Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Since the early 17th century, when French colonists arrived on the shores of the St. Lawrence River to build the colony of New France, Canada has become the destination of millions of migrants seeking a new life in a new land. And it still is: Every year, more than 200,000 new immigrants arrive in Canada.

Americans may be able to count Canada among their ancestral homelands without knowing it: By the late 1840s, more than 20,000 Canadians (including new immigrants) moved to the United States each year. In the late 1800s, when the United States began implementing stringent entry requirements for some groups of people, many immigrants entered Canada and later traveled south as a way around the new requirements. Americans migrated to Canada for land in the Prairie Provinces, especially as land made available through the US Homestead Act became picked over. Those living near the countries’ border might cross back and forth for jobs and visits with family.

Perhaps you have ancestors who immigrated to, lived in or travelled through Canada. Make the best of your research time by taking advantage of our list of eleven essential resources for Canadian genealogy.

1. Canadian Censuses

Canadian census records are a relatively easy-to-find record group online. A national census was taken every 10 years starting in 1851 (records are available through 1931), and various provincial and other censuses date from as early as 1666. Some websites such as Ancestry.com or its sister site Ancestry.ca require you to have a subscription to search record indexes and view digitized images. (You can search Ancestry Library Edition for free at many public libraries and at FamilySearch Centers.)

But my favorite place to find ancestors in Canadian census records is on the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) website. The LAC site offers free digitized images of Canadian census records from 1825 through 1931.

Start by clicking on Census Records under Most Requested > Collection. The Census Records page provides background information, plus a link to the central Census Search portal. The site has separate articles based on historical era: Pre-Confederation (1825–1867), Dominion of Canada (1871–1931), and Prairie Provinces (1820–1926).

Use these resources to learn which provinces and territories were included in the census, how the census information was collected, what information was collected, what abbreviations were commonly used, what different schedules were used, and what schedules have survived. The 1881 census, for example, had eight schedules but only one, the population schedule, has been preserved. A listing of the names of the districts and sub-districts used in the 1881 census is included, as well as search help.

Other places to find indexed data from Canadian censuses include FamilySearch and Automated Genealogy.

2. Passenger Lists, Immigration Records and Border Entry Records

There are no comprehensive passenger lists of immigrants arriving in Canada before 1865. From 1865 onward, official records of immigration to Canada include passenger lists and, for those arriving overland, border entry records. From 1919 to 1924, immigration officials recorded passenger information on individual forms (called Form 30 for border entries and Form 30A for ocean arrivals) instead of passenger lists and border entry lists. In 1925, officials returned to the large-sheet passenger lists and border entry lists.

Ancestry.com and Ancestry.ca have searchable, digitized passenger lists of ships arriving at various Canadian ports, as well as some eastern US ports. The records in the collection “Canada, Arriving Passenger Lists, 1865–1935” cover the ports of Quebec City and Montreal, Quebec; Halifax and North Sydney, Nova Scotia; Saint John, New Brunswick; Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia; and eastern US ports including New York.

The passengers’ names recorded in these lists include immigrants, visitors to Canada, returning Canadian citizens and individuals in transit to the United States. The amount of information recorded depended on the forms used; as with US records, lists from later years usually recorded more details.

Another passenger lists collection on Ancestry.com and Ancestry.ca is “Canada, Ocean Arrivals (Form 30A), 1919–1924.” Details recorded include the name of ship, port of departure, date of arrival, port of arrival, name of passenger, age, gender, place of birth, marital status, present occupation, intended occupation, citizenship, religion, object in going to Canada, whether intended to live permanently in Canada, name of nearest relative in country from which the passenger came. The front and back side of the forms were originally microfilmed. When viewing an image for your individual of interest, use the arrows to view both sides of the form.

Our ancestors crossed the Canadian-US border for all kinds of reasons, including immigration, employment, visiting family and friends, vacation and shopping. Border-crossing records are an essential resource for anyone who had ancestors in Canada or the United States. Even if you think your ancestor never crossed the border, I encourage you to check these records anyway. You never know what you may find.

Canada began recording names of immigrants entering from the United States in April 1908. Immigrants arriving in non-port cities or when port offices were closed were not likely registered. Returning citizens weren’t recorded, and if one parent in a family was Canadian-born, the whole family was considered to be returning citizens and not immigrants.

Details on border entry records vary depending on the year and form used. Information usually included name, age, ethnicity/nationality, date of birth, place of birth, address of last residence, name and address of person at destination, and name of nearest relative or friend in former country. You might also find the name of the spouse, names of children or traveling companions, occupation and physical description. Sometimes a photograph of the individual or family is included.

Border entry records are digitized and indexed at Ancestry.com and Ancestry.ca. You can find the following collections by keyword-searching the card catalog (located under the Search drop down menu):

- Canada, Border Crossings from US to Canada, 1908–1935

- Detroit, Michigan, U.S., Border Crossings and Passenger and Crew Lists, 1905–1963

- US, Border Crossings from Canada to US, 1895–1960

Tip: You may hear US records of border-crossers from Canada called “St. Albans lists,” because for many years the records were stored at an Immigration and Naturalization Services office in St. Albans, Vt.

3. Civil Registrations

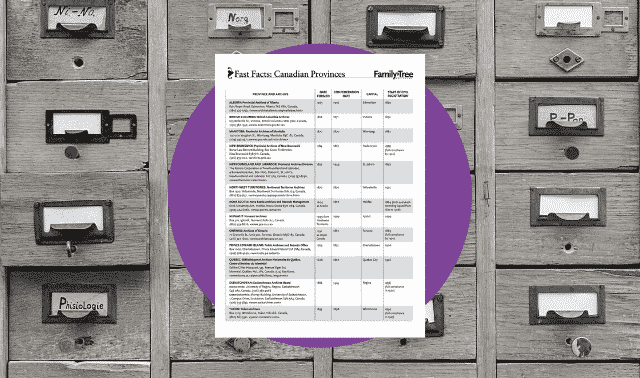

As great as the LAC website is for researching Canadian genealogy, the one type of record you won’t find there is a vital record. Records of births, marriages and deaths in Canada are called civil registrations, and are held at the provincial or territorial level (similar to states holding vital records in the United States).

You can find microfilmed copies of civil registration records that have been released into the public domain at provincial archives (find links to their websites here). If you don’t live close to the provincial archive in the area where you’re researching, you might think accessing these records can be difficult. But many civil registrations can be found online, at FamilySearch, Ancestry.com, Ancestry.ca or the provincial archive’s website.

FamilySearch is a good place to start: From the Search drop-down menu, click on Research Wiki. Next, type Canada into the search box or click North America > Canada on the map. On the Canada Genealogy wiki page, look on the right side menu under Record Types and click on the link for Vital Records. This takes you to the Canada Vital Records wiki page where just about everything you’ll need to know about getting started with birth, marriage and death records in Canada is explained. Here, you’ll find links to each of the provincial and territorial civil registration-vital records wiki pages. (See a tutorial of the FamilySearch Wiki here.)

Accessing civil registrations varies with the province and territory. For example, the Nova Scotia Civil Registration Vital Records page has historical background about the province and its vital registration practices, and links to online Nova Scotia vital records databases both on FamilySearch and the Nova Scotia Historical Vital Statistics. You’ll also find links to the FamilySearch online catalog listings for microfilmed copies of the original civil registration records. If the microfilm has been digitized you will be able to view it at home or your local FamilySearch Center or Affiliate Library.

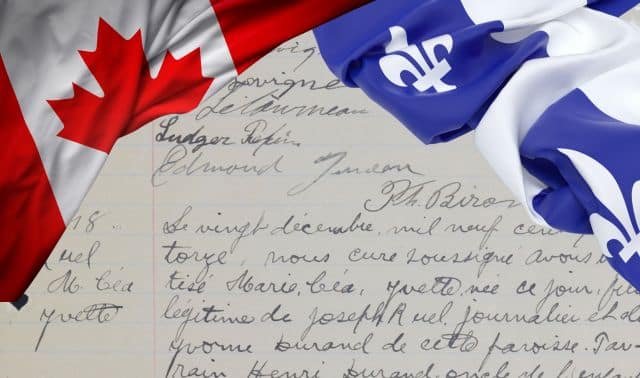

4. Généalogie Québec

Généalogie Québec, which identifies itself as “The Genealogical Site of French America,” is a must for researching French-Canadian ancestry. The online home of the Drouin Institute, it’s available in both English and French—but keep in mind that most, if not all, of the records here are in French. You can research the millions of images and files with an annual, monthly or 24-hour-access subscription.

Collections include the LAFRANCE database of Quebec baptisms, marriages, deaths, plus and Protestant marriages. (Most in Quebec were Catholic.) You’ll also find the Drouin Collection of parish records for New Brunswick, Ontario, Québec, Acadia and the USA; and Quebec census, cemetery and notary records.

A unique feature of this website is that you can search by individual or by couple. Search results for an individual may include baptisms, marriages and burials. Search results for couples may include the marriage and burials of both the husband and wife, plus the baptisms, marriages and burials of all their children.

5. Bibliothéque et Archives Nationales du Québec (BAnQ)

This provincial archives and library of Québec has 12 research facilities in the province that preserve heritage materials from or related to Québec. It also has free online offerings, including:

- a catalog listing BAnQ’s holdings of genealogical dictionaries, maps, family and local monographs, and more

- le Dictionnaire Tanguay (Cyprien Tanguay’s Genealogical Dictionary of French Canadian Families)

- Quebec journals and newspapers

- civil and court records including les Archives des notaires du Québec (archives of public notaries, including guardianship and trusteeship records)

- les Registres de l’état civil du Québec (civil registrations, including baptisms, marriages and burials

Other databases include cemetery, coroner, and prison records.

You’ll notice the BAnQ website is in French. Some pages are also available in English, but you’ll need to use a translator (such as Google Chrome’s translate tool) to intrepret.

To find the site’s main genealogy portal, select Apprendre (Learn). Under Guides, you’ll find pages for deaths (décès), marriages (mariages), births (naissances), and adoptions. The guide for Catalogue de BAnQ : recherches généalogiques provides an overview of the site’s genealogy resources.

6. Homestead Records

Did your ancestors travel West during the late 19th century? Many Canadians, Americans and overseas immigrants came to Canada’s Prairie Provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba to homestead. In 1872, the Dominion Lands Act came into effect in Canada, requiring homesteaders in these provinces and the railway belt of British Columbia to provide proof that their land had increased in value in order to receive land grants from the Crown.

Documents called Letters Patent name these grantees and describe their homesteads and the date the land was granted. The scanned and indexed letters are digitized on the LAC website. Click Discover the Collection in the top menu, then Browse By Topic in the drop-down menu. Next, click on Land Records. Finally, on the left, click on “Land Grants to Western Canada, 1870–1930.” Before you click the Database: Search link, read the information about the land grants to help you find and understand your ancestor’s record.

7. Peel’s Prairie Provinces

Add this free collection, available through the Internet Archive to your list of essential resources for tracing your prairie ancestors. Created by the University of Alberta, Peel’s Prairie Provinces documents western Canadian history and the culture of the Canadian prairies through digitized newspapers, photos and more.

Featured collections here include Peel’s Prairie Postcards, containing more than 15,000 images; the Magee Photographs Collection; and Henderson’s Directories listing residents and businesses of various cities and regions as far back as 1905. You can keyword-search the collection of 100-plus digitized historical newspapers dating.

The website also gives you access to the Peel Maps collection and the Peel Bibliography, a collection of digitized books in English, French, Ukrainian and other languages. You can search both of these collections using keywords, subject, author or title.

8. Records of the Great War

Then part of the British Empire, Canada was involved in World War I (often called “the Great War” around the world) from its beginning in 1914. Of the roughly 424,000 who served overseas in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), about 60,000 were killed. Some Britons and Americans served with the CEF, as well. In observation of the WWI centennial, LAC has digitized CEF service records and the originals are no longer available to view.

To access these records, start on the LAC home page and click First World War personnel files under Most Requested > Collection. You can search by name among service files, attestation papers (for volunteers) and Military Service Act enlistment forms (for draftees) of approximately 622,000 men and women.

Each CEF service file may contain up to two or three dozen forms. Details about CEF members may include full name, date and place of birth, name of parents, marital status, name of spouse, last known address, enlistment training, medical and dental history, hospitalization, discipline, discharge or notification of death, and more. The unit(s) to which the individual was posted are listed in the service file, but they don’t specify the actual theatres of war where the CEF member fought.

9. WWII Records

During World War II, more than 1.1 million men and women in Canada and Newfoundland served in the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force. More than 44,000 members of the Canadian forces lost their lives in service between 1939 and 1947.

The files for those who died in service are publicly accessible. Included in this collection are those who were killed in action, who subsequently died of wounds or injuries related to service, and who died as a result of accident or illness while in service.

To find these records on the LAC site, go to Personnel records of the Second World War. (Learn more from the Military History page.)

Documents in the service files include enlistment papers with details about the individual such as full name, date and place of birth, names of parents, spouse and siblings; medical records; dental charts; as well as military units (for army service), ships on which they served (navy) or the squadrons with which served (air force). Evaluation reports, medal entitlements, death registration, burial details and estates records also are in these files.

10. Historical Newspapers

You might find it frustrating to research old Canadian newspapers on the internet. There’s no single online repository. Many newspaper titles don’t include the town or city, making it a challenge to determine if a particular paper was published in your ancestor’s area.

The Ancestor Hunt has made researching historical newspapers a lot easier. Site owner Kenneth R. Marks has organized lists of historical Canadian newspapers by province or territory. You can access these lists from the home page by clicking on Resources > Newspaper Links from the top menu and then scrolling down to the section on Canada. There, you’ll see links to pages for each province and territory.

Each provincial page contains an overview of available titles, followed by links to online collections of specific papers, organized by free/fee-based sites and then by place. Clicking on a newspaper title takes you to that paper on the Google News Archive or a repository website.

11. Early Land Records

Land records are an invaluable resource for researching early settlers in Quebec and Ontario. Land distribution in Quebec was originally based on the seigneurial system, whereby the King of France granted seigneuries (parcels of land) to the upper classes. A seigneur then granted parcels of land to his tenants, who were called habitants.

In 1763, when Britain won the French and Indian War, this system changed for new lands in Quebec (which then covered much of eastern Canada). Quebec was divided into counties, which were subdivided into townships. New land grants were based on the township system. Those wanting land had to petition the provincial Executive Council.

In 1791, England divided the colony of Quebec into Upper Canada (what’s now southern Ontario) and Lower Canada (what’s now Quebec). Both civilian and military settlers submitted petitions for Crown land grants in Upper Canada. Initially, four district land boards oversaw land matters, but these were abolished in 1794, when the Executive Council of Upper Canada took over the land granting process. These land petitions are a great resource for early Ontario settlers, including Loyalists who sided with Britain during the American Revolution and fled to Canada after it ended.

Library and Archives Canada has digitized these records in three collections, all searchable by the petitioner’s name:

- Land Petitions of Lower Canada, (1764–1841)

- Land Petitions of Upper Canada, (1763–1865)

- Land Boards of Upper Canada, (1765–1804)

To access them, click on the now-familiar Discover the Collection tab on the LAC homepage, then choose Browse by Topic, then Land Records. Read the information about each of the collections to learn about the records, what you can expect to find and how best to search them.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, October 2024.