You may encounter obstacles in the records such as gaps, ink bleed-through, water damage and sporadic (or absent) indexes. The records for Terlizzi, my family’s village, suffered a worm infestation — their little carcasses and nibbled page corners show up on the microfilm. Don’t expect to find the index in the same place on every film: Sometimes it’s at the beginning of the volume; other times, it’s at the end. And when volumes were divided into two parts because of a large number of births (or whatever), it’s in the middle. To add to the inconsistency, most indexes are arranged alphabetically by last name — but some are organized by first name. Here’s where you really see how popular the names Francesco and Maria were. Another quirk: Some indexes ignore the prefix for names such as DeBartolo or DeFrancesco, so DeBartolo might be grouped with the B’s, and DeFrancesco under the F’s.

The index may record the date of the event, a page number or the record number. If it lists the date, you’ll scroll the film to that date, which is written at the beginning of the record. When there’s just a number, you’ll have to figure out from looking at the records whether it’s a page number or record number. If you don’t find your ancestor in the index, search the records page by page. Usually, the name is easy to spot — often it will appear in the margin. If you don’t read Italian, how can you decipher what the records say? Arm yourself with:

• an Italian-English translation dictionary

• A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Italian Ancestors, which includes word lists, Italian record examples with English translations, and handwriting samples to help you decipher the documents you find

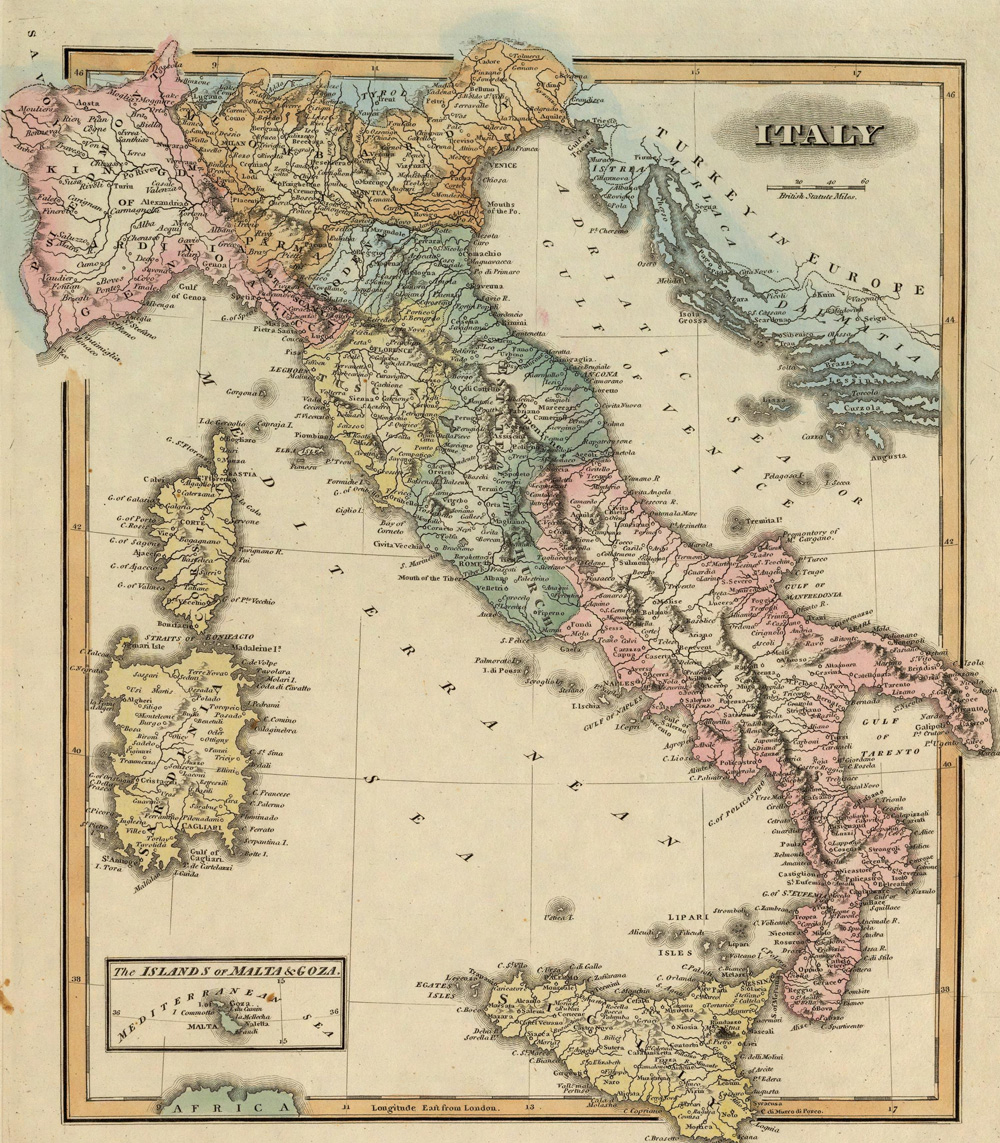

• the FHL’s Research Outline for Italy, available from its Web site (click Research Helps, followed by the letter I. Scroll down to Italy, and you’ll see a series of helpful guides, including the Italy Research Outline, word lists and maps.)

You’ll have an easier time interpreting if you memorize numbers (uno, due, tre, quattro, cìnque, sèi, sètte, òtto, nòve, dièci and so on) and ordinals (such as primo, secóndo, tèrzo, quarto), the names of the months (gennaio, febbraio, marzo, aprile, màggio, giugno, lùglio, agosto, settèmbre, ottobre, novèmbre, dicèmbre — Italians don’t capitalize them) and days of the week (lunedì, martedì, mercoledì, giovedì, venerdì, sàbato, doménica).

Numbers are frequently spelled out — milleottocentosessantotto (1868) — and when numerals are used, 5, 7 and 9 often are difficult to distinguish from one another. Make a photocopy of the first nine records, even if they don’t pertain to your family, so you can use those numbers for comparison with hard-to-read numbers in your records.

Italians abbreviated months, but you’ll find September, October, November and December shortened as 7mber, 8mber, 9mber and Xmber, respectively. (In the ancient calendar, September was the seventh month of the year, October the eighth, and so on.) They wrote dates European style: 4/6/1887 is June 4, 1887. Even names might be abbreviated: Ma for Maria, Anto for Antonio, and Franco for Francesco.

Watch for a little word that means a lot. If you see fu preceding a name, it means the person is deceased. For example, Vito De Bartolo figlio del fu Antonio e di Rosa Veneto means Vito DeBartolo is the son of the late Antonio (DeBartolo) and Rosa Veneto (her maiden or family name). Another key word, found in some marriage records, is maggiora or maggiore, meaning the eldest surviving son or daughter.