch. You can call ahead to schedule an appointment with an on-site genealogist. “We help between 60 to 120 patrons a month start or continue to research their family trees,” says marketing director Jamie Glavic. He recommends first completing as much of a pedigree chart as you can.

The Freedom Center museum can help you understand the experiences of your enslaved ancestors—who they were, how they were transported to America, and how they lived and worked here. Step inside a slave pen built in the early 1800s on a Kentucky farm, and follow in the footsteps of Underground Railroad passengers and conductors whose actions resisted slavery.

You also can watch a short film, narrated in part by Oprah Winfrey, that describes the work of early abolitionists, intent on ending slavery. “Genealogists should seek out cultural museums to gain a greater understanding of the diversity of the human experience. Each history, each story is unique,” Glavic says. “Cultural museums can provide perspective, details, and can lead to additional resources that assist with family research.”

Swedish American Museum

Chicago

Step inside this museum in the heart of Chicago’s “Little Sweden,” and you walk in the footsteps of Swedish immigrants, from preparing to leave their homeland to building new communities in America. View artifacts including steamship tickets, passports, folk crafts and household items brought from Sweden. A children’s museum allows kids to do chores in a stuga (farmhouse) and board a 20-foot “steamship.”

The center’s Genealogy Society is “the only Chicago-area center that focuses on Swedish research,” says volunteer Vereen Nordstrom. It holds Swedish censuses, immigration and burial records; provides access to church records on the Swedish subscription website ArkivDigital; and hosts genealogy classes. You can make an appointment to work with volunteers, or send a research request.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.