Travelers to Eastern Europe trek to Sighisoara to see the birthplace of Vlad Tepes, better known as Dracula. The house itself is ordinary, bearing only a small plaque in honor of its famous occupant. But when you roam the citadel’s medieval battlements and archaic, cotton candy-colored buildings, it’s easy to understand why Transylvania has inspired so many spooky stories.

Romanians are quick to point out that the vampire lore is fiction — torture tactics aside, Vlad “the Impaler” is revered for his efforts to unite Romania. Yet Transylvanian tourist shops happily capitalize on foreigners’ misconceptions by hawking Dracula merchandise.

Which I, of course, couldn’t resist. Two “I Love Dracula” bumper stickers and a stack of Vlad postcards later, I trekked to the old Saxon cemetery behind Sighisoara’s 16th-century Church on the Hill. Ambling between the overgrown plots, I recalled a conversation with a neighbor back home. She told me her husband had Romanian ancestry — her brother-in-law used to tease her kids that they were descendants of Dracula. She laughed and said the kids ought to look at the photos of my trip to see what their ancestors’ country was really like.

Those photos hint at the rich heritage my neighbor’s family — and the other 4.5 million Americans with Eastern European roots — have to discover. Though nothing compares to seeing the old country firsthand, you can explore much of your ancestry right here in America.

From this side of the Atlantic, Eastern Europe remains mysterious and often misunderstood. Even the term is tough to define: Where does the region begin? Where does it end? For genealogy, it helps to consider historical connections between peoples and cultures. Historians put Slavic peoples into three categories: West Slavs include Czechs, Slovaks and Poles (see the December 2000 Family Tree Magazine for a guide to tracing Polish roots). South Slavs include Bosnians, Croatians, Slovenes, Serbs, Montenegrins, Bulgarians and Macedonians. They’re separated from East Slavs — Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians — by Hungarians (or Magyars), who migrated from central Asia, and Romanians, who descend from the Dacians of the ancient Roman Empire.

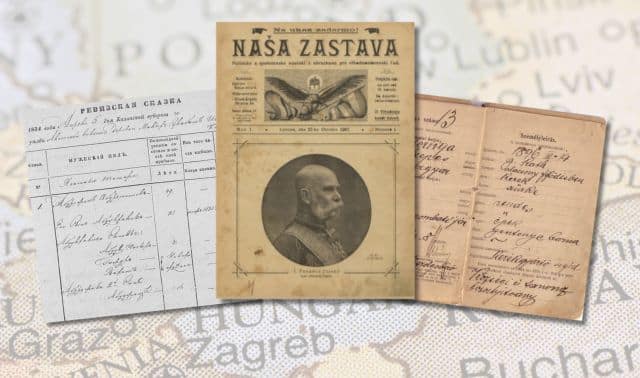

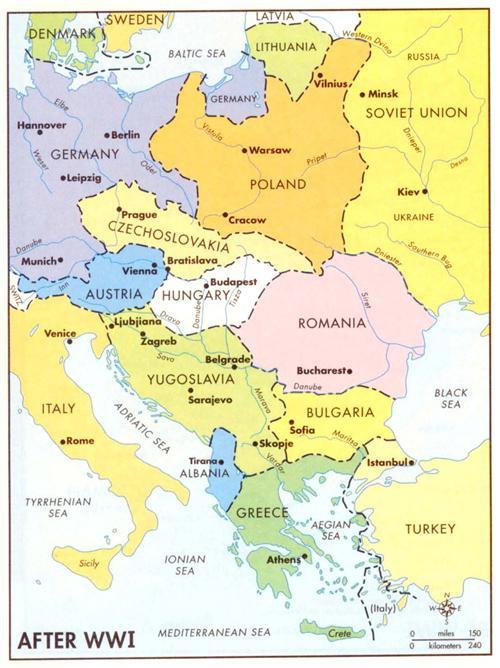

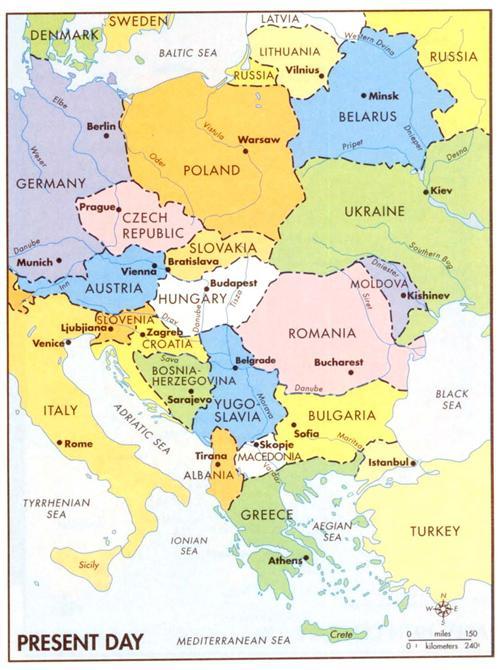

When most Eastern Europeans immigrated to America, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were the region’s dominant powers; East Slavs remained under Russian influence. So here we’ll look at the modern countries carved out of those empires, including the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. (We’ll look at East Slavic and Baltic countries in a future Family Tree Magazine.)

Those expanding empires and changing borders mean tracing your roots here won’t necessarily follow political boundaries. Grandma’s naturalization papers may say she came from Hungary, but her village could now be in Croatia, Slovakia or Romania. You may also discover a distinction between your ancestors’ nationality and ethnicity. Scientist Nikola Tesla, for example, emigrated from Croatia, but his parents were ethnically Serbian. And Carpatho-Rusyns don’t have their own nation — their homeland is in present-day Slovakia, Poland and Ukraine.

Building a network

Before you dive into the complexities of European research, though, you need to thoroughly explore your family history here. Your first step, of course, is gleaning clues from family members. But don’t stop with your closest relatives. “Talk to cousins in different branches of the family — your grandparents’ brothers and sisters,” advises Duncan Gardiner, a professional genealogist who specializes in Czech, Slovak, German and Carpatho-Rusyn research. Great-uncle Marek’s family may have clues you won’t find anywhere else.

Look for distant cousins at online message boards, where you can post queries and search archived messages. Genforum <genforum.genealogy.com> and Ancestry <boards.ancestry.com> have boards for every Eastern European country. The Federation of East European Family History Societies (FEEFHS) has country-specific Research Lists at <www.feefhs.org/index/indexrl.html>. You’ll find more queries and advice in mailing lists — research communities that do lookups, share expertise and work together to beat brick walls.

Look for help offline, too. “The most useful thing a beginner can do is join a society,” says Gardiner. “When you sign up, they usually send you an introductory packet,” which contains materials for getting started. Other perks include newsletters, access to the society’s resources and help from experienced researchers. FEEFHS is an umbrella organization for ethnic- or country-focused groups, and member societies have Web pages on its site. You’ll find a sampling of societies in the Toolkits on the following pages.

Use traditional US sources — censuses, passenger lists, naturalization records — to fill in your family tree back to the immigrant generation. Here, you have an advantage: Most Eastern Europeans immigrated fairly recently, so their US records are likely to contain more detailed data. Through these records, home sources and stories, your goal is to uncover two crucial clues: your immigrant ancestors’ native name and place of origin.

From ship to shore

Part of that process is learning about their countrymen in the United States. Study your ethnic group’s immigration patterns — looking at what others did provides context and can focus your search. For example, few Eastern Europeans came here before the 1800s. Then a mid-19th century potato blight drove nearly 100,000 Czechs to Texas, Missouri and Wisconsin. Croatians and Serbs also came over in the mid-1800s; most were Dalmatian sailors and fishermen who jumped ship (sometimes literally) in New Orleans, settling across the South and in California. A small surge of Hungarian immigration followed the nationalist revolt of 1848.

Your ancestors were far more likely to have been among the flood of Eastern Europeans that poured in near the turn of the century. By this time, the Industrial era was well underway in the West, but Eastern Europe lagged behind. Vestiges of feudalism persisted — Hapsburg lands had abolished serfdom only in 1848 — and societies remained rural and poor. Desperate to escape overpopulation and poverty, people decided to try their luck in America.

This “great wave” of immigration began around 1880, bringing 650,000 Hungarians, most from northern and eastern areas of Hungary, and 250,000 Slovenes, primarily from the southeast. From 1898 to 1908, 322,000 Slovaks made the journey. By 1914, 150,000 Carpatho-Rusyns had arrived. Rusyn scholar Paul Robert Magocsi says, “There was hardly a family in the homeland that didn’t have a relative in the New World.” Many Romanians arriving before 1900 were Jewish (see the April 2001 Family Tree Magazine for a guide to tracing Jewish roots); after that, 85 percent came from Transylvania, Bukovina and the Banat.

During the first decade of the 20th century, immigration from Austria-Hungary peaked, and Balkan people began coming in significant numbers: Croatians from the country’s interior, Orthodox Christian Albanians from the south and Macedonian Bulgarians. (Prior to World War I, 60 percent of Bulgarian immigrants came from Macedonia; they considered themselves ethnically Bulgarian and geographically Macedonian.) Serb immigrants usually left areas outside Serbia proper — such as Vojvodina, a military frontier zone where families fled the Turks.

Illiterate male peasants made up the bulk of these immigrants, finding jobs in coal mines, mills and factories. The nearly 100,000 Bohemians and Moravians who came during the 1880s and ’90s, however, often arrived skilled and literate. And they tended to travel as a family instead of sending one person ahead. Slovenian immigrants, though peasants, also tended to be literate.

Still, the majority of Eastern Europeans were what the Macedonian Bulgarians called gurbetchii or pechalbari — fortune seekers who intended to return after a few years, once they’d earned enough for a better life back home. Some did return — Bulgarian returnees exceeded entrants from 1910 to 1929 — and some became “birds of passage.” For example, a quarter of Slovaks arriving in 1905 had been here before. But many never left America, settling in the industrial centers of the Northeast and Midwest. The biggest Eastern European enclaves formed in and around New York, Chicago, Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

Eastern European immigration slowed at the start of World War I, then virtually halted when the US government passed “quota” laws in 1921 and 1924. These laws limited newcomers based on how many of their countrymen were already here. Eastern Europeans had only been immigrating en masse for a few decades, so they had low quotas. But the laws didn’t deter everyone: Some went to Canada; others entered the United States illegally. After World War II, a smaller influx of intellectuals and artists fled to America to escape communism.

The main port of entry for the great wave of immigrants, of course, was New York. Until 1892, immigrants were processed at Castle Garden; after that they passed through Ellis Island. You now have electronic access to Ellis Island records through the new American Family Immigration History Center <www.ellisisland.org> (see the June 2001 Family Tree Magazine). Or you can access lists on microfilm via the National Archives and Family History Library.

Over the borderline

The next step in your journey to the old country is a history lesson. “Look up your country in the encyclopedia, and read about its history for the 1800s,” suggests Gardiner. You’ll learn what was going on when your ancestors left, and the events leading up to their departure.

Eastern Europe’s recent political shakeups are deeply rooted in its past. For centuries, the common theme for Eastern European peoples was domination by a foreign power. Hungary traditionally held Slovakia, Croatia and Transylvania. Austria’s Hapsburgs ruled the Czech lands (Bohemia and Moravia). Serbia and Bulgaria dominated the Balkans until the arrival of the Ottomans (Turks) in the 14th century — an event that shaped the region’s history for the next five centuries.

The Ottoman Empire swallowed up present-day Romania and the Balkans, and constantly threatened the other powers, Austria and Hungary. Hungary fell to the Turks in 1526 at Mohács, its king died in battle, and the Hapsburgs snagged Hungary’s crown.

Ottoman rule introduced the Balkans to feudalism, which lasted well into the 1800s. (Serbia and Romania didn’t shake off the Turks until 1878, followed by Bulgaria in 1908 and Albania in 1912.) The Hapsburgs already had a feudal system until the 1848 peasant revolts. Then in 1867, Hungary gained autonomy, resulting in the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Austria retained Bohemia, Moravia and Slovenia; Hungary ruled Croatia, Slovakia and Transylvania. This was the political landscape great-wave immigrants left behind.

All that changed after World War I, when a series of treaties carved up defeated Austria-Hungary. As Angus Baxter explains in his book In Search of Your European Roots (Genealogical Publishing Co.), this resulted in huge territory transfers: Romania gained Transylvania, Bukovina and part of the Banat. Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia became Czechoslovakia. Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Dalmatia, Serbia, Slavonia and Slovenia were united as Yugoslavia. The genealogical fallout: Your ancestors’ country of origin may have changed overnight. And the new people in power may have assigned your ancestral village or province a new name.

Where’s Weisskirchen?

Actually, since lands changed hands so often in Eastern Europe, chances are good your ancestral town’s name was different at some point in the past. Many cities have names in multiple languages; for example, Slovakia’s capital, Bratislava, is known as Pozsony in Hungarian and Pressburg in German. In some cases, new rulers altered town names completely. And we know major cities by still different names in English — Praha as Prague, Beograd as Belgrade, Bucuresti as Bucharest.

So how do you figure out just where your ancestors came from? First you need a place name. Gardiner suggests searching naturalization papers, US baptismal records, obits, tombstone inscriptions and cemetery records.

Once you find a name, though, don’t make a beeline for the atlas. You’ll have better luck if you do some additional research first, explains Gardiner: “The spelling you get in various American sources may not be right. Consult a person who’s familiar with spellings in those languages.” Take advantage of your research network — mailing lists, societies, special interest groups (SIGs). Gardiner says some overseas researchers will do town IDs for free.

The best tool to locate your ancestral town is a gazetteer, or index of geographical names. “If a town had different names, that will often be given,” says Gardiner. Use the gazetteer to identify the town’s location and the map you should look at to find it. You can find good gazetteers at major public libraries and the Family History Library (FHL) or its branch Family History Centers. Gardiner suggests using a statistical lexicon, which is based on census data and usually includes the town’s province, its native-language name and index. Try a place search of the FHL catalog <www.familysearch.org> to turn up gazetteers that cover your ancestral country.

Name that tongue

You’ll have plenty of language hurdles besides place names. So start familiarizing yourself with your ancestors’ native tongue — get a good dictionary, and try to find genealogy-specific resources, such as the FamilySearch Word Lists for Czech, Slovak and Hungarian. You’ll also find help online, including dictionaries and services such as e-Transcriptum <www.e-transcriptum.net/eng>, which offers free translations of short genealogy texts.

Eastern European languages present special challenges when dealing with ancestors’ names. To trace your family in the old country successfully, you have to determine their original name. And that’s not always easy, because many immigrants “Americanized” their names after arriving in the United States. This usually happened three ways, as outlined in Daniel Schlyter’s Handbook of Czechoslovak Genealogical Research (Genun, out of print):

• Immigrants translated given and surnames to their American counterparts, such as Frantisek to Frank or Krejci to Taylor.

• They chose a similar-sounding name — Wenzel for Vaclav or Corrister for Korista.

• They Anglicized the spelling so Americans could pronounce it. Kokoska might become Kokoshka, for example.

(Don’t put stock in family stories asserting that Ellis Island immigration officials changed your ancestors’ name — that’s a myth. See <www.ins.usdoj.gov/graphics/aboutins/history/articles/NameEssay.htmb> and the December 2000 Family Tree Magazine for details.)

And be aware that Slavic-name spellings vary in grammatical context. Czech and Slovak surnames, for example, have male and female endings plus adjective and noun forms.

Unfortunately, language hurdles don’t stop with your forebears’ tongue. The region’s barrage of border shifts means records — like town names — were often in the language of whoever was in power. In Austro-Hungarian lands, early records are frequently in Latin. In the Czech Republic, you may also find German; in Slovakia, Hungarian. Or consider the records of Croatia: They’re a mix of Latin, German, Croatian, Hungarian, Slovene and Italian (for coastal areas of Dalmatia and Istria), plus some use the Serbian Cyrillic form. So your Slovak great-great grandma Alzbeta may show up as Erzsébet (Hungarian) or Elisahetha (Latin); Great-grandpa Francisek from Slovenia might show up as Franz (German). Schlyter’s Handbook has a handy table that shows Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, Latin and English versions of given names. See <feefhs.org/slovenia/sidb1/si-names.html> for Slovenian names and English equivalents.

Learning about naming customs will help you sort through the Franciseks and the Franzes. In Eastern Europe, it was common to name children after a saint whose feast day was close to their birthday. Branka Lapajne, author of Researching Your Slovenian Ancestors, adds that in Slovenia, “it was almost a must for each family to have a Joseph, John and Mary.” Note that Hungarians write their surname before their given name.

You’ll find lists of common names for every area of Eastern Europe at <www.flick.com/onomastikon/Europe-Eastem>. You can also check surname spellings by looking in the country’s online telephone book.

Going to church

You have a name. You have a place. Now where do you get the records you need to trace your family in the old country?

Gardiner says a big mistake Eastern European genealogists make is assuming the records no longer exist. “In my experience, very few have been destroyed,” he explains. “Always have [finding records] as a goal.”

Parish registers will be the backbone of your overseas research. The Council of Trent gave churches the responsibility of recording births, marriages and deaths in the 16th century, but the dates for vital records in your country will vary. Here’s a quick look at church records across the region:

• HUNGARY: Baptisms (keresztelo), marriages (házasság) and burials (temetés) span from the early 1700s to 1895, when civil registration began. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) has filmed registers (anyakonyv) up to 1895, and they’re available through the FHL and FHCs. These films also cover places in Romania and Yugoslavia.

• SLOVAKIA: The LDS has filmed almost all vital records (matriky), with roughly the same dates as Hungary’s. You’ll find Slovak matriky for both Protestant and Catholic parishes.

• CZECH REPUBLIC: The earliest existing Catholic matriky are for the late 1500s, but most priests didn’t comply until the 1600s. From 1620 to 1781, Austria allowed only Catholicism, so Czech Protestants’ matriky were kept by Catholic priests. Czechoslovakia started civil registration for non-churchgoers in 1918, but the state didn’t take over vital records until 1950.

• CROATIA: The FHL has microfilm of Catholic, Orthodox and Greek Catholic parish registers from roughly the late 1500s to 1940s. Civil registration began in 1946.

• SLOVENIA: One parish has records as early as 1458, but that’s an exception — most go back to the 1600s. Civil registration began in 1926. LDS has microfilmed some church and civil registers. Lapajne advises writing to the local archbishopric in Slovenia for records.

• BULGARIA: Bulgarian Orthodox parishes have registers to about 1800. Microfilmed FHL records cover the Sofia, Panagurska and Pazardijk districts from 1893 to 1910.

• ROMANIA: Government vital records began earlier than elsewhere in Eastern Europe, in 1865. For the previous three decades, Romanian Orthodox priests carried out civil registration. After 100 years, churches transfer vital records to the district (judet) archive.

• YUGOSLAVIA: Not surprisingly, with the recent unrest in the former Yugoslavia, the availability of records is murky. Pre-1946 parish registers are kept in local churches — Orthodox, Catholic, Muslim. For areas formerly under Ottoman control, the Turkish government may have records of your family (also true for Romania and Bulgaria).

Archiving your ancestors

You may have luck with other types of records. For example, Hungary’s 1828 tax census, which lists heads of household, is on microfilm. Austria-Hungary took a census in 1869; Zemplén County, Hungary, has been filmed, and “bits and pieces of other areas are in different archives,” says Gardiner.

In Search of Your European Roots is an excellent reference for finding records. You’ll find additional resources on these pages.

In some countries, writing to archives is your best strategy for getting records. Kahlile Mehr, an FHL collection development specialist, says the Czech Republic, Romania and Yugoslavia have been unreceptive to LDS microfilming efforts, so you won’t have the bounty of microfilm your Hungarian and Slovak peers do. Gardiner says Romanian and Yugoslav archives “have not been very responsive,” but the Czech Republic has a system for research requests. You fill out a form (see page 43) specifying your inquiry and a cost limit, then send to the national archives. Expect to wait up to six months for a reply.

Another option is to hire someone to do research for you — either a US-based researcher or one in your ancestral country. FEEFHS maintains a directory of professional genealogists at <www.feefhs.org/frg/frg-pg.html>.

Eventually, you might want to explore medieval villages and ancestral cemeteries yourself. If you plan to use a trip to the old country to further your research, exhaust all your avenues here first. “Identify the town a year ahead of time,” advises Gardiner. “Don’t call the archives a week before and say, ‘I’d like to look at such and such record.’”

And take Uncle Frank’s stories with a grain of salt — leave the stakes and garlic at home.

From the February 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine