The fife and drums echo through many American families. Whether to confirm a family story, join a patriotic lineage society or satisfy your own curiosity, you may long to know more about your Revolutionary War genealogy.

And if your forebears lived in America between 1775 and 1783, there’s a good chance one of them aided in the struggle for independence: serving in the military, providing funds or supplies, or demonstrating patriotism in a number of other ways. Discovering this part of your heritage can be fascinating and rewarding.

Yet tracing your lineage back seven, eight or more generations—plus finding evidence of your ancestor’s service—can be challenging. Documenting relationships between people who lived two centuries ago takes time and determination.

With the right tools, you can build a research ladder (rung by sturdy rung) that reaches your Revolutionary-era ancestors. We’ll help you determine what types of records to look for, plus how to explore and document your ancestor’s story for future generations.

Getting Started

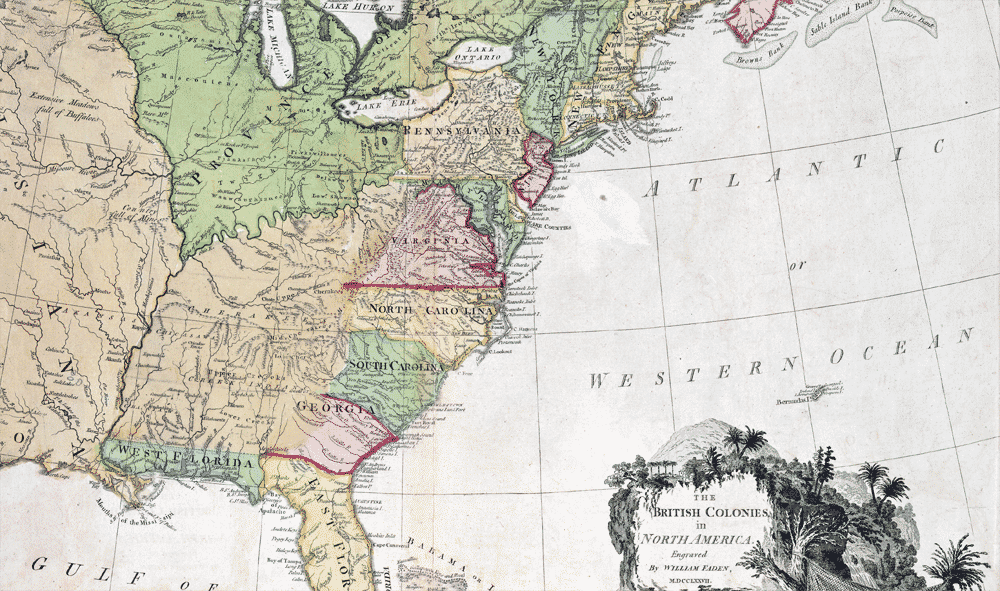

Let’s start with a quick history reminder: The Revolutionary War began in 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord and ended in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris and the withdrawal of British forces. The fight for independence involved all 13 colonies: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts (which included Maine), New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Virginia. Settlers in modern-day Vermont, Louisiana and frontier regions also aided in the struggle.

In many families, however, the legacy of this long-ago period has been lost. If that’s the case in your ancestry, investigate which branches of your family tree will take you back to the 1770s in the United States. (After all, you have 128 fifth-great-grandparents!) Focus your research to lines that have been in the country since Colonial times, then choose one to investigate first.

Examine family stories about Revolutionary ancestors, which may have been passed down in oral or written form. Or maybe a grandparent or cousin was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) or the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), which each require proof of a genealogical lineage to a known patriot. Your goal, then, might be to confirm and document your lineage to that specific person.

Tracing Your Family Tree Back to the Revolutionary Era

As with any genealogical research, begin with yourself and work backward in time, generation by generation, to construct your “ladder.” You’re the first rung, and your parents are the second. If you’re following your mother’s surname, her father is the third. Her father’s father is the fourth, and so on.

As tempting as it might be, don’t try to work down the ladder from a patriot you’ve found online and attempt to make the data fit your family. Unless a close relative has already proven the lineage with the DAR or SAR, you’re likely to encounter a faulty rung and your whole structure could collapse.

For each generation, your goal is to document your ancestor and his or her:

- birth date and place

- spouse’s name (including maiden name)

- marriage date and place

- death date and place

Remember that places are just as important as dates. Make sure you’ve identified the right person and the right county or town. If there are two people by that name in the area, you may need to research both to determine which one is your ancestor.

