Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Navigating the ropes of finding your Italian ancestors can be tricky, but those of us who’ve been tracing our Italian roots since the Dark Ages, long before the word online existed, have managed just fine. In fact, I traced my DeBartolo and Vallarelli lines back to the mid-1700s without leaving US shores and without the aid of a computer. If I can do it, you can, too—following these four key steps.

Numero Uno: Research Names

If you know the town where your ancestors originated, you’re one step ahead to connecting your immigrant ancestor to his forebears in Italy. But sound genealogical research means starting with the present and working back one generation at a time. So first, gather all the identifying information you can in US sources. After all, you don’t want to be tracing the wrong Antonio DeLeo in Italian records. Plus, your ancestor’s name may be different in America from what it was in Italy: an immigrant I’ve helped research named Frank Miller was born Francesco Mollo. Ask family members if they know your immigrant ancestor’s Italian name. In US census records (online FamilySearch.org at subscription sites such as Ancestry.com and MyHeritage.com) search first for the American name. If you get no results, try the Italian name.

Numero Due: Search Passenger Lists

Next, move on to other US genealogical records such as births, marriages and deaths, again checking under both the American and Italian names.

Once you have a good idea of your ancestor’s original name, you’re ready to search passenger lists. These lists, created at the port of departure, are online at Ancestry.com, as well as on microfilm at many large libraries. New York arrival lists are free at CastleGarden.org (1820 until the 1890s) and EllisIsland.org (1892 to 1924). Married Italian women usually used their maiden names when they traveled. My great-grandmother Angelina Ebetino, who was married when she immigrated in 1910 with her small children, was on the arrival list of the Verona as Angelina Vallarelli, her maiden name. But her children were listed with the surname Ebetino.

Francesco Mollo (later known as Frank Miller), age 30, sailed on the Nord America, arriving in New York Oct. 1, 1903. The list shows him as a married male whose occupation was “peasant.” His last residence was “Rogiano.” If you don’t know where in Italy your ancestor came from, the passenger list might be your ticket back to the old country. If your ancestor became a US citizen after 1906, the town of origin should be recorded on his naturalization record. See our Family Tree Magazine article for help using naturalization records.

Especially important to note on the passenger list is the column “Whether ever before in the United States; and if so, when and where?” Many Italians were “birds of passage,” sailing back and forth between Italy and America one or more times before finally bringing their families to the United States. Frank, for example, had lived in Philadelphia from 1896 to 1901. That means there’s another passenger list to look for, the 1900 census to check.

