Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Millions of people in the United States have French Canadian ancestry. French settlements stretched down what is today the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries, and a century-long diaspora of Québécois further spread French-speaking culture throughout the continent.

My grandparents were part of that diaspora, as either immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants. I and other researchers have to learn about the history of Canada, contemporary record systems, and an often-unfamiliar language.

But with time and practice, you can discover the rich history of your French Canadian ancestry. Here are some of the most-important records for finding French Canadian ancestors, and how you can use them.

Historical Background: What is French Canada?

This article covers the history and records of ethnically French settlers who lived in what became the British colony of Canada (i.e., the St. Lawrence River Valley). It does not cover French speakers who lived in other parts of modern Canada, such as Acadia.

Who are those people? History can provide answers. What is now Canada was first colonized by France. “New France” (in French, Nouvelle France) was the collective term for the French colonies in North America, which comprised five principal areas by the early 18th century:

- Acadia: Modern New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island

- Canada: Modern Quebec and Ontario

- Hudson Bay

- Louisiana: Vast territory from the Great Lakes to New Orleans

- Newfoundland

Canada the colony had the largest population in New France, with numerous settlements all along the St. Lawrence River Valley.

In 1763, as a result of the French and Indian War, France surrendered Canada to Great Britain, which administered it as the “Province of Quebec.” (France ceded its claims to its other colonies north of the Great Lakes—Acadia, Newfoundland and territory around Hudson Bay—to Great Britain earlier, in 1713.)

In the 1791 Constitution Act, the Province of Quebec was separated into two:

- Upper Canada, so named because of its being “higher” on the St. Lawrence River and farther away from the ocean

- Lower Canada, so named because of its being on the lower part of the St. Lawrence River, closer to its mouth

The Act of Union 1840 rejoined the “two Canadas” into a single Province of Canada, with only one legislature. Upper Canada became known as Canada West and Lower Canada as Canada East.

With Confederation in 1867, Canada West became the province of Ontario and Canada East once again became Quebec. From that point, “Canada” refers to the whole country, which today is made up of 10 provinces and three territories.

Originally, the term “French Canadian” was limited to the French who lived in what became this colony of Canada. But after Confederation in 1867, some people started using the term for people of French descent in other parts of modern Canada.

1 and 2. Church Registers and Vital Records

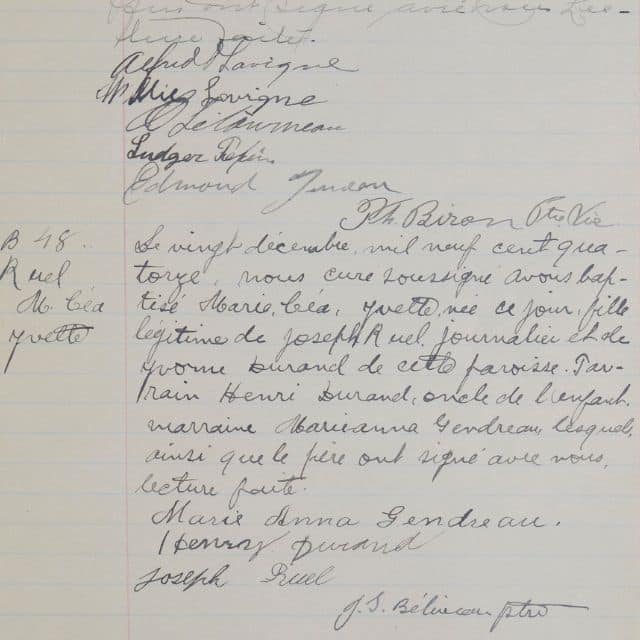

Catholic churches in French North America started recording baptisms, marriages and burials from earliest settlement. The tradition followed from a 1539 royal edict, the Ordinance de Villers-Cotterêts, which granted secular significance to ecclesiastical records. The act also required registers to be kept in the common vernacular (French) rather than the Church’s language (Latin). (The Quebec civil government didn’t begin registering all births until 1926, with a significant overhaul in 1994.)

Early records may have been destroyed by fire, flood or other disaster. But another royal proclamation helped prevent record loss by requiring two copies of all parish registers: one at the parish, and a second at the clerk of the court.

The parish priest would either forward register books to the court for copying once per year, or keep a second, separate copy for the government. Registers are often labeled accordingly: registres paroissiales or registres de la paroisse for the parish copies, or registres d’état civil for the civil/court copies.

In general, parishes still hold the parish copies, while civil copies are held by branches of Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). Registers were also supposed to have accompanying indexes, but not all did.

Some records are subject to privacy restrictions. You can access registers older than 100 years old through BAnQ. The BAnQ website offers free access to images of eligible records that have been scanned, but there is no keyword-searchable index. Other genealogy websites have copies as well, with indexes of varying quality.

Records less than 100 years old are administered by the Directeur de l’état civil (civil registry service), and are only available to certain relatives and legal representatives of those mentioned.

The Program de Recherche en Démographie Historique (PRDH), a collaboration between the University of Montreal and the Quebec provincial government, and the Drouin Institute have been microfilming vital records for decades. Digital copies are available via subscription (either personal or institutional) at Généalogie Quebec and the PRDH site.

3. Census Records

New France first took a census between 1665 and 1666, and it listed all members of the household—not just the head of household—by name. This was the first of several censuses taken during French rule, but most counts survive only in the form of statistical compilations. Much of this information is available through Library and Archives Canada (LAC) or BAnQ.

Census-taking became more-regular in the 18th and 19th centuries under British rule. The heads of household in Lower Canada/Canada West and East (see the sidebar on the next page) were enumerated in 1825, 1831 and 1842, though records don’t survive for all locations.

Decennial censuses began in 1851, and Confederation in 1871 lessened the need for provincial-level censuses. All counts through 1931 are available online, variously from the free LAC, FamilySearch, Ancestry.com and other sites.

4. Land Records: The Seigneurial System

The French brought with them to Canada a feudal form of land ownership that became known as the seigneurial system. In this system, the French Crown officially owned all land, and leased it to administrators in the colony. The administrators, in turn, subdivided it into sections (called seigneuries) and granted them to “seigneurs” (an individual, small group of individuals, or religious group like the Jesuits).

Habitants lived and worked on the seigneur’s land in exchange for payments—either monetary or in the form of livestock or crops—called cens and rentes (rent).

Because most internal travel in Canada was conducted via water, seigneuries valued waterfronts. As a result, lots were drawn long and narrow along shorelines. Seigneurs could clear additional land for settlement as interest expanded, creating a system of sections called rangs. Rangs farther from the shore were less valuable, and were representative of class differences among habitants.

Though Great Britain honored French-era land allotments, English custom (which had a different system and didn’t levy cens and rentes) dictated later land allotment. The seigneurial system was abolished in the mid-19th century, but didn’t fully dissipate until the late 20th century.

Records of land purchases (achats) and sales (ventes) can be found in the notarial records, which we discuss in the next section.

5. Notarial Records

In Canada (as in many countries), notaries have similar responsibilities to contract lawyers, handling all aspects of written agreements. Besides the previously mentioned achat and ventes (land purchase records), a notary may have been involved in the creation of a:

- Accord, contrat, or obligation: General contract between individuals

- Achat: Statement of purchase of real or personal property

- Bail: Lease

- Contrat de marriage: Pre-marriage contract, which established dowery, inheritance rights, and so on

- Donation entre vifs: Receipt of gift made during one’s lifetime in exchange for a privilege, such as being provided for in old age

- Engagement: Labor contract (not a record of betrothal)

- Inventaires après décès: Estate inventory

- Procés Verbal: Written report, usually of a legal proceeding

- Testament: Will

- Tutelle: Guardianship record

- Vente: Statement of sale of real or personal property

Note that some items that (in other countries) might typically appear in a will—such as dower rights and the stipulations about the division of an estate between surviving spouse and children—may have been established in a marriage contract instead. Other arrangements were made through the donation entre vifs mentioned above.

Wills that were created may have been done long before the person’s death, so look for them by date of completion, not by the person’s date of death. Search for agreements and other probate documents both where someone lived and elsewhere, as people sometimes entered into contracts with people in other communities.

Achats and ventes documented purchases or sales of property, respectively. Either record included all terms of the arrangement; whether the transaction generated an achat or vente depended on who registered with the notary. The buyer would have registered an achat, and the seller a vente. There’s no way of knowing which party filed, so it’s best to know the names of both.

Some early notarial records have been indexed and/or abstracted, but there’s no universal index. A number of these were published in book form and are available in libraries.

Tip: Deciphering the French in French Canadian records can be a challenge. Fortunately, the vocabulary used in vital records is relatively formulaic. A simple French-English dictionary should give you enough knowledge to decrypt records. Start with vital records, then move on to more-complicated documents (such as notarial records). Avoid using online translation tools, which are designed for more-modern vocabulary.

Archiv-Histo has been publishing histories and records for more than 40 years. Download lists of Quebec notaries for free from the FAQ section of its website (in French), which show pre-1900 notaries in alphabetical and chronological order, or in order of their last place of practice.

Archiv-Histo projects also contributed to the Parchemin notarial abstracts, a database of indexes published between 1626 and 1800. Parchemin is available only through libraries; there are no individual subscriptions. As of this writing, the New England Historic Genealogical Society is the only institution in the United States that has access, but you can hire researchers to access the database there and send you copies of the abstracts they find.

Ancestry.com is working on a collection of digitized indexes, but (as of July 2025) it is not complete. In addition to searching that collection, review lists of notaries and check their indexes for any mention of documents about your ancestor. Many indexes are available on FamilySearch and BAnQ.

While Ancestry.com has digitized many indexes, far fewer of the actual records are available through them. Instead, many notarial records are available on FamilySearch. From the Catalog, search for the name of the notary.

Note that tutelles and curatelles, as well as many marriage contracts, were removed from the files before filming, so they may not be in digitized records. You can order these, as well as other undigitized documents, from BAnQ. Use the notary’s name to check BAnQ’s catalog to determine which location holds that set of records, and contact that branch. For a record request, you’ll need date, names of parties, and the number of the document.

Bonus: A Guide to French Canadian Names

French settlers often employed the naming traditions of their home country, which differed significantly from those of the English who followed them.

Given names

Individuals were often given multiple personal (“first”) names. Many men were given the name Joseph and women the name Marie, in addition to the name of a godparent and possible additional names. In practice, most were referred to by the name closest to their surname. For example, my maternal grandmother was Marie Céa Yvette Ruel, but she went by “Yvette.” Indeed, the “Marie” was dropped completely and her gravestone reads “Yvette Céa Ruel.”

Dit names

French Canadians also used dit names, which were a kind of nickname or additional surname (dit meaning “called”). These helped differentiate individuals of the same name, but could change seemingly spontaneously. They came from various sources, including:

- Location: La Rivière for someone who lived near a river

- Physical characteristics: LeBrun for a brown-haired person, or LeBlonde for someone with light hair

- Personality traits: Jolicoeur for a happy or friendly person

- Marriage: Adopting a spouse’s or mother’s name, as in the case of my Houde ancestors who adopted the name Clerc from their mother, Jeanne Petitclerc

Surnames

These changed frequently due to the use of dit names. Note that a married woman did not take her husband’s name at marriage, but kept her maiden name throughout her life.

Keep these traditions in mind as you search for ancestors in records, as they may use any combination of given names, dit names and surnames.

Key French Canadian Genealogy Websites

- American-French Genealogical Society (Woonsocket, R.I.): Online collections, large library with many rare or difficult-to-find compilations, local histories, directories, and a magazine (Je Me Souviens)

- Ancestry.com (Lehi, Utah): Census, civil/church records, notarial records

- Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales de Québec (BAnQ; Montreal, Quebec): Early vital records, notarial records, maps, published materials, etc.

- Directeur de l’état civil (Québec, Québec): Vital records fewer than 100 years old

- Genealogy Quebec (Drouin Institute; Longueuil, Quebec): Catholic records (baptisms, marriages, deaths/burials and more)

- Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque at Archives Canada (Ottawa, Ontario): Federal records including censuses, military service documents, maps, plans, records of government agencies, and more

- New England Historic Genealogical Society (Boston, Mass.): Large library with compiled genealogies, general historical information, local histories, archive publications, manuscripts, etc., plus access to the Parchemin notarial index

- Société Généalogique Canadienne-Française (Montreal, Québec): Library with extensive holdings, online collections, and journal (Mémoires de la Société Généalogique Canadienne-Francaise)

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: July 2025