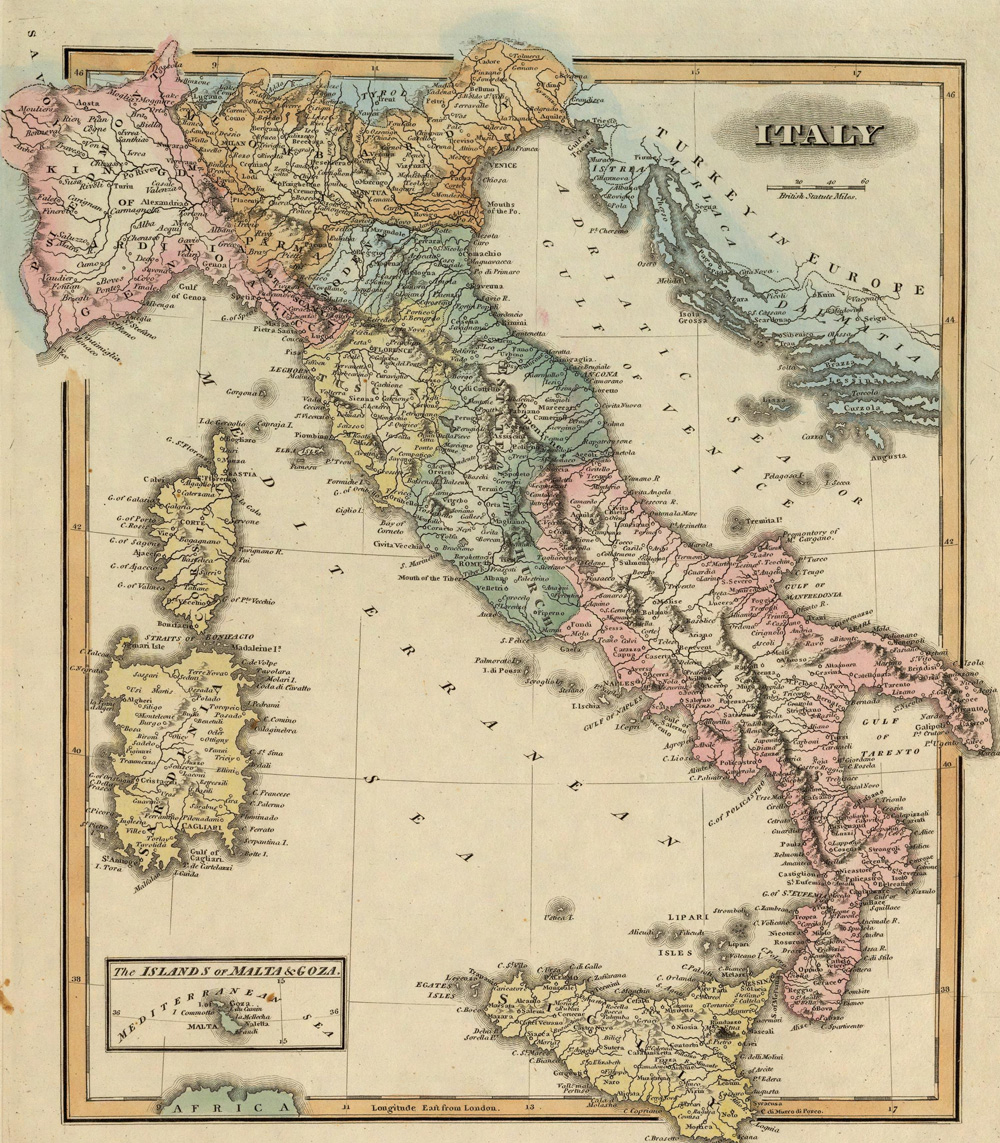

Other Italian records are harder to come by in the United States — you’ll probably need to write to Italy or travel there to use them. If you do, you’ll find that records access varies by town. For example, in Terlizzi (population 2,500), I got carte blanche to go through the civil records and indexes to my heart’s content. Just 15 miles away in Potenza, a city of 100,000, the clerk wouldn’t even let me breathe on the record books. In case you have a similar experience, be prepared with a list of names and dates of the people you’re researching. Then the clerk easily can look up things for you if he’s willing. Most clerks won’t speak English, so know some phrases and questions in Italian.

Italy’s state archives (archivio di stato) have copies of civil records (after 75 years), military-conscription and service records, censuses, tax assessments and notary records. You can research in these archives, or hire someone to do it for you, but the staff won’t do research for you by mail or in person. The Italian Web site <www.db.archivi.beniculturali.it/ucbaweb/indice.html> lists addresses for state archives; so does Nelson’s guide. State archives usually are in each province’s major city, though nine provinces established in 1994 don’t have archives. If your ancestral town is in one of the new provinces, look in that locale’s pre-1994 province. To learn more about researching in Italy, read John Philip Colletta’s Finding Italian Roots.

Here’s a look at other Italian records that could hold clues to your family’s past:

• Census: Italian national censuses taken in 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891 and 1901 list heads of household and merely count up the other members. After 1911, census records (censimenti) list everyone in the household. These censuses, which are kept by the state archives, aren’t microfilmed — nor are they open to the public. But you can write to your ancestor’s town archives to request a census extract — if you can provide enough identifying information about your ancestor. Otherwise, your request will undoubtedly go unanswered. (Be forewarned: Your letter may go unanswered anyway.) Write to the vital-records office in your ancestor’s town.

• Military: One of unified Italy’s first laws mandated military conscription beginning in 1865. At age 18, all men had to report to the draft board and undergo a physical exam. Conscription records (registro di leva) include every man born in Italy from about 1855 (this varies depending on when each area became part of unified Italy). After 75 years, the military turns these records over to state archives, where they’re available for research. The FHL has begun filming military records, so check its catalog periodically by doing place searches of the provinces and towns where the state archives are located.

• Church: The FHL has a few microfilmed church records — if your ancestor’s in them, consider yourself lucky. These documents can take you back generations: For example, some filmed church records for the town of Marco (in Trento) cover 1666 to 1923; Marzano’s (in Parma) span 1575 to 1950. If your ancestor isn’t there, write to his or her parish and hope the priest is in a generous mood that day.

Address your letter to:

Parrochia di [name of church][postal code] [province] Italia

The priest keeps his church’s baptism, marriage and burial records, as well as parish censuses. Even a small town can have several parishes, so look in civil records for clues to which parish your ancestors attended. Always include a donation to the church, even if you visit in person — the more charitable you are, the more likely you’ll get a response. And remember that Catholic Church records will be written in Latin as well as Italian.