Numero Tre: Find Your Ancestral Hometown

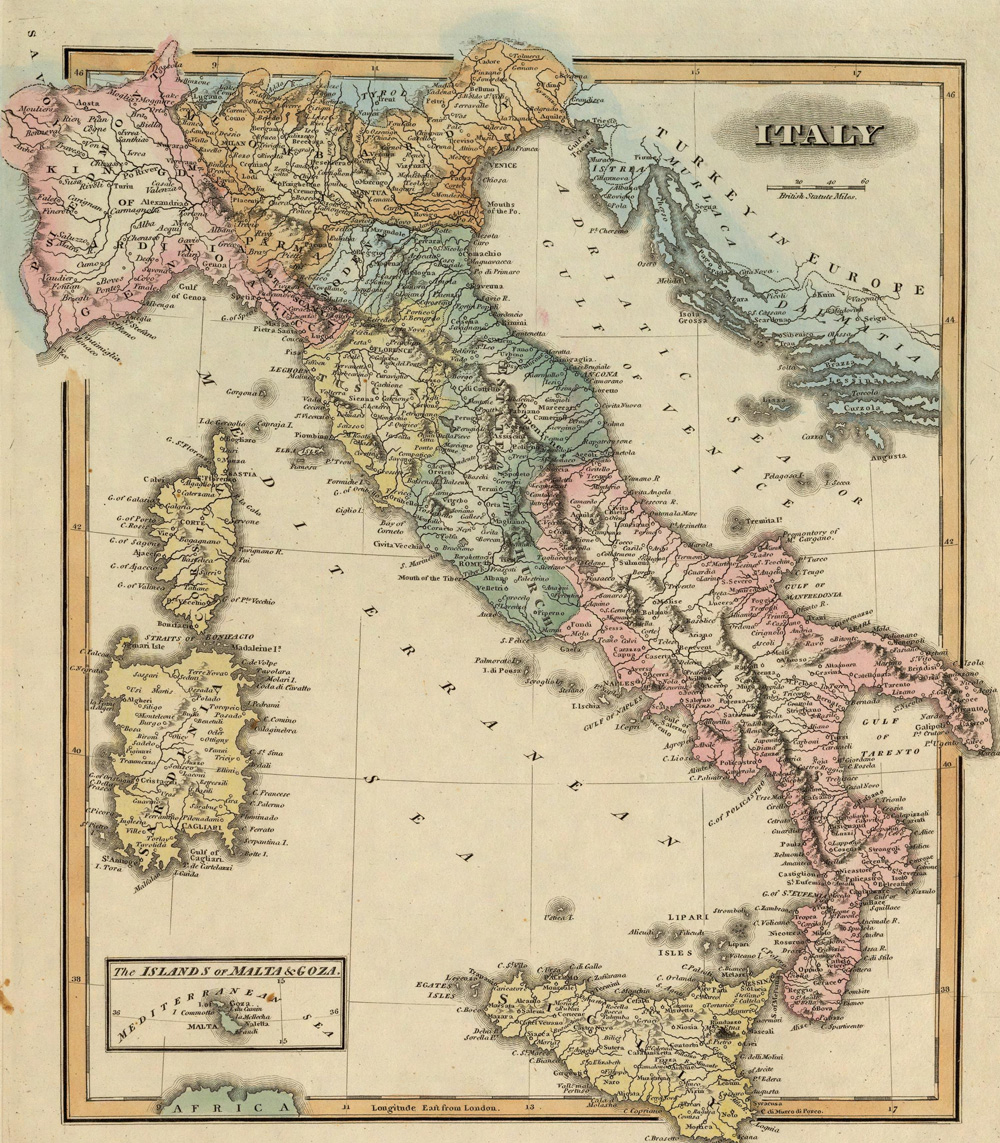

Once you’ve exhausted the potential records America has to offer on your ancestor and learned his Italian hometown, it’s time to cross the Atlantic. The Mollo family knew that “Rogiano” was actually Roggiano Gravina in the province of Cosenza and the region of Calabria. But if you’re not sure of the spelling or full name of the town, run a Google search to find alternate spellings. Or try an online gazetteer, such as the Directory of Cities, Towns, and Regions in Italy. Next, check Comuni Italiani for details such as the town’s province and region.

Numero Quattro: Check Italian Records

Armed with the name of the town, province and region, check the online catalog at FamilySearch to see what Italian records are available. Run a place search on the town name and Italy. Most FamilySearch Italian holdings are civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths, originally kept in town halls across Italy. Records from Roggiano Gravina include registri dello stato civile (civil registers) from 1809 to 1910.

The family believed Frank was born Aug. 18, 1873, so the 1873 volume was a logical place to start. Sure enough, Francesco Mollo was born that date. He was the son of Vincenzo Mollo and Maria Raffaella Aita, and the grandson of Francesco Saverino Mollo (after whom Francesco was named) and Giovanni Aita. The beauty of Italian records is that they typically name three generations.

These records are in Italian, but they’re not all that difficult to use once you get the hang of it. Use the FamilySearch research guides and word lists recommended on the opposite page. Typically, each year had its own volume for births, marriages and deaths, and the volumes are usually indexed. Be aware, however, that the index may be at the beginning or end of the volume. Occasionally, if a supplementary volume was used for that year, the index will be in the middle.

A version of this article originally appeared in the July 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine