The ground on which their forebears spent centuries is now trod by people of other ethnicities. The actual people who spent their time in these enclaves and left—or fled, depending upon the time period—are nearly all deceased. But the descendants, imbued with a sense of language (complete with dialects), culture and deep affinity for their history, keep a vibrant flame alive amongst the many groups who are collectively called the “Germans outside Germany.”

For many newcomers to genealogy, the first clue is often what shows up in records as a mismatch—either between or within records—such as language and nationality (A typical mismatch might be a US Census that shows native tongue of ancestral immigrant Wilhelmina’s parents as German but their birthplaces as Russia or Romania).

Or it could be the realization that a town of origin for great-great-grandfather Wilhelm can’t be found on modern maps either in Germany or even in the eastern lands that family had known by German-language names but now bear place names in the local language instead. The crux of the matter is that many so-called Germans never lived in a German empire.

Overcoming Brick Walls in German Genealogy Research

Occupants of these places were known by unmistakably German names like Donauschwaben, Karpatendeutsche, Gottscheer and Siebenbürger Sachsen. They retained—in some cases for half a millennium or more—a sense of “German-ness” while surrounded by a variety of other peoples, including Hungarians, Slovenes, Romanians and Ukrainians. Wars (with resulting boundary changes and ethnic reshufflings) as well as voluntary emigration have rendered most of these German enclaves extinct in Central and Eastern Europe, but some groups have created new homes back in Germany or other parts of the world. Their descendants include hundreds of thousands of Americans.

For those who already know they are children of this diaspora (scattering)—as well as those who’ve been brickwalled by “German” ancestors you can’t find in Europe—you might need to fan what’s become a faint flame into one that illuminates your ancestry, perhaps even generations or centuries into these central and eastern European enclaves. Here’s the background to help you do that.

Understanding Migration Patterns Away from Germany

That turmoil of a Germany disunited for centuries helped create enclaves of people who were ethnically German scattered around Europe. Some enclaves—people who truly could be called “pioneers” as the first humans creating towns in an area—date to the heart of the Middle Ages. But others—who were more like “colonists” setting up shop in towns near those of the locals—owe their existence to two great German-speaking empresses of the 1700s, Maria Theresa of Austria and Catherine the Great of Russia.

During her reign from 1740 to 1780, Maria Theresa—daughter of one Holy Roman Emperor, wife of another and mother of two more—heartily encouraged her subjects to emigrate from German-speaking states to the fringes of the Balkan Peninsula, recently won back from the Ottoman Turks. The resulting enclaves were in what are now Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, Poland and Hungary.

Russia’s Catherine the Great populated land also acquired from the Ottoman Empire, and she offered incentives to industrious German-speaking farmers and craftsmen who moved to Ukraine, Bessarabia, Crimea and the Volga River valley.

Once they’d moved to their enclaves, ethnic Germans tended to stay put until economic reasons prompted them to emigrate, in part because the Congress of Vienna redrew European boundaries after Napoleon fell in 1815, and just four entities remained in Eastern Europe: Prussia, Russia, Austria and the Ottomans, in an area where there are now 20 countries.

Early in World War II, the population of what Adolf Hitler called Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans, as opposed to Reichsdeutsche—imperial Germans already living within the Third Reich) was estimated at 10 million; resettlements during WWII were then supplanted by dissolutions as the Russian Red Army swept west and governments eager to eliminate German presence killed or exiled many. For the rest, the diaspora sent them searching the globe for places to live.

How to Find Records of German Ancestors Outside Germany

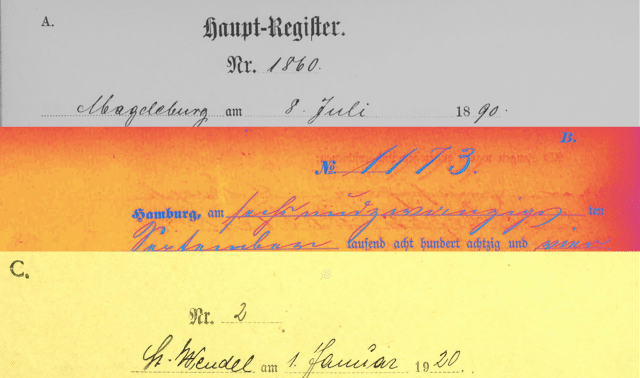

Only sparse records date back far enough to document the medieval pioneers’ migrations. But the colonists who did the bidding of their rulers in the 1700s are often traceable to villages in Germany, since most church records—especially baptism and marriage registers—and records of manumission (release from serfdom for legal emigration) survive. Church burial records from the enclaves may contain references to Western European villages of origin.

FamilySearch, the website of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, is your main source for church and other records. To see if there are records of your ancestral village, use the online catalog to run a place search on the village name; if the name of the village has changed to a local language, you may need to find that first.

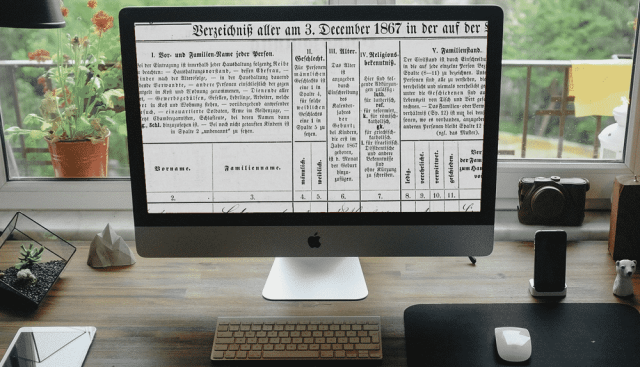

Church records from German enclaves will be in German; civil records will be in the language of the ruling nation, which might have changed one or more times while your ancestors lived there. The FamilySearch word lists are a good resources. Some of the websites you’ll consult are in German, too—Google translate or other such website extension can help.

Not many towns still have old civil records such as birth and marriage certificates, but try contacting a genealogical society covering the area. An FamilySearch catalog lookup on the town name might point you to published indexes and help in ordering from town clerks.

Creative use of the FamilySearch catalog can suggest more resources. For instance, a place search on your ancestor’s country or region might turn up a book with a typically long German title such as Bestandsverzeichnis der Abt. Deutschen Zentralstelle für Genealogie Leipzig im Sächsischen Staatsarchiv Leipzig (Inventory of Holdings of the German Central Office for Genealogy in Leipzig) by Martina Wermes and others. Check the catalog entry and you’ll see this book lists records (including family pedigrees, personal writing and eulogies) of former German settlements in Bessarabia, Bukovina, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Transylvania, the Sudetenland, Slovenia and Southern Tyrol—and it gives German Central Office for Genealogy microfilm holdings for towns in each area.

The Differences Between Donauschwaben and Siebenbürger Sachsen

Besides the large number of “Germans from Russia,” the two largest groups are also good examples of the difference between “pioneers” and “colonists.”

The Siebenbürger Sachsen (Transylvanian Saxons) are the quintessential “pioneer” group, dating to the 1100s, when an invitation from the Hungarian king (then ruler of what’s now northern Romania) to farm and have autonomy to establish their own laws and justice system appealed to migrants from the Rhineland and the Mosel River region as well as the Eifel and Luxembourg.

The area these ethnic Germans settled also goes by Transylvania but don’t confuse them with the nearby Carpathian Germans. Their enclave swelled to some 500 settlements, including the cities Hermannstadt (now called by its Romanian name, Sibiu), Kronstadt (Brasov) and Schäßburg (Sighisoara).

Many Transylvanian Saxons immigrated to America beginning in the 1880s, clustering around steel factories in cities such as Youngstown and Cleveland, Ohio, and Sharon and New Castle, Pennsylvania. All but a few thousand left after World War I, when Romania absorbed the area. An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Americans are their descendants, mostly from 1880s immigration.

FamilySearch has church records for many Transylvanian villages, but most date only from the early 1800s. Collections for some towns cover only registers of Austrian military families. You’ll find a variety of other FamilySearch records, including the Conscriptio Czirakyana feudal land tenancy census of 1819 to 1820. (Run a catalog title search on Conscriptio Czirakyana.)

No distinct group of Germans outside Germany is as large or storied as Donauschwaben (Danubian Swabians), many of whom came from the Swabian region centered around Stuttgart, Württemberg. It’s important to note that the “Swabian” name is a bit of a misnomer, since others were miners and craftsmen from Styria (a province of modern-day Austria), Austrian military, Austrian civilian territorial administrators and office workers, and people from Carpathian areas and the Baden microstate of Durlach.

The Donauschwaben are the epitome of the “colonists,” as they built a number of prominent enclaves along the Danube River—these were areas the Austrian Empire claimed from the declining Ottomans—in what are now Hungary, Romania and Serbia.

The first of this large group to migrate were about 15,000 people to an area known as the Banat, now in southwestern Romania, between 1718 and 1737. Ottoman raids and a bout with bubonic plague killed many of these settlers. The second colonization wave, from 1744 to 1772, consisted of 75,000 people and resulted in German-dominated towns throughout what’s now southern Hungary, Croatia and Serbia in regions called Batschka, Sathmar and Slavonia. A third wave added another 60,000 colonists—including more Protestants than in previous colonization—during the 1780s. Most set out from the German city of Ulm and passed through Vienna and Budapest.

Before World War II, nearly half a million German speakers lived in the Banat alone. After the war, Hungary and Serbia (then part of Yugoslavia) expelled many of them. Meanwhile, 100,000 Donauschwaben left Romania ahead of the Russian army; some who stayed were sent to labor camps in Ukraine and today reside around the world.

Museums and ethnic clubs keep the Donauschwaben memory alive, and you can find numerous records of their journey. They include Ansiedlerakten (settler documents) dating from 1686 to 1855, which occupy 35 rolls of FamilySearch microfilm. These records give settlers’ names, number of children, places of origin and other information recorded as they passed through Vienna. Many of these settlers and their descendants were conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army, so check FamilySearch microfilm of Austrian military records—search the online catalog on the keywords Austrian military.

A Breakdown of Small German Ethnic Groups

Following is an overview of some of the smaller ethnic German groups; we’ve also pointed out important records for each. For additional help and resources, explore the numerous websites, published histories and genealogical societies covering each group.

Deutschbalten (Baltic Germans)

Origin: Throughout Germany

Destination: The Baltic Sea’s eastern shore in three main areas: Estland, roughly the northern half of present-day Estonia; Livland in southern Estonia and northern Latvia; and Kurland (Courland in English), the southern half of present-day Latvia.

Migration history: Baltic Germans were pioneers, settling their new land in the late 1100s. They founded an association of knights that became affiliated with the Teutonic Catholic order in 1236, and eventually morphed into an aristocracy that owned much of the Baltic states. Though Estonia and Latvia became provinces of the Russian Empire in the 1700s, the German-speaking aristocracy remained until after World War I, when the two states regained independence and redistributed their land. Some Deutschbalten left, mainly for America and Germany. Most stayed until 1939, when Estonia and Latvia again fell under Russian rule and nearly all the 70,000-plus German-speaking residents were sent to Poland and, later in the war, to Germany.

Records: FamilySearch has church records of many major towns, including Riga. Most start in the mid-1600s or early 1700s.

Bukovinans

Origin: Swabians came from the southwestern German states of the Palatinate, Württemberg and the Rhineland; Sudeten Germans, from the Bohemian Forest area; and Zipsers, from the district of Zips in what’s now Slovakia.

Destination: Part of Bukovina, in Romania since World War I

Migration history: After Bukovina became an Austrian province in 1775, the government encouraged ethnic Germans to settle there. More Sudeten Germans followed during the early 1800s. A late-19th-century population explosion spurred migration primarily to Canada, but also the United States and Brazil. The Soviet Union and Romania divided Bukovina after World War I, and, in 1940, nearly all the Germans in Bukovina left for Germany proper.

Records: Fortunately, the migrants took along their Roman Catholic and Lutheran church records, which FamilySearch has microfilmed. Some date to original German settlement.

Karpatendeutsche (Carpathian Germans)

Origin: Several areas of Germany—see migration history below

Destination: The northern arc of the Carpathian Mountains (now in Slovakia and subject at the time to Hungary), including four areas: Pressburg (the German name for Bratislava), central Slovakia in the Hauerland, the Zips and the Carpatho-Ukraine (now called Transcarpathia).

Migration history: As early as the 12th century, a Bavarian bishop with extensive landholdings in Tyrol encouraged his subjects from the town of Eisacktal in South Tyrol to populate the village of Eisdorf in the Zips district. Germans who spoke a Bavarian-Franconian dialect went to Hauerland and Pressburg; those from the northwestern Lower Rhineland and Flanders ended up in the Zips.

After 1860, Zipser German peasants and craftsmen immigrated to the United States en masse, most notably to Philadelphia, though more than 150,000 Carpathian Germans still lived in Europe before World War II. The war left 6,000 to 15,000 in Slovakia and 3,000 in Ukraine. Descendants of this group reside mainly in Germany, Austria, the United States and Canada.

Records: Eisdorf and Menhard are among the few villages whose church records can be found on microfilm at FamilySearch.

Gottscheer

Origin: German states of Carinthia, Tyrol, Salzburg, Brixen and Freising

Destination: Gottschee, part of the Austrian duchy of Carniola (now in Slovenia)

Migration history: This group first settled vacant forest land in the 1300s. During World War II, the Nazis relocated them nearby; after the war, the Gottscheer were again expelled to the United States, Germany, Austria, Canada and Australia. Most of the 20,000 to 30,000 Gottscheer and their descendants in America arrived after the expulsions; but some came as early as 1870. Many live in large cities such as New York, Cleveland, Chicago and Milwaukee (and Toronto, Kitchener and Vancouver in Canada) as well as Upper St. Clair Township in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

Records: Roman Catholic church records dating to the 1700s are on microfilm; copies are available through FamilySearch.

Tricks for Finding Your German Ancestors Outside Germany

The advantage to searching for village origins of the Germans from outside Germany is that in many cases they are the most recent of German-speaking immigrants—a substantial number being post-WWII emigrants—and therefore a greater bounty of records is likely to be available.

Although the point has now been reached that nearly all of those who remember the enclaves have passed, that spirit of what once was has not been snuffed out. Many of the first generation beyond the enclaves are still alive and have done oral history with their parents and grandparents. Village history books (often called Ortsippenbücher, plural of Ortsippenbuch) have been published for towns in the former enclaves. Societies focusing on retaining the culture, dress, music and other rich elements of specific enclaves are still around and they, too, preserve the history of the families from these areas.

In cases where you don’t have such specific information, the primary complication will be analyzing the person’s nationality. In census records, the language used by the immigrant or listed for him or her may tip you off: If a Hungarian or Russian spoke German, he likely came from a German enclave. And likewise, finding out an Austrian’s religion may help—most of Austria’s eastern German enclaves were Protestant, while the Germans of the Austrian heartland were almost uniformly Roman Catholic.

FamilySearch often catalogs records by the village name when they were created, which could present a challenge: Eastern European villages often have different names in different languages, and switched names as their rulers changed (or decided to require records be kept in the “state” language). Look for gazetteers and other research aids, such as the Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe‘s historical maps of Poland and northwestern Ukraine.

As with many ethnic groups who have endured a diaspora, the passion of keeping that flame of the “never to be forgotten” home area burning bright is undimmed. Even relatively small groups such as the Gottscheer don’t want to be lumped together with other German groups. And that passion, indeed, likely will be your best opportunity to join the circle of light for the enclave from which your particular ancestry hailed.

German Ethnic Groups Genealogy Websites and Resources

Websites

- Carpathian German Home Page

- Compgen.de’s GenWiki German Genealogy Home Page (Note: Click the Regional tab for links to resources for researching Germans who lived outside Germany.)

- David Dreyer’s Ship Extraction Database (Note: Website has not been updated since 2013, but all information is still relevant.)

- Gottscheer Heritage and Genealogy Association

- JewishGen Communities

Books

- Genealogical Guide to German Ancestors from East Germany and Eastern Europe, English edition, by Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ostdeutscher Familienforscher (Verlag Degener & Co., out of print)

- German Towns in Slovakia and Upper Hungary, 3rd edition, by Duncan Gardiner (self-published, out of print)

- Germanic Genealogy: A Guide to Worldwide Sources and Migration Patterns by Edward R. Brandt, Paula Goblirsch, Ray Kleinow and George E. Arnstein (Germanic Genealogy Society, out of print)

- Österreichisch-Ungarisches Orts-Lexikon (Gazetteer for the Austro-Hungarian Empire) by Hans Mayerhofer (Carl Fromme, out of print): Available on FHL microfilm 1256324.

- Reisehandbuch Siebenbürgen (Travel Handbook of Transylvania) by Heinz Heltmann and Gustav Servatius (Kraft Verlag, out of print): Includes a village index.

- Tracing Romania’s Heterogeneous German Minority from Its Origins to the Diaspora by Jacob Steigerwald (Translation and Interpretation Services, out of print)

- Wandering Volhynians magazine (out of print, but index is available)

Organizations and Archives

- Association of Transylvanian Saxons (Verband der Siebenbürger Sachsen in Deutschland e.V.)

- Bukovina Society of the Americas

- Donauschwaben USA

- Foundation for East European Family History Studies

- Gottscheer Heritage and Genealogy Association

- Homeland Association for Carpathian Germans in Germany (Karpatendeutsche Landsmannschaft)

- Institute for Danube-Swabian History and Regional Studies (Institut für Donauschwabische Geschichte und Landeskunde)

- Saxon State Archives

- Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe

- Working Group of Danube Swabian Genealogists (Arbeitskreis donauschwäbischer Familienforscher e.V.)

- Working Group of Eastern German Genealogists (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ostdeutscher Familienforscher e.V.)

Related Reads

A version of this article originally appeared in the December 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: December 2024

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.