If you want a quick gauge of how Canada has influenced the culture “south of the border” in the United States, just turn on your television. After the nightly news hosted by Canadian Peter Jennings, you can match wits with Canadian Alex Trebek on “Jeopardy!” and beam up a “Star Trek” rerun starring Canadian William Shatner. Flipping the dial, you’ll probably spot fellow Canadians Mike Myers and Michael J. Fox. But it’s not just TV: Think Celine Dion, Margaret Atwood, Wayne Gretzky, the Cirque du Soleil, Titanic director James Cameron …

If you want a quick gauge of how Canada has influenced the culture “south of the border” in the United States, just turn on your television. After the nightly news hosted by Canadian Peter Jennings, you can match wits with Canadian Alex Trebek on “Jeopardy!” and beam up a “Star Trek” rerun starring Canadian William Shatner. Flipping the dial, you’ll probably spot fellow Canadians Mike Myers and Michael J. Fox. But it’s not just TV: Think Celine Dion, Margaret Atwood, Wayne Gretzky, the Cirque du Soleil, Titanic director James Cameron …

The ancestries of Canadians and people in the United States are as intermingled as our cultures. Between 1851 and 1951, for example, more than 6.5 million Canadians immigrated to the United States. Most of them never became as famous as Peter Jennings or got to command the Starship Enterprise — but they may have become your ancestors.

In my own family, the links to Canada are only a couple of generations away. My maternal grandparents emigrated from Quebec to New England at the beginning of the 20th century, leaving behind a portion of their extended family. They traveled back to Quebec several times to visit cousins. I remember visits being surrounded by another language — French — that my mother used when she didn’t want the children to understand her conversations with her siblings, and food nothing like we had at home — head cheese and blood pudding. These visits helped me discover new family and a whole history I was unaware of; digging into your own Canadian roots can do the same for you.

The name Canada comes from the Huron-Iroquois word kanata meaning “village.” But this is a vast “village,” formed of 10 provinces and three territories (including the new territory of Nunavut created in 1999). The good news for genealogists is that while Canada is physically larger than the United States, most of the population lives within a few hundred miles of the US border. This makes searching for ancestors more manageable.

But you should start even closer to home, interviewing relatives and exploring family documents. Tracking down those clues is especially important in Canadian research. Since many Canadians came to the United States within the last century, it’s possible to find immigration tales within a couple of generations. It was also quite common for people to immigrate to an area where other family already resided. If you’re aware of other Canadian relations and know where in Canada they lived, start there. The closer the kinship, the more likely your ancestor came from the same place or somewhere close by.

After exhausting these home sources, create a list of books, documents and microfilms to consult, noting where they’re located. The holdings of the National Archives of Canada, the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City, the National Library of Canada and the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) are good places to begin. Canada’s National Archives makes many of its resources available through interlibrary loan, and you can borrow microfilm from the FHL through your local Family History Center. NEHGS offers some materials on loan to members. And all these libraries have online catalogs to help you find resources.

If you’re interested only in one province’s records, find a regional genealogical society on the National Archives of Canada Web site <www.archives.ca/08/08_e.html>. Don’t forget to try genealogical societies in your area with a Canadian interest, such the American-French Genealogical Society in Rhode Island. Also consult the list of Canadian Archival Resources on the Internet <www.usask.ca/archives/menu.htm>. Angus Baxter, author of the excellent In Search of Your Canadian Roots (Genealogical Publishing Co.), adds that Canada’s public libraries are good sources of local family history information.

As you begin your research, aim to answer these three questions:

• Why did your ancestors immigrate to or from Canada?

• Where did they first settle?

• Whom did your ancestors immigrate with?

WHY CANADA?

People had many reasons for immigrating to what is now Canada. The first permanent white settlers were military men and a few hardy colonists. Disagreements between the French and British governments over Canada began when these countries created small colonies in similar territory at the same time. Armed forces protected settlers from skirmishes with native peoples but also maintained the land claims of England and France. Many of these professional soldiers stayed in Canada, establishing families and purchasing land.

In 1763, after more than a century of military encounters, England’s superior sea power and the pressure of its other American colonies forced France to finally relinquish most of its claims to Canada. In 1774, England passed the Quebec Act that protected the formerly French area’s Catholic religion and civil law even while ruled by Protestants.

Canada’s French heritage can present a hurdle for research in some provinces, particularly Quebec. According to the NEHGS’ Michael Leclerc, author of numerous articles on French Canadian research, record-keeping in Quebec follows French customs rather than English law. Notaries kept track of a variety of transactions, including marriage intentions. The British government let Quebec’s citizens retain this coutume de Paris (Parisian custom) to placate them after France relinquished its claims in 1763. This means that all records in Quebec are in French regardless of the language spoken by the resident. You’ll want to bone up on French words and phrases as well as record-keeping practices. See “The French Connection” in the June 2001 Family Tree Magazine for tips on using French records.

Quebec isn’t the only province with a French past, though. Nova Scotia (including present-day New Brunswick) was the first Canadian colony settled by immigrants from France in 1604, when it was known as Acadia. The Acadians were expelled from 1755 to 1762 when they refused to fight against Nova Scotia; many fled to Louisiana where they began the Cajun culture there. Acadian descendants can find material on their ancestors through the Confederation of Associations of Families Acadian. Its Web site <www.cafa.org> contains an index of Acadian/Cajun families.

English-speaking exiles, too, immigrated to Canada. During the American Revolution, thousands of Loyalists left the American colonies to settle in Nova Scotia, eastern Quebec and Ontario. After the Revolution, “United Empire Loyalists” moved into part of Nova Scotia that would become New Brunswick. The National Archives of Canada has microfilms of Loyalist papers and British military records that can help you trace these ancestors.

The American Civil War sparked Canadian unity, resulting in a confederation established by the British North America Act of 1867. But provinces were slow to join a united Canada, the last holdouts being Newfoundland and Labrador in 1949.

Besides soldiers and settlers, Canada’s vast wilderness also attracted men who sought adventure. In fact, the original name of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 was a “Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.” Their mission was to explore and settle the areas now known as Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and part of British Columbia. Today the company is known for its chain of retail stores rather than fur trading, but it ran frontier trading posts for 200 years until selling its land to the Canadian government in 1869. The company archives <www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/hbca>, now owned by the Provincial Archives of Manitoba, are a wonderful resource for genealogists.

And don’t forget Canada’s native population, which numbered 300,000 at the time of European settlement. Oral histories in many Canadian families suggest marriages between settlers and the native peoples. To find documentation for such stories, you need to seek out materials such as field office records for the office of Indian affairs plus affidavits for the Department of the Interior stating parentage and ethnic origin of spouse. Recently, tribes in Canada such as the Inuit banded together as a group called The First Nations, to further joint political purposes while retaining their separate languages and culture. Genealogical documentation is required to prove membership in a First Nations tribe.

ACROSS THE BORDER AND OVER THE SEAS

While most original colonists came from either France or England, not all Canadians originated from just those two countries. The 19th century saw an influx from Scotland and Ireland to Nova Scotia, for example. After World War II, Central and Southern Europeans immigrated to other areas of Canada.

The trans-Canadian railway linked the country in 1885, spurring movement to western provinces that beckoned immigrants with farm land. The railway also brought a diversity of people, from German Mennonites to a few hundred Welsh immigrants who’d spent time in Argentina. Immigration to Alberta included Mormons from Utah, Germans, Scandinavian immigrants from northern US states and Canadians from Ontario looking for better farming conditions.

The migration went the other direction, too. My grandparents were part of one of the largest migrations from Canada, between 1871 and 1901, when more than a million Canadians immigrated to the United States seeking economic prosperity.