You’ll also need evidence of the parent/child relationship to link each generation to the one before it. That proof of parentage is the vertical framework that connects the rungs of the ladder. You can’t attach a rung without it.

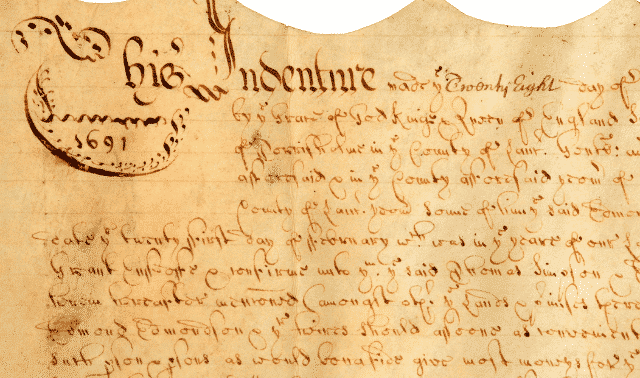

To keep things simple, seek a record that directly states the name, date, place and/or relationship whenever possible. Vital records of birth, marriage and death are ideal. Religious records, such as baptismal registers, are also excellent sources, as are family Bible records from the time period.

Other sources that often provide direct evidence of an event or relationship include census records from 1880 to 1940, wills, probate records and military records. You can use censuses from 1850 to 1870, which name everyone but don’t indicate relationships, to estimate birth years and infer a parent/child kinship.

If none of these records names a parent, consider other sources that might imply a link between generations. Deed records, for example, can indicate kinship when land was inherited. Tax records may show a father and son paying taxes in the same place. Military records might reveal a father served in a militia from the county where his daughter married.

You can find clues even in resources that don’t provide direct documentation. Family histories, pedigree charts and online family trees might outline a path for your search and suggest names and places to explore. County histories can provide hints about where an ancestor came from, and local or state lineage society applications can also be valuable guides.

Identifying Revolutionary War Service

Once you’ve built your ladder back to the Revolutionary War period and have an ancestor rooted in a particular place, the next step is to look for evidence of patriotic service. Service could take many forms. Some men engaged in the fight for independence by:

- serving in a local or state militia

- serving in the Continental Army or Navy

- furnishing a substitute for military service

- assisting allies or defending the frontier

Others took up the mantle of civic duty for new governments by:

- serving as a town, county or state official

- serving in a state or Continental assembly

- joining a committee of safety or similar group

Many more men and women demonstrated their support for American independence by acts of patriotism or sacrifice, such as:

- signing petitions or oaths of allegiance

- providing aid to the wounded

- furnishing supplies or food to troops

- paying special supply taxes

- becoming refugees or prisoners of war

Genealogical Society Records

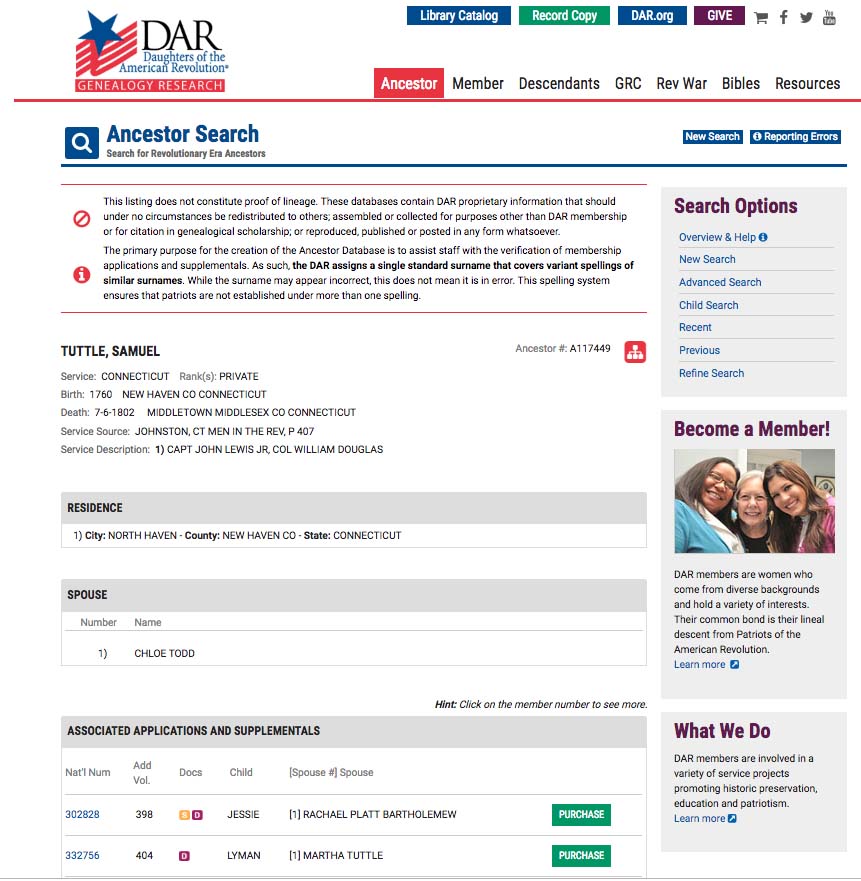

How do you identify people who demonstrated these various types of patriotism? A good place to begin is the Ancestor Search database in the DAR’s Genealogical Research System. This includes all known patriots established by DAR members. Enter your ancestor’s name, plus information about his spouse’s name and/or state of birth, death or service.

If the database includes someone matching your criteria, results will display the personal details and type of service. You can also view a list of the person’s children from whom members have proven lineages. Purchase a copy of a member’s application and supporting documentation (when available) for a nominal fee to give you a helping hand with your research.

Although the SAR doesn’t offer a patriot index, Ancestry has digitized and indexed “Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889–1970.”

It’s important to note, though, that no lineage society has a complete listing of everyone who contributed to the colonists’ efforts. If you don’t find your ancestor’s name in DAR or SAR sources, you’ll need to dig a little deeper to determine whether he or she participated. And regardless of whether or not your ancestor is listed in these databases, you’ll want to fact-check the documented lineages for yourself.

Military Records

Colonial men fought for independence at the local, state and Continental levels. In the process, they may have created service, pension, bounty land or other records. The National Archives’ guide to the American Revolution provides a basic outline of these records.

Service records include rosters, muster rolls, payrolls and more. British forces destroyed many of these during the War of 1812 when they burned Washington, DC, but surviving records were transcribed into compiled military service records for each soldier and sailor. Fold3 has digitized these as part of its Revolutionary War Collection, and FamilySearch has rosters for six states. A collection titled “Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1783,” is online at Ancestry, Fold3 and FamilySearch. Even if service records at the federal level haven’t survived, you might find surviving militia lists or payment records at the state level. Check state archives to see what resources are available.

