What do Marie Curie, Bobby Vinton and Pope John Paul II have in common? If you know their original monikers—Maria Sklodowska, Stanley Robert Vintula Jr. and Karol Wojtyla—it’s easy to tell all three had Polish roots.

Nine million Americans share that heritage, making Polish the eighth-largest ancestry in the United States. Poland’s influence on America goes all the way back to the Revolutionary War, when Polish nationalists Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who’d fought unsuccessfully for their homeland’s independence, helped lead Colonial forces to victory.

The many immigrants who followed brought along with them a vibrant culture, including recipes for signature dishes such as kapusta (sauerkraut), golabki (stuffed cabbage) and pierogi (dumplings); ornamental folk dress; and five national dances (Krakowzak, Kulawzak, Mazur, Oberek and Polonez).

Researching your Polish roots can feel like one of those dances: Sometimes you move forward in rhythm, then a few sudden turns can throw off your footwork. But if you follow the five steps outlined here, you’ll glide gracefully through the search process.

Step 1: Cover the basics.

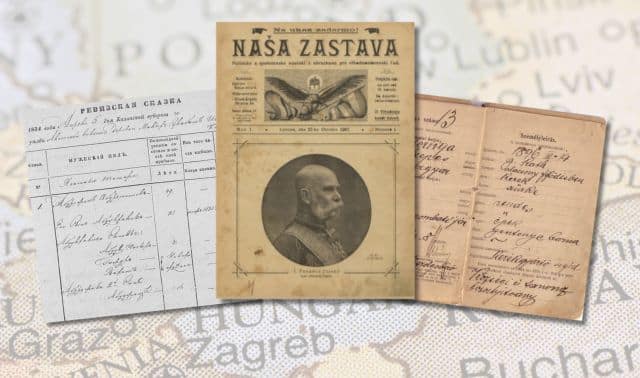

As with any genealogy search, the best place to begin your Polish research is at home. Scour your attic, basement, closets and desk drawers for documents, letters and photographs with family history clues-in particular, you’re looking for certificates, deeds, passports and other items that might contain details such as immigration information (see step 3) and ancestral hometowns (see step 4).

Next, interview your relatives to glean additional facts and family lore. Although oral history is never error-free—people’s memories fade and change over time—it’s an essential source for the names, dates and places you need to start your search. Record family stories in a notebook, and be sure to ask your interviewees if they have any photographs or documents, which can provide additional clues.

Then reach out to the Polish genealogy community for help getting your search on track. Network with fellow researchers on the Ancestry.com Poland message board and read messages posted at Genealogy.com’s Poland page. Join Polish-focused genealogical societies.

Try to hook up with relatives in the old country, too. “Because Polish families tended to be large, it’s inevitable that your immigrant grandmother or great-grandfather left a sibling or two behind when immigrating to America,” says Polish genealogy expert Jonathan D. Shea, a professor of foreign languages at Housatonic Community College in Bridgeport, Conn. Those siblings’ descendant—your distant cousins—could help you fill in the blanks in your family tree. To locate relatives in Poland, search online telephone directories or find a printed telephone book covering your ancestral region (most libraries have them) and write to people with your surname.

Step 2: Learn about Poland’s past.

Polish history stretches back more than 1,000 years. According to legend, Mieszko I founded Poland in 966. It flourished in the 15th and 16th centuries as the Polish Lithuanian Union, a political entity resulting from Queen Jadwiga’s marriage to Wladyslaw II Jagiello of Lithuania in 1386.

In the 1700s, however, Poland’s three powerful neighbors—Austria, Prussia and Russia—carved up the country in the Three Partitions of Poland (1772, 1793 and 1795). Poland as a nation ceased to exist again until 1918, following World War I; it lost its independence once more during World War II, when the Russian and German offenses ravaged southern Poland and nearly 6 million Poles died. Poland was reborn as the Communist People’s Republic of Poland in 1952, and re-entered the global economy in 1990, as the Rzeczpospolita Polska (Republic of Poland).

That turmoil-filled history will color every aspect of your genealogical research, beginning with your family’s arrival in America. The majority of Poles journeyed to the New World during the time Austria, Prussia and Russia ruled their homeland. Immigrants began coming from Prussian-occupied areas in 1848; by the 1880s, the Austrian-governed province of Galicia and the Russian Empire were supplying a steady stream of Polish emigrants.

The influx peaked from 1880 to 1910, during America’s “great wave” of immigration, with an estimated 3 million Poles in the United States by 1910. If your ancestors were among those immigrants, they didn’t officially come from Poland, but from one of those other three nations—a fact to keep in mind as you research in immigration records. Because Poland’s territory shrank over time, it’s also possible your Polish forebears came from an area that’s outside the modern nation’s borders.

Step 3: Determine the immigrant ancestor’s name.

Speaking of immigration, your next step in following your clan back to Poland is retracing your immigrant ancestors’ journey to America. To do that, you’ll need to determine their original Polish names—which may or may not be the same ones they used in America. Like other immigrants, Poles sometimes “translated” their given names to the English equivalents (Jan becomes John; Katarzyna becomes Katherine). With surnames, they most often altered the spelling or pronunciation: Because Polish orthography is so different from English, immigrants wanted to make their names look and sound more American.

Since that generally happened after they arrived in the United States, expect your ancestors to appear in earlier records—including their passenger arrival lists—with their Polish monikers. This is where it helps to understand Polish naming practices. Polish Roman Catholics, for example, would often name a child after a saint whose feast day was celebrated on or near the baby’s date of birth or baptism. Books can help you determine given names in Latin, Polish and German, and find the proper spellings of surnames.

You’ll need to try all the possibilities when looking for your immigrant ancestors’ passenger lists. Luckily, accessing those records is easy: You can search for New York arrivals for free online at The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundations’s Passenger Search (an index and record images cover 1820 to 1957). For other years and ports, Ancestry.com offers paid-access indexes and images of available US passenger lists. Stephen P. Morse’s One-Step Webpages’ search tools for all three sites can help you uncover hard-to-find spelling and name variations.

Alternatively, you can get passenger lists on microfilm at most large public libraries, from the National Archives and its regional research facilities, and from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ FamilySearch website.

Step 4: Find the ancestral home.

This is perhaps the most important step in the research process. To find records from the old country, you need to know where your family lived—just the name of a province or nearby large city isn’t enough, because repositories file records by locality.

“Many American researchers labor under the illusion that an archivist in Poland can tell them where their ancestor was born,” says Shea. “If you don’t have the exact birthplace of your ancestor, you can’t do research in Poland.”

How do you get it? If you listened closely to your relatives and carefully examined family documents, perhaps you noted the name of a city, village or at least a county or district that can serve as starting point for further digging. If none of your home searches turned up any clues, you’ll now need to scour other sources to find out where your family came from. Try vital records, obituaries, cemetery and funeral records, church records, censuses, naturalization papers and the Social Security Death Index (also searchable free through Morse’s website).

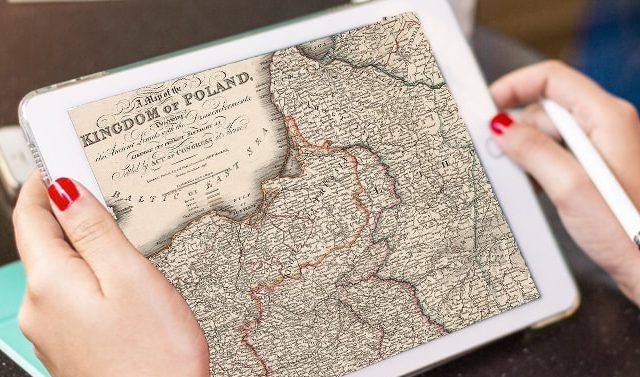

Once you have a specific place name, determine its location—along with pre- and post-WWI government and ecclesiastical jurisdictions—using a selection of maps, atlases and gazetteers. Because of Poland’s turbulent history, administrative jurisdictions have changed numerous times. Historically, powiaty (counties) were the basic geographic division; while those still exist, the government introduced województwa (literally, “voivodeships,” but usually referred to as provinces) in 1975. In 1999, it consolidated Poland’s 49 former województwa into 16. PolandGenWeb’s map can help you sort out that reshuffling. Parish boundaries have shifted overtime, too, and they don’t follow those of political jurisdictions. Gazetteers usually list which jurisdictions a town belonged to.

The FamilySearch Library (FSL) has an extensive collection of microfilmed maps and gazetteers, which you can find by doing a place search of the online catalog for Poland. When you later scour the FSL catalog for Polish records (see step 5), be aware that the library uses place names from the 1968 Spis Miejscowosci Polskiey Rzeczypospilitej Ludowej by J. Jodlowska (Wydawnictwo Komunikacji i Lacznosci). Iwo Pogonowski’s Poland: A Historical Atlas (Hippocrene Books) is also a good reference for resolving geographical questions.

Online, try JewishGen’s Communities search of Eastern European towns, as well as online place-finding tools that focus on particular areas, such as Kartenmeister (Prussia) and Genealogy of Halychyna/Eastern Galicia. You’ll also want to explore the Foundation for East European Family History Studies’ Map Library.

Step 5: Hunt down records.

Now that you know where your ancestors lived, you’re ready to tackle research in Polish records. Luckily, you can get many of the documents you need—including vital records—stateside. As with other European countries, parish records are a staple of Polish genealogical research, as the Polish government didn’t institute civil registration of births, marriages and deaths until 1946.

The FSL’s microfilm collection covers parish registers from Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, Jewish, Lutheran and Orthodox churches throughout Poland, as well as some Prussian civil registrations (1874 to about 1880). To find those records, do a place search of the FSL catalog for your town name—be sure to look under both the Civil Records and Church Records headings. If the microfilm has been digitized, you may be able to view at home or at your local FamilySearch location.

Next, consult other libraries with large Polish collections, such as Central Connecticut State University, the New York Public Library’s Slavic and Baltic Division and the University of Pittsburgh, for materials relating to Polish-Americans’ histories, traditions and communities.

If you discover the records you want haven’t been microfilmed, you’ll need to turn to archives in Poland—by writing for information, hiring a professional genealogist to do research for you or traveling there yourself. Whichever method you select, keep these considerations in mind:

Archives

Records from one registration district could be housed in multiple repositories, including a parish church, archdiocesan archive, local civil-records office or state archive. You’ll want to check all the possibilities, which means getting familiar with Poland’s archive system.

The State Archives of Poland—the country’s national archive in Warsaw—is split into the Archive of New Records for post-1945 materials and the Central Archive of Historical Records for earlier documents. In addition, 30 state archives across the country hold records older than 100 years from their respective regions. Visit Archiwa Państwowe for links to each state archive’s website, where you’ll find contact information and a guide to its holdings.

You can do research by mail; though PolandGenWeb’s research guide cautions that since fees can add up quickly, you should set an upper limit in your request. Your inquiry will have the best chance of meeting with success if it’s concise, specific and written in Polish. The Polish Genealogical Society of America offers tips on writing to Poland for records, and a letter writing guide is available at the FamilySearch Wiki. Or, hire someone who’s fluent in Polish to write the letter for you.

Local civil-records offices (urzedy stanzl cywilnego) are supposed to keep records from the past 100 years, but sometimes you can find older records there. The Polish Genealogical Society of Connecticut and the Northeast has an index to vital records in Polish town halls covering 1880 to 1945; you can request a lookup for a small fee.

Religion

Since clergy served as the primary vital-record-keepers in Poland, knowing your ancestors’ faith can help you root out their records more efficiently. Though Poland has been predominantly Roman Catholic, it also had Europe’s largest Jewish population prior to the Holocaust, as well as Lutherans, Orthodox Christians and Greek Catholics.

Many parishes retain their records, rather than forwarding them to a state or church archival repository, and access is purely at the discretion of the pastors. Besides specifically requesting records, you also might try writing to a priest to find out if anyone in the parish has your surname of interest or might remember your family. Just keep in mind the clergy’s interest in your genealogical pursuits can range from great cooperation to flat refusal.

To track down diocesan archives and their addresses, use the PolishGenWeb Help Pages, Polish Church Archives website and Language & Lineage Press’ database of Parish Affilitzons of Villages in the Former Archdiocese of Wilno by Jonathan D. Shea and Diane Szepanski.

Language

Depending on who was in power where your ancestors lived, their records could be in any of several languages. Records from Russian Poland, for example, were in Polish from 1808 to 1868, then in Russian until Polish independence in 1918. Austrian Poland’s documents were kept primarily in Latin, though you’ll find some Polish- and German-language records. In Prussian Poland, record-keepers used mostly Latin, with some in German and Polish. Read about Catholic record-keeping conventions at PolishGenWeb.

You probably can’t become fluent in all those tongues, but you can get a working knowledge of genealogical vocabulary by referring to our list of basic Polish genealogy terms, studying the FSL’s Polish, German and Latin word lists (available on FamilySearch) and consulting the books in the toolkit. If you’re really ambitious, enroll in a Polish course at a nearby university. You also can contact a Polish genealogical society for a list of translators.

Feeling the rhythm now? Once you’ve found your groove, you’ll see that keeping pace with your Polish ancestors is easier than you imagined.

A version of this article appeared in the May 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated August 2024.