The family of Grant Emison, a researcher who grew up in Texas, originally immigrated to the United States, ended up in Alberta and then moved back to the United States, all within a few generations. Don’t be surprised to find similar patterns within your own family. Land records, including homesteader claims at the provincial archives, can help track these mobile ancestors.

Unfortunately, just knowing where your ancestors settled doesn’t verify where they originally came from. Finding passenger manifests to answer that mystery can be difficult. While Canadian officials began keeping records in 1865, not all periods are covered or complete. Many of the passenger lists to New Brunswick, for example, were destroyed in a fire at the Customs House in 1877.

But there are several resources you can tap. In Nova Scotia, a new museum, Pier 21 <www.pier21.ns.ca>, has a database and microfilm archive of anyone who entered a Canadian port between 1925 and 1935. If your relatives traveled between Canada and the US during the period 1895 to 1954, look for them on the passenger and immigration lists known as the St. Albans List, named after the border-entry point at St. Albans, Vt. These lists actually document individuals who crossed the entire Canadian border, not just at Vermont. Marian Smith of the US Immigration and Naturalization Service has an online article that explains how to use these records and why they’re so valuable at <www. nara.gov/publications/prologue/stalbans.html>.

TRAVELING IN GROUPS

In A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Immigrant & Ethnic Ancestors (Betterway Books), Sharon DeBartolo Carmack describes how immigrants often traveled in groups to a new country, settling together in a particular town or neighborhood. One example of this is tiny Prince Edward Island (PEI). Because PEI remained relatively unconnected to the mainland until the Confederation Bridge replaced ferry services, this was and still is a close-knit community. Many of the families on the island descend from Scottish colonists who settled PEI and intermarried. This means that if you discover an ancestral link to the island you’re apt to find all kinds of connections.

When your relatives immigrated from Canada to the United States, they often followed the trail of other family members. My Bessette relatives weren’t the first family members to seek out new opportunities in the United States. They let other members of the family establish themselves first, providing a foothold in the new area. Following the ancestral trail backwards leads to a whole series of new places to look for records.

So if you think you’ve hit a brick wall in your Canadian roots, try going sideways. Can you find where cousins or even neighbors of your ancestors came from in Canada? Chances are, that’s where your immediate kin immigrated from as well.

YOU WANT RECORDS, EH?

Once you have a general sense of where your Canadian relatives lived, learn more about the province at the time they arrived in order to find documents. Fortunately for genealogists, each province and territory maintains an archive rich with genealogical treasure and open to the public for research. Web sites for each provincial archive outline their holdings of genealogical research and their policies (see next page). For instance, the site for the British Columbia Archives <www.bcarchives.gov.bc.ca> features searchable vital-record indexes to British Columbia birth registrations for 1872 to 1899, marriage registrations for 1872 to 1924 and death registrations for 1872 to 1979, as well as more than 65,000 image files and a virtual museum. While the staff is helpful at all the facilities, you’ll find the research atmosphere in New Brunswick particularly welcoming. The New Brunswick provincial archives has a special genealogical section and has published a leaflet to help researchers, Genealogical Resources at the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. Bear in mind that some of the western facilities are little more than 100 years old. For instance, Yukon only became a separate territory in 1898. When looking for materials that predate formation of the province or territory, consult the archives for the region before separation.

While many of the Canadian resources available to researchers will be familiar, such as city directories, land records, vital records and census documents, you will notice some differences. Let’s look at some specific resources for genealogical research in Canada:

Censuses: Just like the United States, Canada now takes a census every 10 years. The first census dates from 1666, but there’s a long gap in nationwide enumeration until the first Dominion census in 1871. Census documents exist on the provincial level for the 17th through 19th centuries, though the returns are scattered. Information on the census forms varied, but after 1851 they listed all household inhabitants. The censuses up to and including the 1901 enumeration are open to the public for research. (Unfortunately, you may never get access to later returns. Statistics Canada, which compiles the census, won’t release post-1901 records to the National Archives — even after the regular 92-year privacy period expires. The agency believes that the Statistics Act of 1906 prohibits their release. See <www.globalgenealogy.com/Census> for more.) You’ll need to use city directories and similar resources to narrow your search; since the censuses aren’t generally indexed, knowing your ancestor’s street address can be a huge time-saver.

To access the Canadian census, you can tap microfilms available through the FHL as well as the National Archives of Canada and the NEHGS. For a preview of what the FHL has, go to <www.familysearch.org/Eng/Library/FHLC/frameset_fhlc.asp>, click Place Search and type in a province. Scroll down the results and you’ll see all the censuses for that province accessible through the library.

Some actual census data is also online, but not entire census reports. The best place to look is at Censuslinks <censuslinks.com> (choose Canada from the home page), a site that connects researchers to online census material. If you’re transcribing census records for a particular area, consider participating in the award-winning Canadian Genealogical Projects Registry <www.afhs.ab.ca/registry>, a project of the Alberta Family Histories Society.

Civil registration: Registering births, marriages and deaths was a complicated affair in Canada. In most provinces and territories, legislation for formal civil registration wasn’t put in place until late in the 19th century. This doesn’t mean that vital records weren’t kept, just not on the governmental level. In Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, church records date from 1752 although civil registration didn’t start until 1892.

Religious records: Given Canada’s late start on official vital-record-keeping, you’ll have to rely heavily on religious records of births, deaths, marriages and so on. First you’ll need to determine your ancestors’ religious affiliations. Among the many religious groups who settled in Canada are Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Mennonites and Quakers. Catholic records are particularly good, with women’s maiden names recorded as part of the marriage record. Many of these parish records are in print courtesy of the American-French Genealogical Society <www.afgs.org>. The Toronto diocesan records are on microfilm at the Family History Library.

Your search for religious records can be complicated. According to author Baxter, church registers may be in various places, including denominational or provincial archives, individual churches and the National Archives.

Military records: The soldiers who accompanied colonists served for the French and British governments, so finding military service records can mean recrossing the ocean if you don’t find answers in provincial archives. Good places to start are the Public Record Office <www.pro.gov.uk> in England, which has a helpful publication called Tracing Your Ancestors in the Public Record Office (PRO), and the Bibliotheque Généalogique et d’Histoire Social <www.geocities.com/Eureka/1568> in France.

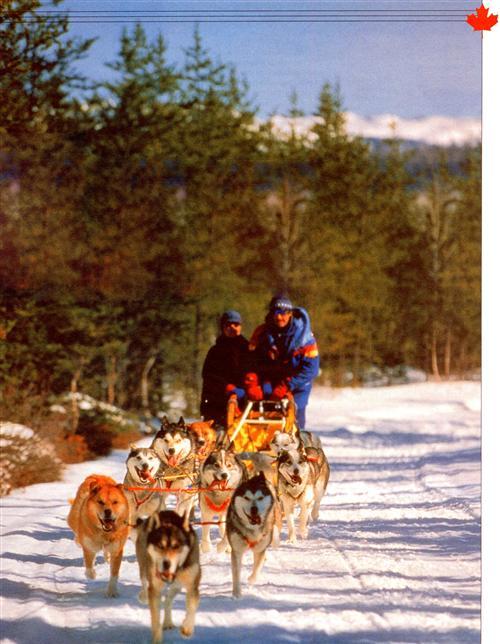

Eventually, if you live in the United States, you’ll want to seek your Canadian cousins in person, just across the border. While you’re busy researching your roots, try to plan your visit to coincide with one of the many festivals that enliven Canada all year long, from the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario to the international flavor of Folkorama in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Even the long winters don’t deter Canadians from enjoying themselves — see for yourself in Quebec City at the Winter Carnival in February when enormous ice sculptures dominate the city and the party takes to the streets.

Or you could always just turn on “Jeopardy!” and show off your smarts to fellow Canadian Alex Trebek: “I’ll take Canadian ancestors for $1,000, Alex…”

From the April 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine