Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Between 1881 and 1914, millions of Jews left Eastern Europe to seek religious freedom or economic advancement. They bid farewell to parents, siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins. Through the late 1930s, many of these families exchanged cards, letters and pictures across the ocean. Then, as German occupation spread across Europe, contact ceased.

If you’re tracing your Jewish ancestry, especially if you have deep roots in North America, you may have lost family in the Holocaust and not realize it. When Jewish-American immigrants learned of the Nazi atrocities, many buried their grief and ceased mentioning those who perished. Their children, even if they knew enough to ask, often asked nothing. Their grandchildren, knowing nothing, asked nothing either.

Faded photographs of unfamiliar faces, yellowed letters postmarked from Poland, or chance references in family papers may reveal that relatives did indeed go missing in the Holocaust. And you may doubly despair, first for the loss and then for the belief that you’ll never be able to learn more about these lost lives. But that’s not necessarily the case.

Some records made during the Holocaust survived, and new records were created afterward to document the atrocities. Though these sources may be archived in far-flung heritage museums and Holocaust centers, many are available online. This article refers to both types of records. So it may be possible to piece together—or at least imagine—your relatives’ final days using the following seven resources.

1. JewishGen

JewishGen’s vast, free collection of information makes it a great starting point. First, place your search in historical context with the Timeline of the Holocaust and Frequently Asked Questions. Forgotten Camps describes the 15,000 extermination, concentration and other camps that pockmarked Nazi-held Europe.

Look for Research Divisions (under the Discover tab) focusing on your family’s region of origin, such as Hungary, Bessarabia or Belarus. The groups’ sites offer history, maps, photographs, searchable databases and resource lists. The volunteer-maintained KehilaLinks (formerly called ShtetlLinks) memorialize select towns and villages where Jewish communities once thrived. Websites for communities under Nazi occupation, such as Stropkov, Slovakia, and Lublin, Poland, feature photos, maps, memoirs, local history and links.

If you know a little about the person you’re looking for, search the site’s Holocaust Database (under Research) to scour nearly 200 datasets of survivors and victims. These collections are as diverse as Last Letters from Lódz Ghetto and Jewish Lawyers in Munich.

Also search the Holocaust Global Registry, which holds names of survivors the submitters are seeking. Submitters may be looking for family, friends or even their own identities, in the case of Jewish children hidden from Nazis. You can search for people and places, or browse an A-to-Z list of last names. You also can log in to add a survivor you’re searching for (the HGR FAQ link at the bottom of this registry page offers instructions). In the event of a hit, you can click to contact the submitter of the information.

Other helpful JewishGen databases (accessible under Research>Country & Topical Databases) include the Jewish Family Finder, with thousands of indexed, cross-referenced ancestor names in 18,000 towns. The Family Tree of the Jewish People, a searchable collection of Jewish researchers’ family trees built in partnership with Israel-based MyHeritage, connects those researching the same family branches.

JewishGen has partnered with Ancestry.com to make its historical records searchable on the Ancestry.com website for free. Once you know the names of those you’re searching for, search for displaced person, refugee, postwar emigration and other records. Ancestry.com’s sophisticated search engine may make the records you need easier to find here than on JewishGen.

2. Yizkor Books

Yizkor books are memorial books created to commemorate Jewish communities destroyed in the Holocaust. Each volume, whether penned singly or in collaboration by relatives, survivors, descendants or family researchers, is a world unto itself. It may include a community history illustrated with sketches, hand-drawn maps and photographs of landmarks. Some memorialize town rabbis, lauding their piety, modesty and the miracles they wrought. Some feature essays describing colorful characters, holiday celebrations and day-to-day life. Some include photos (identified or not) of commonfolk like homemakers, schoolchildren, farmers and merchants. Yizkors may include copies of official documents like census records, Jewish fiscal accounts and Holocaust-era transport lists, as well.

When Arthur Kurzweil, author of From Generation to Generation: How to Trace Your Jewish Genealogy and Family History (Jossey-Bass), studied the Dobromil, Ukraine, yizkor, for example, he was amazed that “there was Dobromil, it did have dirt roads and little houses.” When he chanced on a photo of his great-grandfather, he was overwhelmed.

Most yizkors also describe the antisemitism, persecutions and restrictions that led to the destruction of their communities. Stories of survival, such as hiding in haylofts or beneath floors, may follow, as well as survivor accounts of postwar efforts to resume lives.

Many yizkors feature alphabetical or family-by-family necrologies. Because names faded with time, descriptions like infant, grandmother or twin sons aren’t uncommon. Black-framed death notices—in effect, virtual burial plots—may list close family as well as maiden aunts, in-laws, distant cousins and any other relatives the submitter remembers who perished. These may reveal maiden names, otherwise-unrecorded newborns and wider family connections.

Yizkors are commemorative, not archival, so they may not be easy reads. Many were pieced together by committee in folksy Yiddish, Hebrew or other tongues. Moreover, because these volumes are rarely indexed, you’ll probably need to scour them line by line and image by image for genealogical clues.

Check the contributors’ names, too. Their alternately spelled or Hebraized surnames may lead to “lost” family branches. Reference to cousins who left for America, Prague or Budapest may reveal migration patterns. Unidentified photos could show family resemblances, while copies in your family album may solidify genealogical connections. And contributors or publishing committees may hold additional unpublished material, know of others with identical surnames, or have experiences to share.

According to Where We Once Walked: A Guide to the Jewish Communities Destroyed in the Holocaust by Gary Mokotoff and Sallyann Sack with Alexander Sharon (Avotaynu), Jews were scattered in nearly 24,000 communities across Europe prior to World War II. Yet due to the difficulty of managing a yizkor project—or because so many Jewish communities were wiped from the earth, with no survivors to tell of them—few yizkors exist. Additionally, most were privately printed in limited quantities for select groups, making them exceedingly rare.

You can access many yizkor books online: JewishGen’s Yizkor Book Project Database lists all known yizkors by location, links to those translated on JewishGen, and indicates libraries and archives worldwide with substantial collections. When looking for yizkors for your ancestors’ towns, be aware that Jews in villages and hamlets usually shared the same fate as those in larger nearby towns. So they may also share the same yizkors.

JewishGen also offers a Yizkor Book Necrology Database, which indexes victims’ names appearing in its translated texts, and a Yizkor Book Master Name Index, which indexes all persons mentioned in the site’s translated texts.

The JewishGen pages can help you find archival and retail sources of yizkor books, as well as translators who can help you read them. The Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass., offers copies of select yizkors for a reasonable price. The Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library offers free, digitized images of 650 of its 700 yizkor books. Some have been translated into English. The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Library of Congress hold yizkor books you must access in person.

3. US Holocaust Memorial Museum

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum holds materials acquired from private and state archives in dozens of countries and languages. Its files, some recently discovered after being forgotten in the 1940s, document roundups and transports of Jewish citizens, concentration camps, Jewish ghettos and the experiences of survivors. The museum’s library holds hundreds of yizkor books in its extensive Holocaust collection.

With Ancestry.com, the museum created the World Memory Project to encourage volunteers to index digitized Holocaust records including Jews’ ID cards, applications for postwar aid, lists of ghetto inhabitants and more. The resulting indexes are free to search at Ancestry.com; record images are available with an Ancestry.com subscription or from the USHMM.

The museum also documents life during the Holocaust through films, photos, manuscripts, artifacts and oral histories. These are cataloged in the museum’s online Collections Search (under Menu>Collections), though you’ll need to access most items in person. Scroll down on the home page to access a timeline, Holocaust Encyclopedia, maps and a research guide.

Under Learn about the Holocaust, you’ll find the Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center. Its searchable survivors and victims database centralizes information from its collections. You also can browse photographs from the poignant Remember Me? Project, an effort to identify Jewish children displaced by the war. The center also preserves survivor testimonies, maintains the Benjamin and Vladka Meed Registry of Holocaust Survivors (not searchable online) and offers free reference services.

4. Yad Vashem

Located in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem is the world center for Holocaust research and commemoration. Its Hall of Names, a memorial to those who died in the Shoah (Hebrew for “Holocaust”) contains nearly 3 million Pages of Testimony submitted by survivors, friends and family. These record individuals’ names, biographical details, sometimes photographs and submitters’ information. Today, these details are part of Yad Vashem’s searchable Shoah Names Database (accessible under the Digital Collections menu), which memorializes an estimated 4.5 million of the 6 million Jewish Holocaust victims. The names include those from personal papers and documents such as deportation and ghetto records.

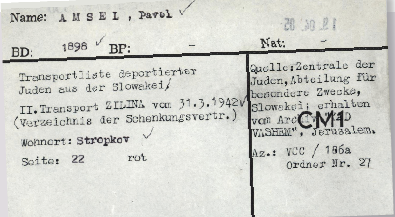

A separate Shoah Deportation Database documents the transport of Jews from their homes to ghettoes or camps, and between camps, with data from historical research, records, legal material, survivors’ testimonies and memoirs. You can search by transport with details such as departure date or places of departure or arrival (in the local language), or by the transported person’s name, date of birth or place.

Search the Righteous Among the Nations Database (under Digital Collections) for information on Holocaust rescuers and those they helped, including children who survived by adopting false identities. The online photo archive, sourced from archives and private collections, is a visual testament to Jewish life before, during and after the Holocaust.

Yad Vashem’s library holds more than 125,000 titles in 54 languages, much of which isn’t online. You can search the documents archive (also under Digital Collections) to find relevant record groups by topic, geographical area and creator. It catalogs transport lists, personal papers, lists of partisans (fighters in the Jewish resistance), post-Holocaust survivor testimonies and other sources from towns, ghettos, work camps and extermination camps across Europe. Once you find material in these catalogs, you can request photocopies for a fee by fax, postal mail or email.

5. International Tracing Service

Since the 1950s, the Arolsen Archives, formerly the International Tracing Service archive (ITS), located in Bad Arolsen, Germany, has researched and documented the fates of millions of Jews and non-Jews who suffered persecution during the Holocaust. The organization provides documentation to survivors and their family members, clarifies the fates of victims, and assists in reuniting separated families.

You can search portions of the ITS’ massive Central Name Index on the aforementioned Yad Vashem website (as well as other designated archives). ITS documents, though, aren’t available online; you must request them or visit in person. Visit the Information for relatives of victims of Nazi persecution page for instructions to request information about specific individuals, at no cost. You must provide the person’s name, place of birth or location before the war, and approximate age. Note that a response may take months. US residents may receive quicker responses through the American Red Cross Holocaust and War Crimes Tracing and Information Center or the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, which manages ITS in the United States.

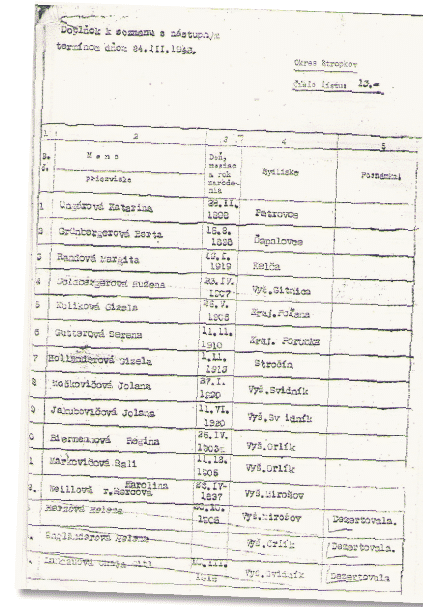

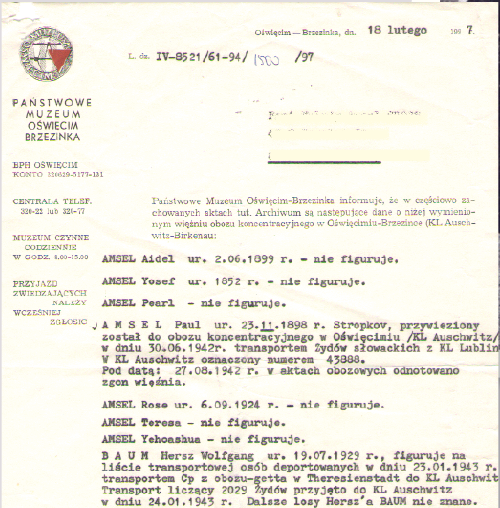

6. Transport and Camp Records

Carefully study any transport lists you find, comparing them with camp arrival records. Not all “pieces,” as Jews were called, actually boarded the transports. Some failed to answer their summons or escaped, while others were added or spared at the last minute. Nor did all on board arrive at camps alive. Many en route succumbed to hunger, thirst, weather extremes, disease and despair.

Though many surviving records from concentration camps have yet to be centralized, they may be available through one of the archives already mentioned or at a museum dedicated to the camp. Keep in mind that inmates were sometimes transported from camp to camp. Try searching online for the camp name and looking for links to archival material, for example:

- Auschwitz-Birkenau: Though nearly a million Jews died at this camp in Poland, no complete list of victims exists. Moreover, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum’s Auschwitz Prisoners database represents only a portion of the museum’s repository. Spellings of prisoners’ names often vary from one document set to another. Entries from transport lists, prisoner registration cards, infirmary records, morgue records and death books may reveal prisoner’s tattoo numbers, along with their dates of birth, professions and fate. You can request additional information from the Bureau for Former Prisoners through this site.

- Dachau: The archive at Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site in Germany has a registry of nearly all its 200,000-plus prisoners, as well as survivors’ eyewitness reports. The archive web page links to a form to request a search for an inmate.

- Majdanek: An estimated 150,000 people passed through this camp in Poland. The State Museum at Majdanek has select prisoner data from 1941 through 1944. You can request information following these instructions, stating the person’s name and any other known details.

7. Survivor Records

Though more than a million Jewish children perished during the Holocaust, a few survived ghettoes and concentration camps. Others hid in orphanages, convents, monasteries or with non-Jews. Some, unaccountably, survived on their own.

Many “hidden children” assumed false identities. By war’s end, however, they had lost not only their families, but also their memory of their past. Even today, many hidden children of the Holocaust, now in their later years, still search for their original names and origins. The Missing Identity website invites you to browse their photographs. Perhaps you’ll recognize a face or a story.

After the war, many organizations worldwide aided displaced Jewish survivors. Those included the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, HIAS (originally the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) and the Search Bureau for Missing Relatives (which ceased operations in 2002; its records are with the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem).

Jewish immigrant and survivor associations, whose members originate from common places, may keep survivor lists, letters, photos and memoirs. Look for contact information in yizkor books, through the Canadian Jewish Congress Charities Committee National Archives, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Yad Vashem and Jerusalem’s oft-overlooked Chamber of the Holocaust, which memorializes more than 1,000 communities. You may learn the names of your great-grandparents, but not their fates. Or you may learn the fate of their village, but not their names. You may trace their steps or lose them along the way. You may find family or, unfortunately, you may find nothing. In any case, you have honored their memories.

Finding Records of the Lost

It helps to begin your search for missing European Jewish relatives with pre-Holocaust local records, such as birth, marriage, religious, military, tax, census and land records. Where European Jews lived before the atrocities often determined their fate and can guide your research. In some areas, Jews were incarcerated; in others, they were murdered on the spot. Some hid, fled, joined resistance groups or assumed false identities.

In parts of the Soviet Union, mobile extermination squads called Einsatzgruppen shot entire Jewish communities—often those in crowded ghettoes where Jews were mandated to live—and buried them in mass graves. Arrivals in extermination camps (expressly for killing), such as Sobibor and Treblinka in Poland, were murdered immediately. Jews “selected” for death in German concentration camps (designed for forced labor, prison and other purposes, though many died or were murdered), such as Dachau and Bergen-Belsen, also usually died nameless. The same applies for those worked to death in Hungarian labor camps, which the German-allied regime imposed instead of military service for Jews.

You might believe that no records of the Holocaust exist, and it’s true that the SS (short for Schutzstaffel, a Nazi paramilitary organization) destroyed thousands of documents as the Red Army advanced and it became apparent the Allies would prosecute Nazi war crimes. But some records do survive, and they speak volumes. Rounding up, transporting and imprisoning an entire population in thousands of camps was a massive logistical undertaking, resulting in arrest and transport lists. In the Slovak Republic, a Nazi-controlled state from March 1939 to April 1945, the property of deported Jews was transferred to the government. Therefore, detailed transport lists were carefully crafted, name by name.

Sterbebucher (concentration camp death books) contain what amounts to death certificates of inmates who died in gas chambers and from other causes, particularly in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The SS took photos inside ghettoes and concentration camps, and Allied soldiers photographed liberated camps. Still more records come from witness testimony, personal accounts, family members’ inquiries about missing loved ones, refugee camps and survivors’ efforts to memorialize the lost.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated October 2024.