If you’ve traced your family back to 1850 in the United States, congratulations! As you peer deeper into the past, you may find the trail is harder to follow: Where are all the names? Gone are federal census records that list everyone by name and age, replaced by enumerations naming only heads-of-household. Outside of New England, birth and death records become virtually non-existent. Grave markers may be lost or unreadable. Documents have been lost to disasters and the ravages of time.

On top of all this, your ancestor could’ve moved around in search of land or opportunity, leaving behind only faint, scattered clues. Compared to relatively prolific paper trails of later years, pre-1850 records can seem few and impersonal: more like a fossil record than an archival one. Yet the truth is that you can find your ancestors even without birth, death and every-name census records. You just need to know what documents likely do exist—and to be willing to dig for them.

The following strategies can help you identify family members before 1850. Each offers favorite databases for early American research and examples of what you may find. With a little practice, you’ll soon be dusting off long-buried details that bring your family’s pre-1850s history back to vivid life.

1. Study the Region

Learning about the geography and history of an ancestor’s region is the first key to finding him. In the early 1800s, county and state boundaries were still changing in much of the United States. That can affect where you’ll find extant records today. Even if your family never physically moved, information about them might be scattered in other jurisdictions that did change.

Map out state and county boundary changes on the free Atlas of Historical County Boundaries and Randy Majors’ Historical US County Boundary Maps. You also can look for boundary change descriptions or maps in old atlases and county or local histories.

Of course, not everyone stayed put. This was a time of widespread migration as the nation expanded. New states and territories were rapidly being settled. One of the biggest challenges family historians face is tracing an ancestor from where he lived in the mid- or late-1800s (say, Missouri) back to where he was born or lived before that (say, Pennsylvania).

To successfully identify that Pennsylvania hometown, you’ll likely first need to learn all you can about him and his family in Missouri. Historical records there may directly identify a family’s previous hometown. More often, they provide clues based on the town’s settlement patterns and dominant ethnic groups, religion, industry and employers.

2. Make the Most of Census Marks

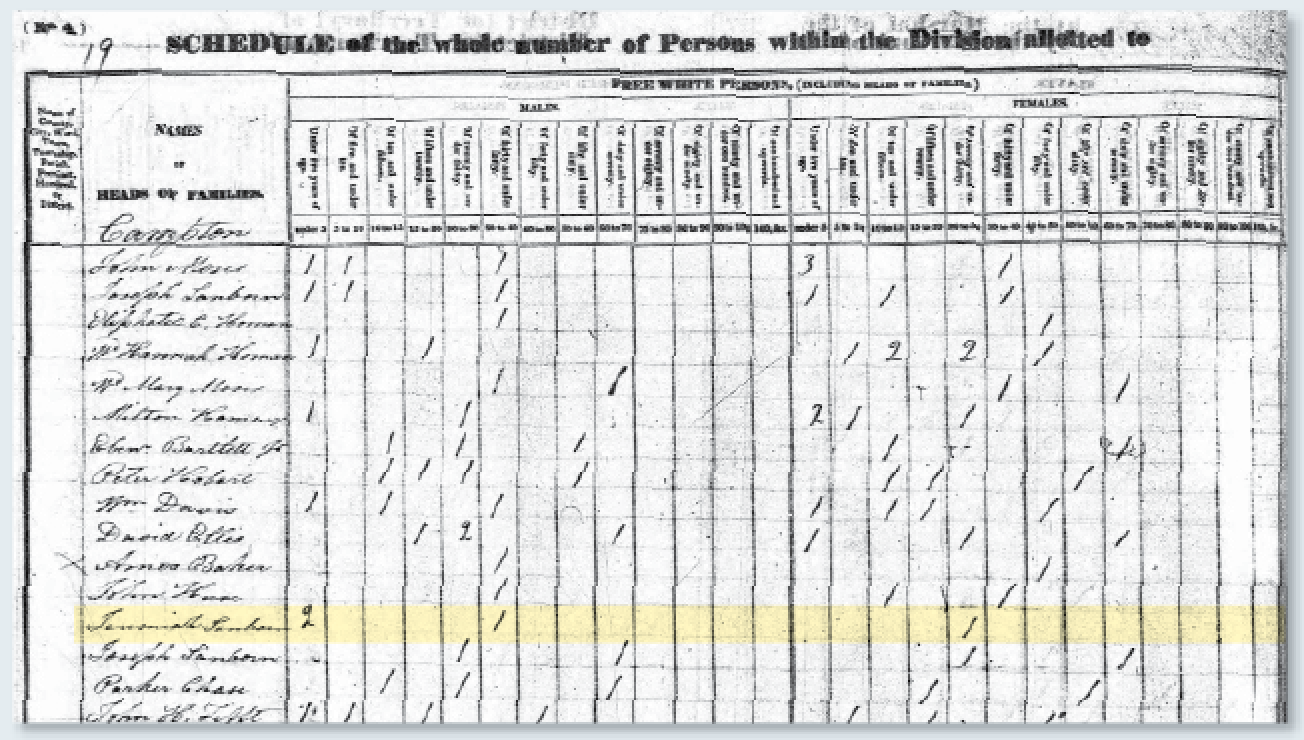

US census records from 1790 to 1840 look vastly different from those of later decades. The only person named is the head of household: the landowner or person supporting the family. Though typically the father, this could be a widow, grandparent or other relative. Members of the household are counted by tick marks or numbers indicating their sex and age range, such as “Free white females of sixteen and under twenty-six.”

If you know where your family lived, search for a potential head of household in census records on Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, Findmypast or MyHeritage. Allow for variations, as spellings often weren’t standardized. Once you find a candidate, the index will indicate how many people were counted in each sex/age group. How do the numbers correspond to known family members? Click through and look at the image of the census to see the names of other householders on the page. They were some of your ancestor’s closest neighbors. Are there others with the same surname? Do you recognize any maiden names of females in your family? If so, you’ll want to look more closely at this family.

If your ancestor moved around, watch for the names of relatives, neighbors and other locals to appear with him in different locations in earlier or later censuses. In the early 1800s, many people migrated in family groups and settled where others from their old hometown settled.

Reading early census records can be tricky because headers on each page weren’t always present or legible.

Try to put names to the tick marks by comparing census records with other details you have about the family. For example, a tick mark for an elderly female in a younger man’s household may be a mother or mother-in-law. (This video shows an example of how to do this in Excel.) Next, compare census results over decades to reveal developments in a family. A household newly listed under a woman’s name suggests recent widowhood. A young couple living near an older family with the same surname may be part of that family’s next generation. Follow up in other records to confirm or refute those theories.

3. Seek Vital Records and Substitutes

Searching for evidence of a birth, death or marriage prior to 1850 can be a long and discouraging process. In many places, these records simply weren’t kept; in others, they’re lost or incomplete. Fortunately, some records do exist. Where they don’t, substitutes might contain the kind of information you need.

First, see what vital resources do exist for that place and time. Search online and consult a reference such as The Family Tree Sourcebook lists available records and contact information down to the county level. The FamilySearch Wiki is another resource. Enter the place name in the search box. A search for Cass County, Missouri, for example, shows it was formed from Jackson County, has no known record losses, and first kept marriage records in 1836. (Check the Wiki for additional record types discussed later in this article, too.)

If your ancestor hailed from Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island or Vermont, you may be in luck. Since colonial times, New Englanders typically recorded marriages and births—sometimes for entire families—in their town journals (deaths were less routinely noted). Modern indexes make it possible to find records even if you don’t know your ancestor’s exact town. Both Ancestry.com and American Ancestors, the website of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, offer town record databases. The FamilySearch Library (FSL) in Salt Lake City has microfilmed many town record books. Search the FamilySearch online catalog by place to see what’s available. The FSL no longer loans film for viewing at local FamilySearch Centers, so look for other copies: In the catalog listing, click the link to view the item in WorldCat and see other libraries that have the film.

Many other states required counties to keep records of marriages long before they began registering births and deaths. Particularly in the Midwest, marriage records often survive back to the time of the county’s formation. Look for searchable collections of county marriage records (many with images of the actual books) on FamilySearch.

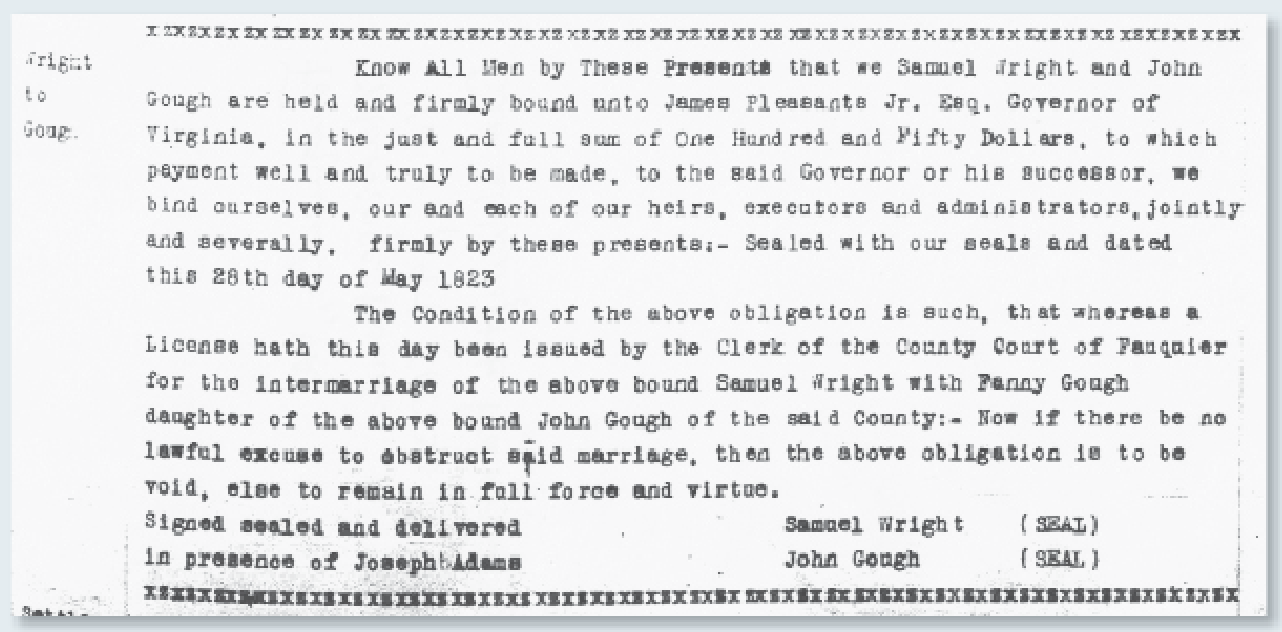

Marriage bonds were issued in some eastern and southern states through the mid-1800s. Bonds offered assurance that an intended marriage would be legal. Although bonds don’t show the date the marriage occurred, they usually provide the names of the groom and the father or guardian of the bride. Bonds are usually grouped with other marriage records in databases. See an example below:

Churches often recorded births, marriages, deaths, burials and family relationships in membership and sacramental records. The availability of church records depends on the place and denomination. While established congregations often kept good registers, frontier settlements typically relied on itinerant preachers.

In places where civil or church records don’t survive, search for other types of records that might provide evidence of births, deaths and marriages. Grave markers are a good place to start, along with associated cemetery records. Look for headstone information at Find A Grave and BillionGraves. Family Bibles, diaries and letters can also be valuable. Check with relatives, local societies and repositories, and on the ArchiveGrid, which links you to libraries’ online finding aids. Then move on to other possible sources of vital information, described below.

4. Follow the Money

Estate records are among the most reliable indicators of kinship for our early ancestors. They’re always worth seeking out. (If your ancestor didn’t own land or sufficient personal property, however, his death may not have triggered an estate settlement.) Someone—usually an heir, but sometimes a creditor—had to initiate the probate process, which could be set in motion with or without a will.

The probate process generated a variety of court records that can shed light on the family, such as:

- Wills: These may name the deceased person’s spouse, children and/or other relatives, along with witnesses.

- Administration letters and bonds: These name the administrator or executor of the estate, the sureties, and sometimes the person’s date of death.

- Inventory and sale: The assessment of the person’s property can suggest his occupation and economic status; those buying his possessions may be relatives.

- Probate packet or file: This might contain due bills, receipts, claims, accounts and other papers full of clues about a person’s life and origins.

- Final account or distribution: This states the final value of the estate, and might list the heirs.

- Guardianship papers: These were created when minor children of the deceased inherited property of sufficient value to require protection until they came of age.

Probate records are often still at the courthouse where they were created. Published county or statewide indexes can help you locate those you need. Some probate records are microfilmed and even digitized on websites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. In fact, Ancestry.com hosts an enormous collection of wills and estate records, with over 170 million documents from all 50 states (not comprehensive for all locales and time periods).

Tax records also can help with your research, though more indirectly. Studying personal property tax records over a period of years can reveal when someone died or moved away, as well as when a young man came of age to pay taxes. Look for microfilmed tax records at the state archives or the FamilySearch online catalog.

5. Track the Land

Your ancestors’ land transactions can yield a surprising amount of information about them. Deeds usually state the place of residence for both the buyer (grantee) and seller (grantor). This can help you track migrations from one place to another. In addition, deeds often name the seller’s wife, because she was entitled to a certain amount of her husband’s property under dower laws. If she was a widow, the deed will usually name her late husband. You may find deeds where property was sold for a dollar or simply “for love and affection”—a sure sign of a gift, typically from parent to child.

Deeds can reveal family details that may not have turned up in probate records. For example, some siblings who inherited property jointly might have created quit-claim deeds, whereby they sold their interest in the property to one sibling who wanted to keep the home. If children or grandchildren sold a family property, the person they inherited it from may be named in the deed. Because deeds didn’t have to be recorded immediately, you may find one that contains valuable clues to inheritance many years after the original landowner died.

In most localities, deeds are recorded at the county or town level and remain at the courthouse. FamilySearch has microfilmed many county deed indexes and deed books; check the online catalog to see if yours is among them.

Don’t forget federal land records. Settlers who bought public land from government offices received a patent. Early land patent files have minimal personal details; others have more. Millions of indexed images are on the General Land Office Records website. Print a copy of the patent, then order the corresponding file from the National Archives using NATF Form 84.

6. Explore Military Service

As you develop a profile of your early American ancestor, consider whether he might’ve served in the military. Many communities formed local militia units for protection, and additional companies were raised during times of war. Generally speaking, men born from 1726 to 1767 were eligible for service in the Revolutionary War. Those born from 1762 to 1799 may have served in the War of 1812. Various types of records created from these conflicts could help with your family history.

Begin your search for military records on Fold3. Select the war you’re interested in, then search by name and filter the results by state. Look for these records:

- Service records identify a soldier’s unit, rank, dates of service and muster locations. They typically contain little personal information, but can put you on track to discover more. Revolutionary War service records have been digitized. For the War of 1812, find your ancestor in the Service Record Index, and then order a copy of his service file from the National Archives using NATF Form 86, available at the above link.

- Pension records can reveal much about a veteran’s life and family connections. Depending on the circumstances, you could find the name of his wife or widow, children and other relatives or long-time friends. If a widow applied for a pension, you’ll frequently learn her husband’s date and place of death, her maiden name, and their date and place of marriage. Sometimes a pension file is the only place that information survives. Fold3 has digital images of all Revolutionary War pension files, and is in the process of finishing the War of 1812 pensions. For tips on finding and using pensions in your research, as well as other valuable military records, you can download our US Military Records Free eBook.

- Bounty land records were created when a veteran or his widow applied for a federal land warrant based on military service. Like pensions, they often contain affidavits full of personal details from the applicant and witnesses. Most bounty land claims for Revolutionary War veterans have been combined with their pension records, as have some for the War of 1812. However, the National Archives has a large collection of unindexed bounty land warrant applications. Archivists are working to create an index, which Fold3 is publishing. Order a copy of a pension and/or bounty land warrant file with NATF Form 85.

Don’t forget to draw on the resources of patriotic lineage societies. Dig into applicants’ files to see how they documented their connections back to qualifying ancestors. The Daughters of the American Revolution hosts databases of proven Revolutionary War patriots and descendants. Download member files of interest for $10 to see their supporting documentation. Ancestry.com hosts a database of older applications to the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR); follow up with the SAR Library. The US Daughters of 1812 has an Ancestor Database and record copying service. State chapters of some of these organizations may offer additional resources.

7. Read Between the Lines

Published county and town histories may offer clues to fuel your research, particularly if your ancestor’s children and grandchildren remained in the area. These books were popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and often contain accounts of early settlers. Many out-of-copyright books are now available online at sites like Google Books and Internet Archive. Search for history of and the county or town. Take the information you find with a grain of salt, as few histories disclosed their sources.

Newspapers were a staple of most sizable cities from colonial times, but finding surviving copies can be problematic. Check the US Newspaper Directory, 1690-Present, at Chronicling America for libraries that hold papers from your area. Also try searching the free Chronicling America digitized newspapers database, and subscription databases at GenealogyBank and Newspapers.com. One caveat: Don’t expect to find a detailed obituary for your pre-1850s ancestor, unless he or she was a prominent citizen or lived into the late 1800s. Instead, look for community social news or a brief marriage, court, death or estate sale notice.

Local and state historical and genealogical societies have long published articles on records, events and families in their areas. Many of those publications are more accessible than ever before, thanks to the Periodical Source Index (PERSI) available for searching on the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center website. Since this isn’t an every-name index, try searching by place rather than by surname. If a digitized version of the article isn’t available on the site, request a copy at the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center website (under Genealogy Services, click Research Forms, then Article Fulfillment).

To identify any local histories you may have missed, search WorldCat. Under Advanced Search, enter history and the name of the town and state. Browse individual search results or click on pertinent subject headings in the left-hand sidebar.

8. Pull it All Together

Sometimes, even after considerable effort, you still can’t find a record that directly answers your questions. When that happens, it’s time to see if the indirect evidence points to a particular theory. Creating a timeline of events in chronological order can help you determine whether all your information is consistent, and see potential gaps. More than anything else, though, summarizing everything you know about your ancestor—and how you know it—in writing helps you gather your thoughts and see connections you might otherwise miss. Ask yourself:

- What conclusion does the evidence I’ve found suggest?

- Did I find anything that contradicts it?

- What can I do to confirm this theory?

- Who else in the family can I research to learn more?

That last question is an important one. Faced with a particularly hard-to-solve problem, consider an ancestor’s relatives, in-laws and friends. Records about these folks may name your ancestor or reveal something important about her life. You may find it worthwhile to repeat these eight steps for them. Dig more deeply into their pre-1850s lives, and you may better expose the roots of your own family tree.

Related Reads

From the October/November 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: April 2024