But the Great White North is more than maples, moose and Mounties. The vastness of the world’s second-largest country is matched by its rich genealogical resources. Such a records abundance can be as intimidating as a wide-open prairie — where to begin? US researchers may be surprised to encounter different record-keeping systems so close to home. And though Canada’s census years match its former mother country, Britain, you can’t assume other genealogical similarities.

To help you get started, we’ve asked three genealogical experts — Dave Obee, co-author of Finding Your Canadian Ancestors: A Beginner’s Guide (Ancestry); Pat Ryan, a professional genealogist in Canada; and Louise St. Denis, director of the National Institute for Genealogical Studies <www.genealogicalstudies.com> — to clarify the best strategies for finding Canadian kin. So if you’ve been putting off exploring your Canadian ancestry because you don’t know where to start, or your search is frustrated by brick walls, use our guide to get on the right track.

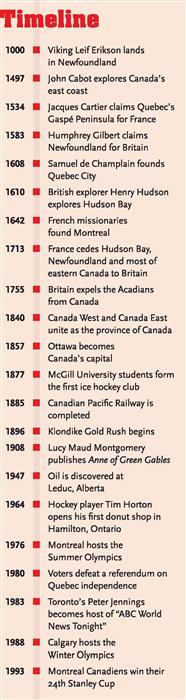

Illuminating history

“Remember, Canada is a relatively young country, with most of the settlement coming in the past century and a half,” Obee says. “More than likely, it won’t be the final destination in research, but rather a stop on the way to another country.” He stresses the importance of using resources in those places, including the United States.

Not recognizing the frequent migration between the US and Canada may be your biggest genealogical mistake, Ryan notes. “Sometimes people went back and forth over the decades, while others simply passed through Canada on their way to the united States. There were quite possibly Canadian records created about them,” she says.

“I think the biggest challenge people have is just understanding the size of this country and how different the regions are within the country,” says Ryan. “In this massive country, our entire population is approximately the same as that of California. It’s like searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack.”

So before you begin, you’ll want some knowledge of Canada’s diverse geography and history. Obee notes most European-ancestored people with Canadian roots going back more than 150 years should focus on provinces from Ontario and eastward: These were settled first, beginning in the late 15th century, by Britain and France. The French went for the St. Lawrence River Valley and Acadia (now the Maritime Provinces). French fur traders and Catholic missionaries explored the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay. England settled Newfoundland in addition to its 13 southern Colonies.

In 1763, after the Seven Years War — during which England expelled 75 percent of Acadia’s French population — France ceded nearly all of its North American colonies to Britain, Quebec in particular retained its French identity and language, and today’s Canada is officially bilingual.

An influx of 50,000 British loyalists after the American Revolution led to reorganization of the Maritimes, including New Brunswick’s split from Nova Scotia. A 1791 act separated French-speaking Lower Canada (generally, today’s Quebec) from English-speaking Upper Canada (now mostly Ontario), each with its own government. Confederation came in 1867, when the union of Britain’s North American colonies, provinces and territories made Canada a federal dominion. The Canada Act of 1982 capped off a gradual process of independence. Today, Canada is a self-governing parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as head of state.

With 10 provinces and three territories, Canada’s borders have shifted as new administrative divisions formed and place names changed-important to know, since most records were created and stored locally. You’ll have a hard time finding records if you don’t know where your Canadian family lived. “Canada today is a different country than it was even just 100 years ago. For instance, provinces themselves are different in size, shape and name from years gone by,” says Ryan. She suggests searching historical maps and gazetteers to locate your family.

Take a crash course on Canada history through books in our online toolkit <www.familytreemagazine.com/canadian> and on sites such as Early Canadiana Online <www.canadiana.org/eco.php>. You’ll find map resources at your library, through the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> and at Genealogy Unlimited <www.genealogyunlimited.com>. Get location details on towns, villages, mountains and other places by searching the free Geographical Names of Canada database <geonames.nrcan.gc.ca/index-e.php>.

Clarifying boundaries

Just beginning to search for Canadian ancestors? Obee says it’ll help to know whether your ancestor’s federal, provincial or local government created the records you need. “Odds are researchers will be dealing with records created by provincial governments most of the time,” he says.

Canada’s national archives, called Library and Archives Canada (LAC) <www.collectionscanada.ca/index-e.html>, is located in Ottawa with four smaller offices around the country. It holds federal records such as censuses and passenger lists; you can order photocopies by following the instructions at <www.collectionscanada.ca/genealogy/022-901-e.html>.

You’ll find yourself visiting LAC’S online Canadian Genealogy Centre <www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/genealogy/index-e.html> again and again for its digitized records and finding aids. Don’t miss the free Tracing Your Ancestors in Canada PDF, which you can download by clicking the Guides link under Learning Resources.

Each province also has its own archives, separate from LAC. Generally, you’ll find vital records, tax records and certain land records among their collections. Many provincial archives also have regional locations — Quebec, for example, has nine — so you’ll need to call or surf the archives’ Web site to figure out which location has the materials you’re looking for.

Link to Canada’s provincial archives from <www.archivescanada.ca/car/car_e.asp?|=e&a=b&f=provincial>. LAC and six provincial archives collaborate on a Web tool called That’sMyFamily <www.thatsmyfamily.info>, which lets you search those repositories’ online databases in one place.

The FHL has a large collection of Canadian microfilm, too, which you can access through its branch Family History Centers (see <www.familytreemagazine.com/fhcs> to find one near you). Run a place search of the online catalog on your ancestor’s province, county, township, town, city or parish to find census, church and immigration records, plus directories, maps, how-to guides and more. Access the FHL’s Canadian research outlines from FamilySearch by clicking the Search tab, then Research Helps, then scrolling down the alphabetical list to the outline you need. Online courses such as those from GenClass <www.genclass.com> and St. Denis’ National Institute will help, too.

Obee’s CanGenealogy.com <www.cangenealogy.com> organizes links to Web sites in order of importance (rather than alphabetically) for provinces and key topics — great if you’re at a loss for where to begin. Our experts also recommend The Canadian Genealogical Sourcebook by Ryan Taylor (Canadian Library Association), and Eric Jonasson’s The Canadian Genealogical Handbook, 2nd edition (Wheatfield Press). See our online toolkit for more resources.

Recognizing records

Start your Canadian ancestral research in census, immigration, land and vital records — all explained here. Once you’ve gotten your feet wet, you’ll move on to resources such as military records, wills, probates and cemeteries.

• Census: Canada’s first census was in 1666, when it was New France, and various colonial and regional censuses followed. National censuses began in 1871 and happened every 10 years; Northwest provinces were enumerated in 1906. The most recent census available today is 1911. Census returns before 1851, though, are rarely complete for any geographical area and usually list only the head of household.

In 1891 and earlier; censuses asked for age, sex, religion, occupation, country of birth and race. The 1901 census added questions about the exact date of birth, citizenship and immigration year.

The FHL has all available Canadian censuses on microfilm — run a keyword search of the online catalog on canada census to find them. Records are arranged by province or territory, then divided into districts. Districts could change between censuses and were based on Canadian electoral districts, which usually corresponded with counties and cities. Census districts were divided into subdistricts, generally corresponding with townships, parishes and larger towns.

If you’re using microfilm records, you’ll need your ancestor’s district and subdistrict. Find districts for each census and link to databases of 1901, 1906 and 1911 census records at <www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/genealogy/022-911-e.html>. Since the censuses aren’t indexed by name, you’ll need to search by district, town, county or other geographic location. Then browse images of the matching records.

But first, try Automated Genealogy <www.automatedgenealogy.com>, which hosts ongoing projects to index the 1901, 1906 and 1911 censuses. If you subscribe to Ancestry.com ($155.40 per year) or Ancestry.ca ($83.40 Canadian per year), you can access name indexes for the 1851 (incomplete), 1901, 1906 and 1911 censuses. Your local library may offer a version of the databases free through Ancestry Library Edition. For those with Quebecois ancestors, St. Denis says, “be sure to search for maiden names. In the French speaking areas of Quebec, census takers record the woman’s maiden name.”

• Migration: As a British colony, Canada was the natural recipient of hundreds of thousands from the United Kingdom — Scottish, Irish, English, Welsh and some Australians. Canadian passenger lists dating from 1865 to 1922 are online <www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/archivianet/passenger/001045-130-e.html>, but they’re not indexed by name. Instead, search by ship name, departure port and date, or arrival port and date. Don’t know this information? You’ll have to estimate a date and place, then browse the lists. Immigrants quarantined at Grosse-Ile — the entry point for 4.3 million people, downstream from Quebec City — are listed at <www.collectionscanada.ca/archivianet/grosse-ile-immigration/index-e.html>.

Between 1919 and 1924, Canada required an individual manifest (called Form 30A) for each immigrant. Though not all ports complied, Form 30A has details such as religion and citizenship. These forms and the 1925-to-1935 passenger lists show each immigrant’s name and birthplace, the name and address of the person he was meeting, and name and address of the nearest relative in his homeland.

Passenger records are arranged by port and date of arrival. You can see a list of available ports and years in LAC’s online immigration records guide <www.collectionscanada.ca/genealogy/022-908-e.html>. Film is available both through the FHL and LAC. Ancestry.com and Ancestry.ca have some databases of immigration-related record transcriptions; search by name and use the citation to find the original record.

Canada created no comprehensive immigration lists before 1865. LAC has microfilm of a few surviving records, plus an online database of the 1832 Montreal Emigrant Society Passage Book. You can search 15,000 names of British immigrants between 1801 and 1849 free through InGeneas <www.ingeneas.com>.

Many immigrants to Canada, especially from Europe, landed at US ports and traveled north overland. Prior to April 1908, they were allowed to move freely across the border into Canada; since no entry records exist for that period, trace those immigrants in US port passenger lists (see the August 2004 Family Tree Magazine for help). The LAC holds lists of border crossers from April 1908 through 1935; FHL microfilm spans 1908 to 1918. The records don’t cover everyone, including those who crossed the border when registration stations were closed, had lived in Canada or had a Canadian parent.

In the 1890s, the US government caught on to the large number of people who, hoping to avoid the lengthy US immigration process, sailed to Canada and traveled south to the United States. They had to check in starting in 1895. Those border entry records are called the St. Albans Lists, for the Vermont town where they were kept. They generally don’t record people of Canadian birth until 1907. You find the records at Ancestry.com, as well as on microfilm at the FHL and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> in Washington, DC.

• Land: Land was surveyed differently in eastern Canada than in the west, resulting in different records. In the east, early settlers submitted petitions to the governor for Crown land. In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, these records are in the provincial archives. LAC has them for Lower Canada and Quebec (1764 to 1841), and Upper Canada and the United Province of Canada (1791 to 1867), a brief merger of Quebec and Ontario from 1841 to 1867. A separate commission heard claims for the Gaspé District in Quebec.

You can follow links to LAC’s online indexes for Lower Canada and Gaspé District records through its helpful Provincial Land Records <www.collectionscanada.ca/genealogy/022-912-e.html>. In most cases, the indexes provide the year, volume and page number of the original record, plus a microfilm number. Use the information to request microfilm copies from the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec (Quebec national archives).

In Quebec, under the seigneurial system, the king would grant land to prominent families or members of the military, who could then make his own grants, a practice that continued until 1854. Notarial records, available at the Quebec archives, captured these transactions. Find instructions for searching them at <www.collectionscanada.ca/genealogy/022-914.001-e.html>.

Many people from Ontario moved west to Manitoba in the 1870s, when the government opened land for homesteading through dominion land grants. A few decades later, free land attracted hundreds of thousands of Europeans to Western Canada. When homestead land became scarce in the United States, land seekers there moved north to Saskatchewan and Alberta, where terra firma was plentiful. “Alberta has stronger ties to the United States than any other province,” Obee says.

The LAC holds letters patent for Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta through 1930; search a Western Land Grants database of them at <www.collectionscanada.ca/archivianet/western-land-grants/index-e.html>. Letters after 1930 are at the provincial archives, as are all the resulting — and more-detailed — homestead files. You may discover some surprises, such as vital records, wills, divorce papers and even personal correspondence.

Records of local land transactions are also in provincial archives and at local record offices. You’ll learn more about where to look in LAC’s land records guide.

• Vital: In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Canadian provinces and territories began keeping civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths. Before then, these events were recorded in church registers.

As with US vital records, you’ll need to make sure you address your civil registration inquiry to the right office, and you may come across privacy restrictions. Get contact information for provincial vital-records offices at <www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/genealogy/022-906.006-e.html>, plus details on availability, as well as civil and church registrations the FHL has microfilmed.

For French Canadian ancestors, investigate the Drouin Collection volumes of baptisms, marriages and burials from 17th- to 20th-century church records. Access the records through Ancestry.com, at large genealogy libraries and at <www.genealogie.umontreal.ca/en> (you can search free, but have to pay for full details). You’ll come across dit names, which St. Denis describes as aliases people used in place of or with their surnames (dit is French for “also known as”). “Don’t ignore them,” St. Denis says. “If you run into a brick wall, check the dit names.” Learn more about researching with dit names at <www.francogene.com/quebec/ditnames.php> and see the French Canadian research guide in the June 2006 Family Tree Magazine.

For ancestors in Nova Scotia, check the provincial vital-statistics database <www.novascotiagenealogy.com> of more than a million birth, marriage, and death records. View records online, then download them for $9.95 or order paper copies for $19.95. The site also has other databases, including poll taxes, marriage bonds and Halifax death registers.

Ancestry.com and Ancestry.ca have records of Ontario births (1869 to 1909), marriages (1857 to 1924) and deaths (1869 to 1934) — databases Obee finds useful because you can search by the mother’s maiden name, helping to overcome the lack of a Soundex system for Canadian censuses. “By looking for births where the mother’s maiden name was McKennitt, I tracked down several lines. One McKennitt woman married a man named Minke, then disappeared. Birth records revealed his name was Moehnke, not Minke.”