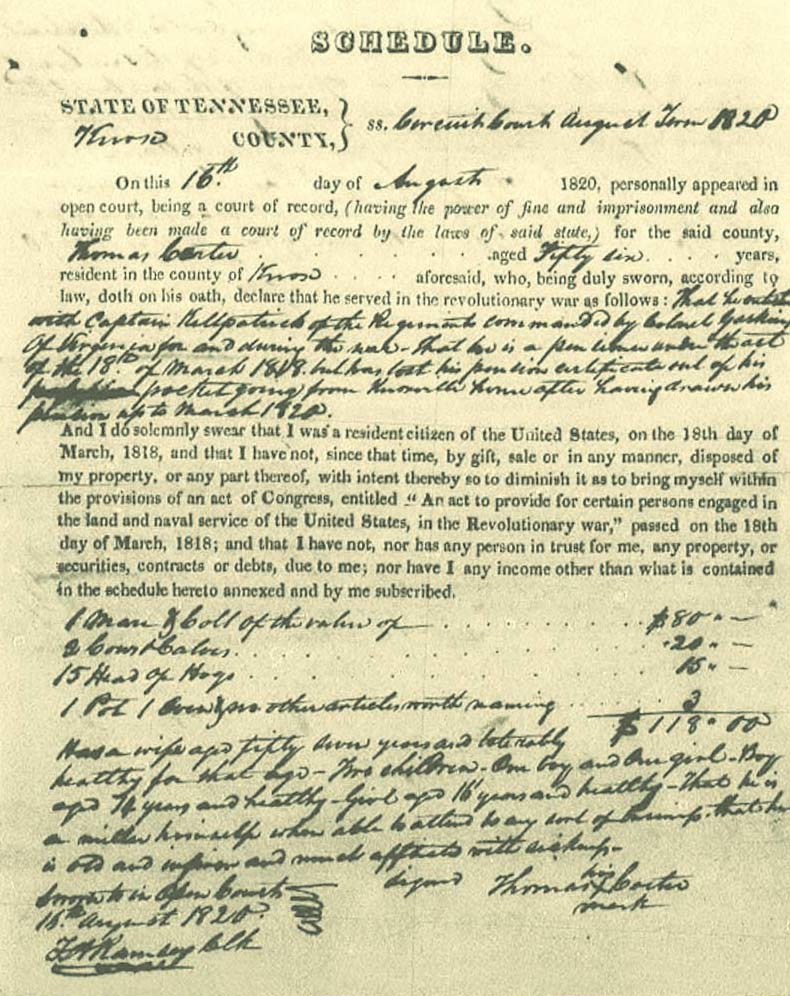

Pension records could exist for soldiers or their widows who lived long enough to see pension laws enacted. FamilySearch, Fold3 and Ancestry all host digitized Revolutionary pension files, and they contain more personal details than service records (and sometimes name heirs). Pension rolls list the names of all those receiving payments in a particular year. Final payment vouchers usually indicate who received monies after a veteran’s death. Find a master search box for Ancestry’s extensive collection of indexed Revolutionary War records.

Bounty land records were created when soldiers or their widows applied for land warrants based on military service. The fledgling US government was land rich but cash poor, so it compensated veterans with public land in frontier areas such as Ohio. Some veterans assigned (sold) their warrants rather than relocating.

Start your search at the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office (GLO) Records. Many bounty land files have been merged with online pension records. However, a large collection of unindexed files is only available in-person at the National Archives.

Other resources that indicate military service include the 1840 US census, which asked the age of Revolutionary War veterans, and indexes to headstone applications and grave registrations. Keep in mind that grave records will be found where the soldier died—not necessarily where he served. Find Revolutionary resources on the FamilySearch Wiki.

Non-Military Sources

Unlike civil service, displays of loyalty and patriotic contributions were not uniformly or widely recorded, and so few large databases compile them.

One national resource is the American State Papers. Click Browse American State Papers, then select Public Lands (eight volumes) or Claims (one volume). Search the index of each volume to see if your ancestor submitted a land or private property claim arising from the Revolutionary War.

The American Genealogical-Biographical Index (AGBI), created by the Godfrey Memorial Library and searchable online, is another place to look for mention of your Revolutionary-era ancestors, including doctors and town officials. The index is a finding-aid to family histories and published records. Look for the original source of the entry in libraries or online.

Most non-military resources, however, were compiled at the town, county or state level. Search for the following records for 1775 to 1783 in the place your ancestor lived:

- supply tax records

- claims or appeals for payment

- oaths of allegiance or fidelity

- committees of safety, correspondence or inspection

- local government officials

If your ancestors hailed from the Northeast, for example, explore the resources of the New England Historic Genealogical Society at American Ancestors. Cyndi’s List has compiled links to a variety of resources in the category “U.S. Military: American Revolution,” or you can search Google for your ancestor’s state plus Revolutionary War records.

Next Steps for Patriot Research

Once you’ve documented your lineage and identified patriotic service for your ancestor, congratulate yourself on a job well done. And if you want to learn more about your family’s experiences, seek out local and state histories to discover what was happening in their time and place.

Read unit and battle histories to understand your soldier’s service. Online sources such as “American Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783” can help. How did the War for Independence affect your family? Did they move as land opened up to settlers after the war?

Consider various options to preserve and share what you’ve found. The Broadway musical “Hamilton” has sparked renewed interest in Colonial history. And people of all ages are eager to learn about their connections to American independence. Perhaps you could write a short biographical sketch about your Revolutionary War ancestor and give it to family members. Or maybe you can publish your research in a blog, submit it to a genealogical society’s newsletter, or publish a family history book.

Joining the DAR or SAR is another excellent way to preserve your work, and offers the added benefit of meeting other people interested in history and genealogy. Visit their websites to find a chapter in your area. And if you’re struggling to document a particular piece of your lineage, members may be able to help.

Most of all: Enjoy your journey into your family’s history during the Revolutionary War—your personal link to the birth of this new nation.

Related Reads

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: July 2025